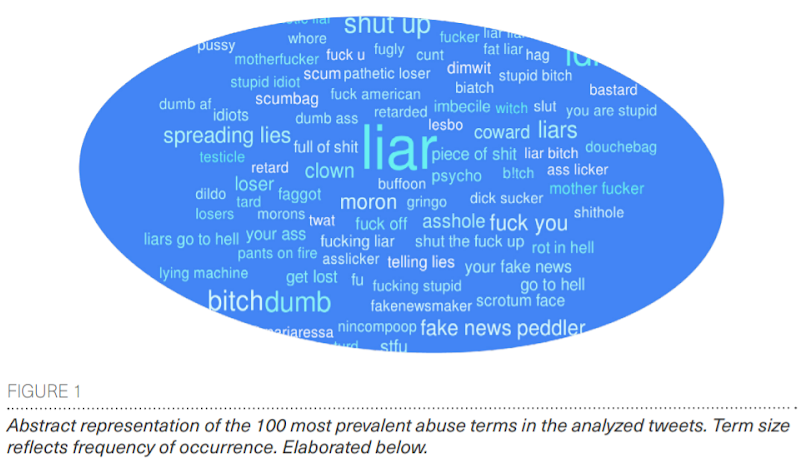

Content warning: This article includes graphic content that illustrates the severity of online violence against women, including references to sexual violence and gendered profanities. This content is not included gratuitously. It is essential to enable the analysis of the types, methods and patterns of attacks against Maria Ressa.

A collaborative analysis of hundreds of thousands of social media posts directed at internationally acclaimed Filipino-American journalist Maria Ressa over the past five years demonstrates what advocates and journalists have long warned: Online violence against journalists — especially women — is a pervasive issue with offline consequences. This digital violence, especially when fueled by the state, puts journalists’ safety at direct risk, and it threatens the news industry’s freedom to act as an effective fourth pillar of democracy.

Researchers Julie Posetti, Diana Maynard and Kalina Bontcheva employed Natural Language Processing — which uses linguistics, computer science and artificial intelligence, in this case to analyze large sets of Facebook and Twitter data — to track the onslaught of online violence against Ressa, and the trajectory of state harassment against her. They collaborated with Ressa’s news organization, Rappler, on data collection and analysis for the study, which will feed a larger UNESCO-commissioned research project.

The report lays bare the sexist, misogynistic, racist and graphic nature of the attacks against Ressa, and shows how incessant, targeted online abuse can create an environment that enables antidemocratic forces to crack down on journalists and their reporting.

[Read more: Online violence, fueled by disinformation and political attacks, deeply harms women journalists]

It’s a “very 21st century storm,” the researchers explain. “It is a furor of disinformation and attacks — one in which credible journalists are subjected to online violence with impunity; where facts wither and democracies teeter.”

Ressa is fighting nine separate legal cases today, which could send her to prison for the rest of her life if she is convicted on all charges — just for reporting dedicated to holding to account her country’s leaders. The legal assault is a direct consequence of an environment made ripe by the targeted online violence.

“The authorities vilify her, and President Duterte has helped to amplify online attacks against her. State authorities thus both directly attack Maria, and also create an enabling environment that facilitates and fuels abuse from others. In turn, online abuse emboldens the authorities in their persecution of her,” said Caoilfhionn Gallagher QC, the co-lead of Ressa’s international legal team. “In my view, there is a symbiotic relationship between the abuse Maria experiences online and the progress of the legal harassment offline.”

Some of the attacks are state-orchestrated, evidence suggests, and they are fueled by demonizing rhetoric from Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, and pro-Duterte bloggers and influencers.

The data likely captures just half of the English-language or blended English-Tagalog vitriol directed Ressa’s way on Facebook and Twitter, the researchers note, due to limitations in the Natural Language Processing technology. It also excludes attacks via Facebook Messenger, which are “the most brutal Ressa has experienced,” according to the report. Much of the public harassment is intentionally subtle, too, in part to elude automated tracking tools.

In all, researchers analyzed nearly 400,000 tweets and more than 57,000 Facebook posts and comments directed at Ressa between 2016 and 2021. Here is a snapshot of some of the findings:

Nature of the attacks

- 60% of the online violence seeks damage to Ressa’s credibility as a journalist, including disinformation-laced attacks and false claims that she trafficks in “fake news.”

- 40% of the attacks are classified as personal. They feature significant sexism, misogyny and explicit language, including attacks on Ressa’s physical appearance and manipulated images of her head with male genitalia. This type of violence also includes threats of rape and murder, and targets Ressa’s skin color and sexuality.

Method of the attacks

- Attacks can be orchestrated, a hallmark of which is deployment of fake and bot accounts. Facebook has at times removed networks of what they term “coordinated inauthentic behavior,” though their response on the whole has been “woefully inadequate,” according to Ressa.

- Facebook is the main facilitator of online violence against Ressa. She says she feels “much safer” on Twitter.

- Attackers use hashtags, memes and manipulated images to increase volume of, and engagement with, their harassment.

- Attackers publish revealing private or personal information — called doxxing — to encourage offline attacks against Ressa.

Attack triggers

- Online violence against Ressa increases following high-profile media appearances she makes, international awards she receives and her court appearances.

- Attacks increase in the aftermath of Rappler’s published investigative reports into the Duterte administration, and in reaction to Ressa’s own reporting and commentary on disinformation and Duterte.

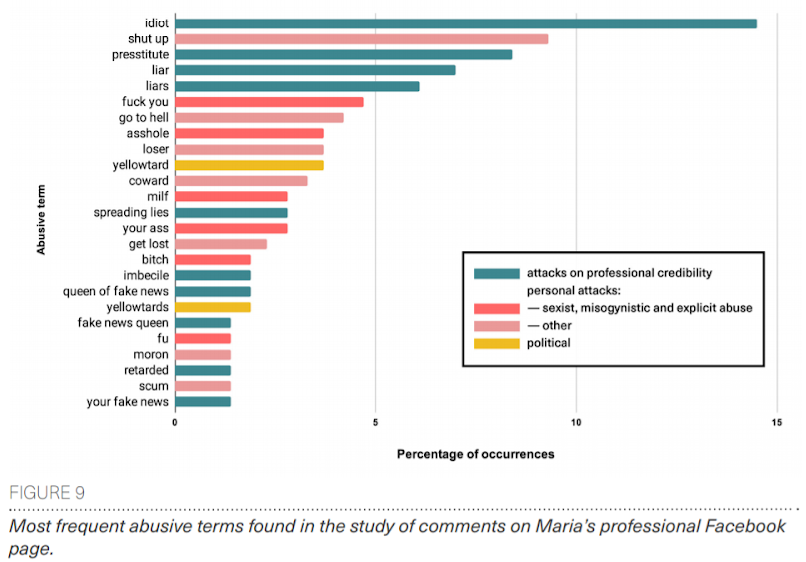

The violence is especially pronounced on her professional Facebook page, where for every positive comment that researchers analyzed, she received 14 abusive attacks against her. One quarter of the more than 9,400 attacks tracked from 2015-2018 on the page targeted her professional credibility, and about 14% were personal in nature. Another 15% were politically themed, accusing Ressa and her journalism as being in opposition to Duterte. Ressa no longer uses the page because of the harassment.

Disinformation is a major feature of the online violence Ressa has experienced, infused in all the different types of attacks against her. Malevolent actors have also coordinated “pile-ons,” or “networked gaslighting” campaigns in which they falsely portray Ressa’s journalism as acts of disinformation.

The disinformation tactics used against Ressa and Rappler fall in line with what a UNESCO-ICFJ survey uncovered: that 41% of the almost 100 women journalists polled said they had experienced online violence which they believed were linked to orchestrated disinformation campaigns.

“This abuse doesn't just discredit Ressa and enable her legal harassment,” the researchers note. “It also serves to further erode public trust in independent journalism, and facts in general, sowing confusion and undermining the democratic pillar of press freedom in the Philippines.”

[Read more: Decoding Filipino-American journalist Maria Ressa's complicated legal battles]

Role of the social media platforms

The online violence against Ressa has been most pronounced on Facebook, which is the only way most Filipinos access the internet. It’s also the primary platform through which Duterte and pro-Duterte online trolls instigate online violence against Ressa and other journalists.

Facebook’s inaction in combating the hate and disinformation on their platform has enabled the life-threatening, antidemocratic crackdown on her to flourish, Ressa has often warned. In this report, Ressa compares the pervasiveness of disinformation on Facebook to the coronavirus: “It’s a perfect comparison to the COVID-19 virus, because the virus of lies is very contagious. And once you're infected, you become impervious to facts.”

Holding the Big Tech platforms accountable is crucial, said Ressa. Otherwise, the rampant disinformation and its consequences for democracy in the Philippines will be replicated in the rest of the world.

“The only way it will stop is when the platforms are held to account...because they allow it,” Ressa is quoted as saying in the report. “It's kind of like if you slip on the icy sidewalk of a house in the U.S., you can sue the owner of the house. Well, this is the same thing. They have enabled these attacks. They've certainly changed my life in many ways.”

Recommendations

The report offers 10 recommendations to address online violence against women journalists today drawing lessons from Maria Ressa’s experience. Among them, the researchers urge that political actors be held accountable for inciting violence against women journalists, and that legal and regulatory frameworks upholding freedom of expression and equality be reviewed and adapted for the Digital Age. They endorse the establishment of social media councils that offer recourse for victims of online abuse, and advise social media companies to develop specialist teams to respond swiftly and effectively to online attacks against journalists.

News organizations should provide gender-sensitive training and guidelines for staff, as well as integrated digital and physical security, and psychological support for women journalists targeted by abuse. Newsrooms should also produce reporting that holds social media platforms accountable for their actions — or inaction — and their policies, regardless of any ties they might have with the companies.

A full list of recommendations, and further resources, can be found in the report here.

If you've found this content distressing or difficult to discuss, you're not alone. There are resources available to help. Start by exploring the resources from the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, and please seek psychological support if needed.

David Maas is the director of IJNet.

Main image supplied by Franz Lopez of Rappler.