This piece is part of a series of articles by Chicas Poderosas (Powerful Girls), a global community that promotes female leadership and generates knowledge. Read other articles by Chicas Poderosas here, and join the community on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

These days it is common for journalists to be overwhelmed searching for relevant and reliable sources online. Although it sometimes feels harder than finding a needle in a haystack, there are many free digital tools that can make the process easier.

These six tips can help journalists be more effective in their investigations.

(1) Use advanced search to find quality sources

Investigative journalism requires on-the-record sources to back up our claims and give context to our findings. For this reason, our references should be diverse, trustworthy and balanced in every way. However, when using a search engine to look for the right sources, unverified publications often get in the way.

One way to make this easier is using advanced search operators. For example, by adding “filetype” to our query we can search for specific formats like PDFs or Excel spreadsheets. For example, if we’re looking for statistics on poverty, we can add “filetype” to our query by typing, “poverty statistics filetype:xls.” We will quickly find the specific files we need without spending time going through irrelevant results.

Another key search operator is “site,” which lets us look within a particular domain or website. For example, if we want to find the last COVID situation report published by the World Health Organization, we can try searching “covid site:who.int.”

In the event we don’t know exactly where the information is, we can search by just a domain suffix. For example, to look for official sources on poverty published by a governmental entity in Mexico, we can use “poverty site:gob.mx” to make our search more effective.

[Read more: 5 tips for journalists working with whistleblowers]

(2) Check and double check

When approaching a research topic, we’ll find data, claims, images and documents that may not necessarily be accurate or true. For this reason, it is very important to verify the information both at the beginning and the end of the investigation.

If we see a phrase that looks suspicious and want to check whether it has been published in the past, we can search it between quotation marks to see other places where those exact words appear on the web.

For example, if we want to verify if Sherlock Holmes ever said, “elementary, my dear Watson,” we can use quotation marks to search the phrase inside Google Books. The search engine will scan Arthur Connan Doyle’s complete work, and we will realize that it was never exactly said in one of his publications.

We can use a similar strategy if we see a sentence or paragraph that we’d like to have more context about or that looks like plagiarism. We can search the phrase between quotation marks to see if it was published on another website in the past.

Also, if we want to check whether a politician or public figure has used a phrase on social media or want to track down a particular tweet, we can combine that phrase with the operator “site” to make our query more precise. This might look like: “‘Earth is square” site:twitter.com/*username*.”

If a false claim spreads, such as “WHO recommends not wearing masks in public,” we can search different combinations of that phrase to see where it appeared first.

To assess the origin and validity of pictures, we can use reverse image search. You can search a photo to find similar results and see a list of websites where it has been published before. This method is always the first step to bring context to any visual piece of information.

To reverse image search, either right click over an image and select “search Google for image” on Google Chrome, or directly upload the image to Google or other search engines.

[Read more: 9 tools for verifying images]

(3) Search for context to find the angle of the story

When starting a research project, we should ask ourselves what exactly we expect to find out. Broad topics are often tempting, but they’re impossible to cover. It’s critical to narrow down the scope of the story.

If we try to find out how one country’s health system works, for example, we’re likely not going to find something worthy of being published. However, if we are guided by an editorial line — in the case of Chicas Poderosas, underrepresented stories with a gender perspective — we can find a more specific angle to our story. One example might be HIV positive people’s access to healthcare between the ages of 20-29 in Mexico.

(4) Set up alerts to discover updates

It’s important to never miss updates on the subject we are researching. A key tool for that is Google Alerts, which scans every publication on the web related to a given keyword, and sends an email daily, weekly or instantly with a summary and links to new results. Alerts can be set to monitor specific people or topics so we can follow new publications that reference a given source until the end of our investigation. For example, if we want to keep track of every new publication related to gender-based violence, we can set alerts for “femicide,” “intimate partner violence,” “gender microaggressions” or other relevant keywords.

When setting an alert, be precise. To make our alerts more accurate, we can apply the search operators mentioned above. For example, if we want alerts to return information published by social organizations in PDF format, we would add, “filetype PDF site:org."

(5) Turn images into text

In your search, you might find useful tables with data, but not necessarily in the format you need. This is common, as many reports are published as PDFs or illustrative graphics. A manual transcription of the data would take too long, but there’s another way.

First, upload the picture or PDF to Google Drive. Then right click over the file and select “Open in Google Docs.” Google will create a document with the image, but also with a text transcription below.

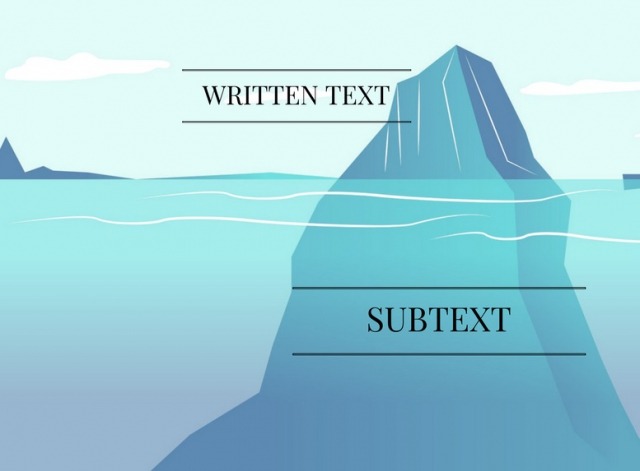

(6) Consider "Iceberg Theory"

After a long investigation, we have to leave out part of our work in order to make the final product attractive, simple and clear to the average reader. According to Ernest Hemingway’s iceberg theory, if an investigation is well done, only 25% of the findings are visible in our final story — just as only the tip of an iceberg is visible, and the rest is hidden underwater.

What we place underwater and what we decide to let our readers see will depend on our journalistic criteria. This includes not only teasing out which elements add new information to public discourse, but also choosing the most important angles for our society.

Nicole Martin is an investigative journalist based in Argentina and Ambassador of Chicas Poderosas. She is also a member of the 4th generation of Distintas Latitudes (MX) LATAM Network and Co-Founder of Revista Colibrí.

Carla Nudel is an Argentinean journalist and trainer specializing in digital tools and media innovation. She leads the Chicas Poderosas community in her country.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Markus Winkler.