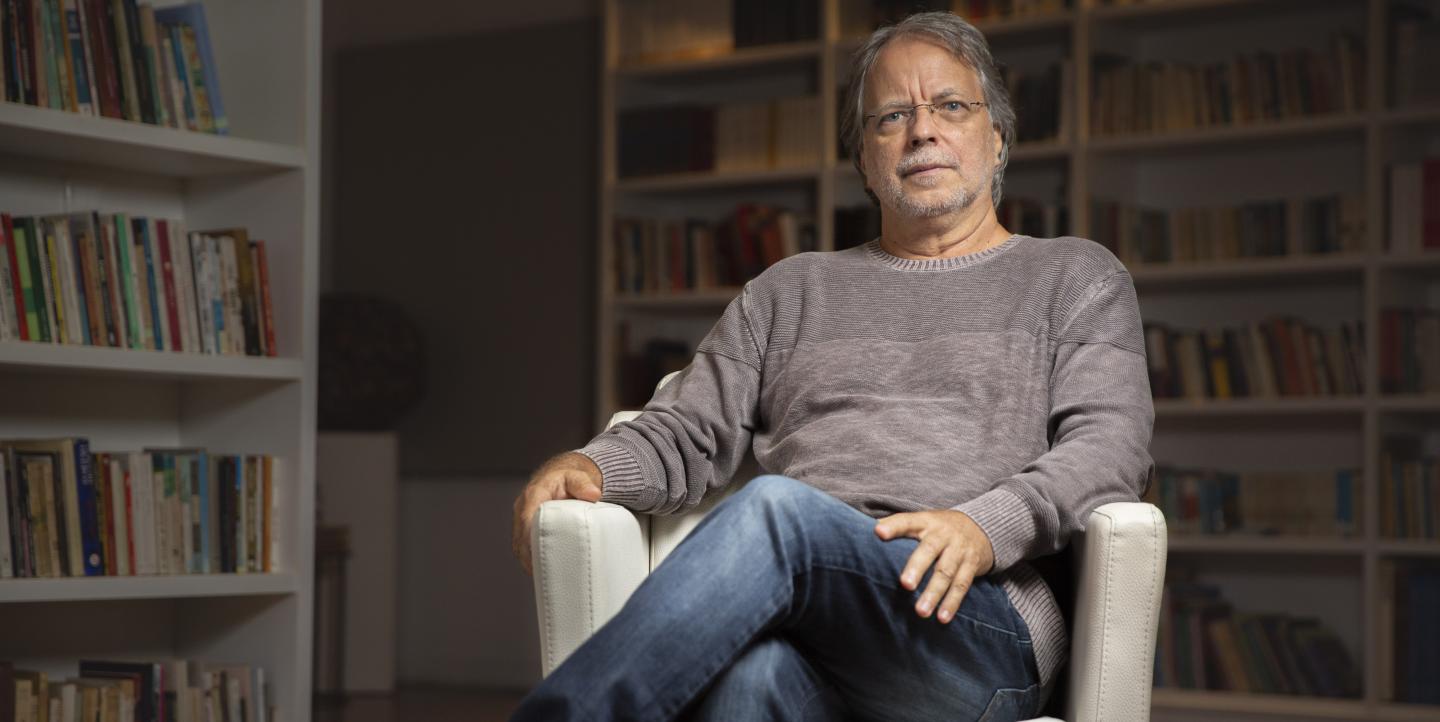

On July 5, 1955, in the coastal city of Beira, Mozambique, Mia Couto was born. This is the pseudonym of António Emílio Leite Couto, one of the most renowned African writers on the continent and abroad. In 2013, he was awarded the Camões Prize, the most important literary honor in Portuguese-speaking countries, and he is the only African writer to become an elected member of the Brazilian Literature Academy. Recently, he was granted an honorary doctorate by the Júlio de Mesquita State University in São Paulo.

A journalist and writer, Couto has published more than 15 books, most of them novels in which he explores African cultural identity. I reached out to Couto to learn more about his views on journalism and literature.

Here are some takeaways from our conversation:

You started working as a journalist in 1974, when Mozambique was about to become an independent country. What was being a journalist during that time like?

Everything was different. The country, the media, the journalists, the national and international context. I became a journalist because I wanted to, but also as a duty of activism. I was taught how to work for a newspaper. It wasn't something new for me. My father was a journalist himself, and my older brother was already working for [the newspaper] Notícias when I started working for [the newspaper] Tribuna in 1974.

Tribuna was an afternoon paper that politically opposed colonial rule. It was helmed by the great poet Rui Knopfli. José Craveirinha and Luís Bernardo Honwana worked there. When I joined the team, some other young Mozambicans joined too, like Luís Patraquim, Julius Kazembe, Ricardo Santos, Benjamim Faduco. We felt we were on a mission and the political commitment was unanimous.

The newsroom was definitely the place where we wanted to be all day long, regardless of how much we worked or the paycheck. There was a national purpose to fight for. There was a socialist revolution going on that excited us. That was a different time. I could not repeat this kind of prowess again.

What made you quit journalism to become a writer?

I no longer believed in the truth behind the cause that made me quit college. But I have no regrets. On the contrary, I owe much to those revolutionary times. I did not make any personal profits, but I grew as a person, and I know that I am who I am now due to how I connected with other people.

Journalism was like a school to me. I learned how to read this large country and its great diversity and complexity. Journalism was like a school for my literary labor — I knew I was writing for someone else, and the awareness of the reader was nearly instant. On a deeper level, I was interviewing people and reporting so I could reveal people's existence and their stories. I didn't know by then, but I was already into literature.

It's been more than 30 years now since you stopped being a journalist. Do you feel that journalism has changed since then?

There have been profound changes in journalism globally. When it comes to journalism in Mozambique, it was nice to see the rise of independent media outlets. Some would question the term "independent" because supposedly there is someone behind it. Even if this holds true, it's good to have different forces that are able to express different points of view.

I think that what I consider to be the heart of journalism has really scaled back: the news reporting and investigative journalism. Most of the newscasts in radio, TV and newspapers are devoted to talk shows and opinion makers. Readers and viewers should have the right to, first and foremost, have access to information delivered by the work of good professionals. They don't need other people chewing over opinions on their behalf about facts that, most of the time, are not properly reported as they should be.

In recent years journalism all over the world has been challenged by influencers who consider themselves news publishers, and by misinformation. What are your thoughts on this?

I think the debate, and the ideas in general, have become poorer. Thoughts have become a cheap commodity. They are no longer critical nor productive. The general feeling of intolerance and political polarization have replaced public debate with insults, and the search for the truth with slander and fear.

There is no easy way out of this because fake news brings a lot of returns ideologically, financially and politically speaking. Populist politicians and far right dictators profit from this permanent war and crisis environment. No one cares about the real causes of a social phenomenon. They only want to know whose fault it is.

Press freedom in Mozambique is just as new as democracy in the country. Is this freedom effective?

It's formally effective. However, it was under this state of freedom that journalists like Carlos Cardoso were killed. Some others were threatened and abused. Those threats don't always come from political forces, but from those in power who know they won’t be punished. There won't be freedom of information while there is freedom and impunity for those who attack journalists. Many times, the threats are not made against people. But the industry dictates some rules that are far from democratic.

For instance, in most newspapers, magazines, and on TV and radio shows, the arts and culture coverage has been cut back, as has coverage of civil rights.

Journalist Carlos Cardoso was killed in 2000. He is considered a symbol of investigative journalism in Mozambique. What do you think about investigative journalism today and the violence directed at journalists?

I believe this kind of journalism hasn't survived in most countries. I think fear has won. After years of threats winning over any attempt at investigative reporting, it's hard for journalism to prevail. It's been a long time since I last read a good investigative article published in Mozambique. We are left with big outlets like the BBC and Al Jazeera. However, even in these cases, you can see there is not much room for journalists to move.

What advice would you share with young journalists?

Respect the truth and defend the truth no matter what. Don't let yourselves be bought off. Journalism must regain its role in building a better world.

Photo by Fundação Fernando Leite Couto.

This article was originally published on our Portuguese site. It was translated by Priscila Brito.