With more than 2 billion people actively using social media each month, its stake in journalism is a no-brainer.

Though Facebook makes up more than half of these users, every instant messaging, micro-video or networking app that pops up represents a new platform for telling a story, and newsrooms are taking advantage of that.

Here are some of the most interesting ways social media was used (and misused) to cover a few of the biggest news events of 2014.

The World Cup

Journalists covering the biggest social media event ever were active on Twitter, using it to report on both the sports and stats as well as the surrounding social commentary and goings-on in Brazil.

As part of their coverage, AP photojournalists throughout Brazil used Instagram to highlight “offbeat, behind the scenes views of soccer’s premier event.”

Fusion, a news and entertainment cable network focused on millennials, used live-blogging as well as the “honeycomb,” a social aggregator built on Fusion’s soccer site that allowed them to surface social media content based on location and influence. For this coverage, two to three Fusion editors at a time mined and tracked all 12 stadiums where the tournament took place based on certain key elements like hashtags and the influence of people in the stadium, IJNet reported back in October.

Some journalists also used social media data to inspire and inform stories. For instance, during the United States-Germany game, journalist Reuben Fischer-Baum wrote about how “Nazi” was used over 30,000 times on Twitter, especially in the minutes surrounding a goal from Germany. This proved that “stereotypes are common crutches when it comes to trash talk,” CJR wrote, adding: “It will be interesting to see how social media data develops as a real-time source to explain people’s behavior with regard to sports and beyond.”

Ebola

In July, journalists around the world began scrambling to cover the deadliest Ebola outbreak in history. This has been a challenge not just for the deluge of misinformation that has circulated on social media, but also because of a slow and minimal social media presence in locations where the outbreak is strongest.

In addition to public health sites like WHO, BBC Africa was a strong Twitter influencer on Ebola, according to data from health care social media analyzer Symplur. The BBC also launched an Ebola public health information service on WhatsApp, aimed at users of the service in West Africa. The service provided “audio, text message alerts and images to help people get the latest public health information to combat the spread of Ebola in the region,” according to the BBC.

From Sierra Leone, The Guardian’s Channel 4 News Chief Correspondent Alex Thomson made news after his Vines showed snapshots of the situation, which packed an emotional punch despite their short length.

“Just as the tweet is the boiled-down version of the blog post, which is the boiled-down version of the essay, a Vine is the boiled-down version of a TV package, which is a boiled-down version of a documentary,” Marc Blank-Settle, a mobile journalism and social media trainer at the BBC College of Journalism, told The Guardian. “The tool itself is brilliantly easy to use. It’s really leveraging the power of Twitter to share news and information very quickly.”

Ferguson Protests

Fusion’s Director of Media Innovation Tim Pool is the epitome of social storyteller. Pool, a college dropout, first became known in journalism for using drones and wearables to live-stream breaking news events, from the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011 to demonstrations in the Middle East. His unique style exists at the intersection of social and mainstream media.

After protests erupted following a grand jury’s decision not to indict the police officer who shot Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in the U.S., Pool was on the scene for Fusion, as well as publishing content on every major social channel, including Twitter, Instagram, LiveStream, Vine and YouTube. He used these channels to bring stories on the ground to his tens of thousands of followers.

While he was covering the protests, Pool even managed to conduct a Reddit AMA (“Ask me Anything”) which garnered almost 600 comments.

Pool is open about his dislike of the way the mainstream media, or “MSM,” often covers stories, saying “It's the small stories within the larger story that MSM misses … They offer this blanket coverage and you miss the most important moments.”

“I think the future is for the individual,” Pool wrote. “Newsrooms will have to adapt to having their channels be a collective and not a single channel.”

Conflict in Gaza

Opinions and information flooded social media platforms as Israel's offensive in Gaza began in July. But social media was also full of an unprecedented amount of misinformation and bias, creating an “information war,” and a challenging environment for journalists covering the story.

Analysis by Abdirahim Saeed of BBC Arabic found that some of the pictures circulated on the popular #gazaunderattack hashtag were recycled images from as long ago as 2007. Some were not even from Gaza. So media organizations had to use reverse image search tools — that show if a photo has previously been published online — to determine the source of pictures, according to Chris Hamilton, social media editor at the BBC. "Social media is kind of a misinformation accelerant, and at the same time, it is potentially the best rumor-smashing tool," Craig Silverman, one of the authors of the Verification Handbook, told the Global Editors Network in an interview.

In a conflict in which it is especially difficult for journalists to be unbiased, a few journalists stood out (and were congratulated) for their fair coverage via social media. Ayman Mohyeldin, a foreign correspondent for NBC News, was pulled out of Gaza and then sent back a few days later after a social media backlash. His coverage of the conflict earned him the respect of fellow journalists. And the New York Times' Jerusalem correspondent Jodi Rudoren used her Facebook page to spur discussion and debate throughout the conflict.

Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17

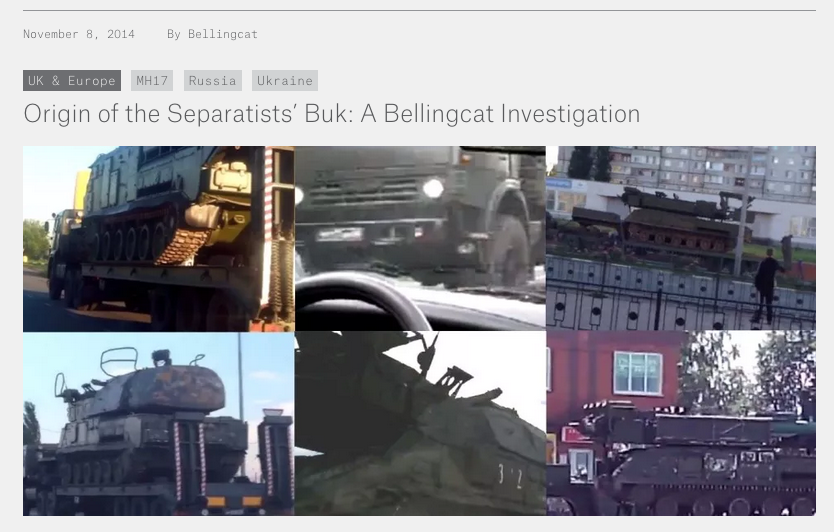

In the immediate aftermath of the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 on July 17 by a Buk missile system, journalists and social media experts took to the Internet to “sleuth” the event themselves in the absence of official information.

Using images and videos, Storyful’s Open Newsroom project confirmed members of the Donetsk People’s Republic separatist militia “at the very least” appeared to have access to an anti-aircraft missile system capable of an attack like the one carried out on the plane.

And Eliot Higgins, the British founder of online journalism site Bellingcat, with the help of some of his Twitter followers and open source tools, used a YouTube video to pinpoint the location of a Buk launcher while it was being transported through a pro-Russian rebel-held town in Ukraine near the Russian border. In November, less than four months after the crash, Bellingcat published a 35-page report outlining “solid information” that the Buk missile system that downed Malaysian Airlines flight 17 came from Russia and was sent back there after the disaster. As Mashable wrote, Bellingcat was able to unearth “MH17 intel quicker than U.S. spies.”

Image courtesy of Flickr user Ian Clark under a CC License.