With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine entering its third month, the work of journalists continues to be instrumental in informing the world on alleged war crimes and civilian suffering. While covering the events in Ukraine – as well as other conflicts where journalists are at risk, from Afghanistan to Yemen – reporters need to know both hard safety skills and the complex ethical considerations unique to reporting on conflicts.

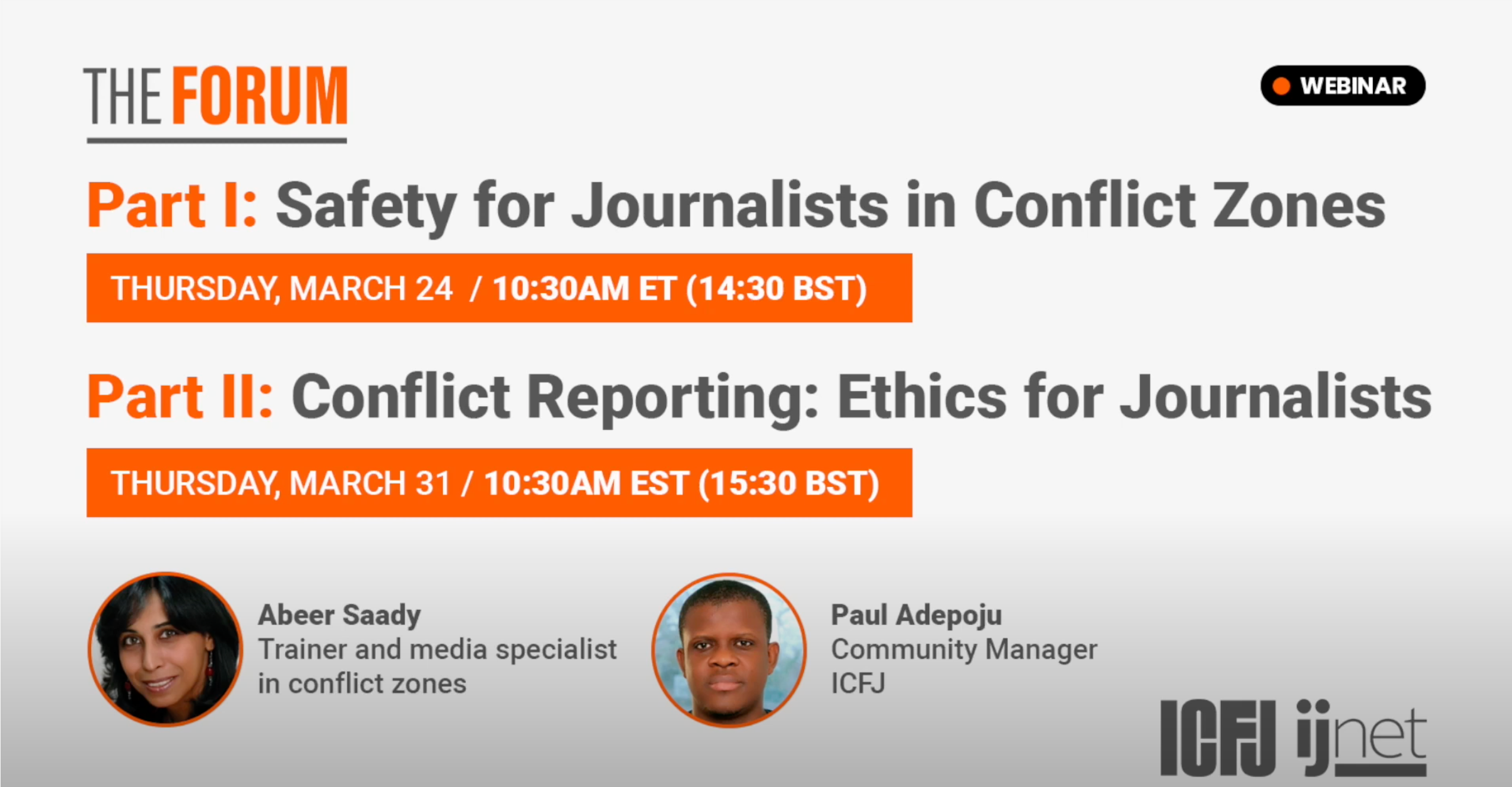

Abeer Saady, a war correspondent and conflict media specialist, who has over 27 years of experience reporting in conflict zones, recently shared ethical rules for covering conflicts during the second part of ICFJ Global Crisis Reporting Forum’s two-part webinar series on reporting in conflict zones.

Here are some highlights:

Covering armed groups

Whether embedded within a military unit or reporting in an area controlled by armed groups, knowing the relationship between these actors and journalists is the first thing any reporter should consider. “We have to know that we are there for a different reason than the armed forces are,” said Saady. “Working in the same place doesn’t put us in the same situation [as a soldier].”

While covering areas controlled by armed groups, Saady stressed that it is important for journalists to fully acknowledge their own identity in the context of the conflict. Anything from your nationality or ethnicity, to what language or dialect you speak, to the publication or media house you’re reporting for, can have an effect on your relationship with military forces. These factors can influence what side of the conflict these armed forces believe you are on, and they can affect your safety. Your personal background can also influence how you view the conflict and the military’s role in it.

Ultimately, it’s up to journalists to do proper research on the political and societal situations going on in the areas they report in. Reporters should also become familiar with the armed group’s ideological background and the foreign support it receives, to both keep themselves safe and report fairly and accurately on the conflict.

Interviewing survivors

Interviewing survivors of traumatic experiences is a delicate task for journalists. Reporters must ensure that the interview isn’t making their source experience any additional trauma. “Your responsibility is to, at least, don’t harm people,” said Saady.

Having certain rules set before interviewing survivors is an important first step to minimizing harm. Approach survivors clearly, calmly, and tell them in advance that the interview will be published or broadcasted. “You really have to say who you are, what you are doing, because they are not obliged to answer you,” said Saady.

In the course of an interview, Saady warned against asking questions such as “how do you feel?” that might be difficult or traumatizing for the interviewee to answer. Instead, begin by asking simple questions about facts, dates and times, or about what they saw or heard. As your source becomes more comfortable, let them begin to open up on their own.

Journalists should also avoid promising their interview subjects anything. Instead, say that you’re going to write the story, and that you’re going to try to have it published – as even publication of a story is never certain.

To save or not?

In the midst of a conflict, there are situations where a reporter might be presented with the “save or not” dilemma, in which a civilian or fellow colleague is at risk nearby. Saady presented three questions for journalists to consider if this occurs:

- Are you yourself in danger?

- Are there others able to help?

- Can you cover what is happening and still help?

Ethically, Saady said that it is important for a journalist to ensure their own safety first. If others are available to help – soldiers or medical personnel, for instance – allow them to do so and continue reporting. “You have to save yourself and then others,” she said.

Only if there is no present danger to yourself or others, and doing so doesn’t impact your coverage, should a journalist step in. This isn’t just a personal safety concern – risking your life means possibly losing important coverage of ongoing events or atrocities. “The biggest help as a journalist is to be there and report – your presence is very, very important,” said Saady.

The publishing dilemma

There are times when publishing an interview or photos, or broadcasting footage might be ethically problematic. In these cases, it’s important to consider if publishing the story will be more detrimental than not publishing it. Content that glorifies violence – such as photos of clearly identifiable bodies, especially of enemy combatants – is one scenario in which a story or photo shouldn’t be published, said Saady.

In instances when the decision to publish is more uncertain, Saady suggested taking into account three considerations. The first is if the coverage is essential to the public. For example, during the assassination of President Anwar Sadat of Egypt in 1981, a photo showing the gunmen at the time of the assassination provided important context and a snapshot of the moment to the public – context that could be achieved without showing Sadat’s body after his death.

Second, consider the harm survivors may experience if a story is published, especially if their identity is revealed. Journalists should have a clear justification for their publishing decision in the context of the conflict, and after considering fully the risk it might pose to igniting further violence.

Finally, for reporters covering conflicts around the world, understanding your responsibility and role as a journalist is paramount. “My role is not to convince people, but to present as much as possible to let people know [what is happening],” said Saady.

“At the same time there is the politics of justice. You are there not to make people cry about this conflict, you need people to know what to do, [how] to act, [and] what the situation is. You need to prove that there are people on the ground who are civilians who need to be protected.”

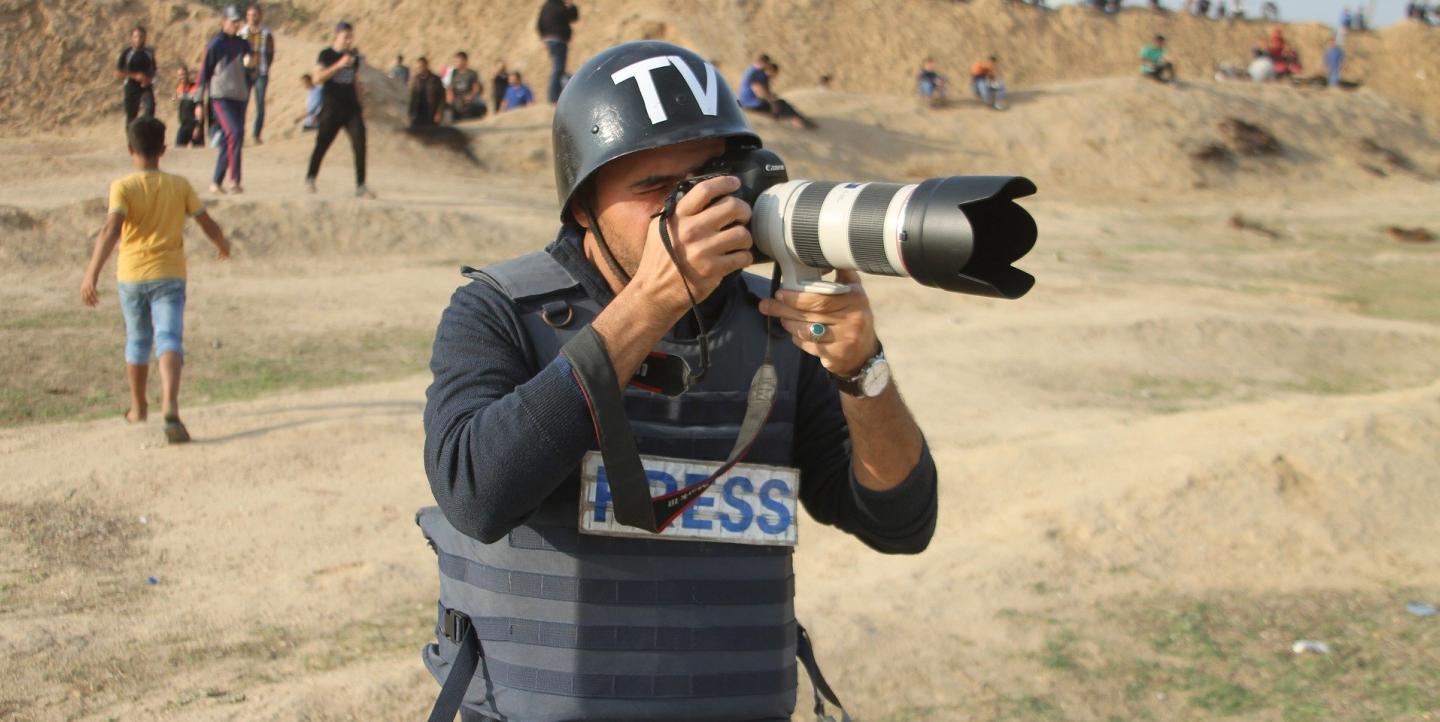

Photo by Hosney Salah on Pixabay.