“I really didn't set out to do an environmental story,” explained photojournalist Larry C. Price at “Global Environmental Storytelling,” part of the Environmental Film Festival in Washington, D.C.

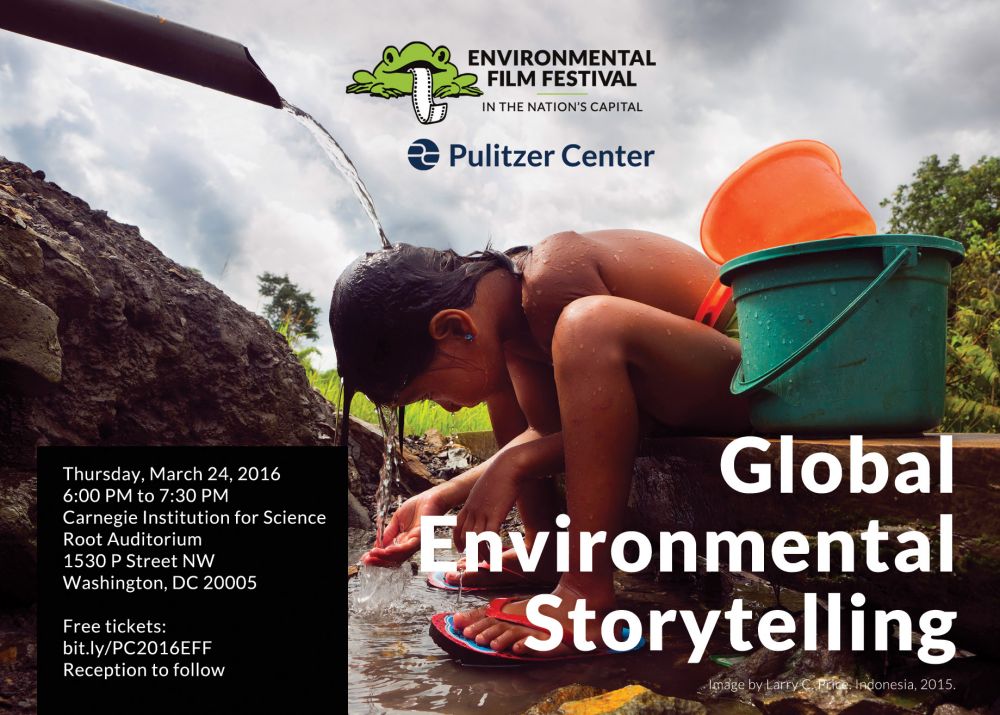

Yet Price, who had initially set out to report on gold mining, quickly turned his attention to the human costs of using mercury in gold mining — particularly in the developing world. Alongside producer P.J. Tobia, he created a short film series showing the damaging effects of mercury in Indonesia’s small-scale gold mining industry for PBS NewsHour.

“I became more and more curious about the use of mercury [in gold mining],” he said. “I made four or five trips to Asia working on these pieces, and I was just taken aback by the number of children who were surrounded by this heavy metal, this pervasive and toxic element, anywhere you have gold."

“Global Environmental Storytelling,” which was co-organized with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, showcased three short documentaries produced across the globe. A common thread wove its way through each film: the telling of critical environmental stories through a powerfully human angle.

In "Pumped Dry: The Global Crisis of Vanishing Groundwater,” journalists Ian James and Steve Elfers covered the growing crisis behind falling groundwater levels around the world. James, who had previously been covering the California drought at The Desert Sun, linked a local issue to a global one by chronicling how groundwater shortages are playing out across the globe, from Peru to India.

“The idea of the project was to go to several of these places where there's intensive agriculture and where aquifers are in decline and look at what the causes are, and what the impacts on people's lives are,” he said.

For each filmmaker, developing trust with one’s subjects played a vital role in bringing these stories to light.

This was especially so for multimedia journalist Sharron Lovell, who worked on a film chronicling China’s massive south-to-north water transfer project. Lovell explained that many potential interviewees, fearing persecution from the government, refused to appear on camera and share their thoughts on the project.

“All I can do is be transparent about where it's going to go, and then they make the choice of whether they want to talk to me or not," she said. "There were lots of people who wouldn't talk to me along the way, which was a shame. Especially in the last year, it's been increasingly difficult in China. Lawyers wouldn't talk to me; NGOs wouldn't really talk to me.”

In the end, some people felt their need to speak to the press was stronger than the fear of negative repercussions.

“There's a text article coming soon where another guy kind of says, ‘I know I can get into trouble for this, but I want to say my piece,’” she said.

In Price’s case, simply finding communities affected by mercury was as much of a challenge as getting people to trust him, as many are located in remote areas.

“In many ways, it's probably one of the hardest stories I've ever done, but I know all I can do is come in and take the pictures and make the film and try to get the people to trust me,” he said. “What I did learn is that the individuals were just happy that somebody was paying attention to their story.”

To watch the documentary films featured, click here.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via Aaron