Tracking the impact of COVID-19 in Peru's remote Amazonian jungle with spotty cell phone service is a daunting task. But, this is precisely what ICFJ Knight fellow Fabiola Torres and her team at Salud con lupa worked for months to make happen.

Through on-the-ground reporting, they found that the number of fresh graves in just one community was three times higher than the number of deaths the government reported for the entire region.

Little access to diagnostic tests, a spike in dengue fever, and a reliance on natural medicine were among the reasons why many COVID-19 deaths in the Peruvian Amazonia were left out of the official count. The most important reason, however, according to Torres, was “a lack of care.”

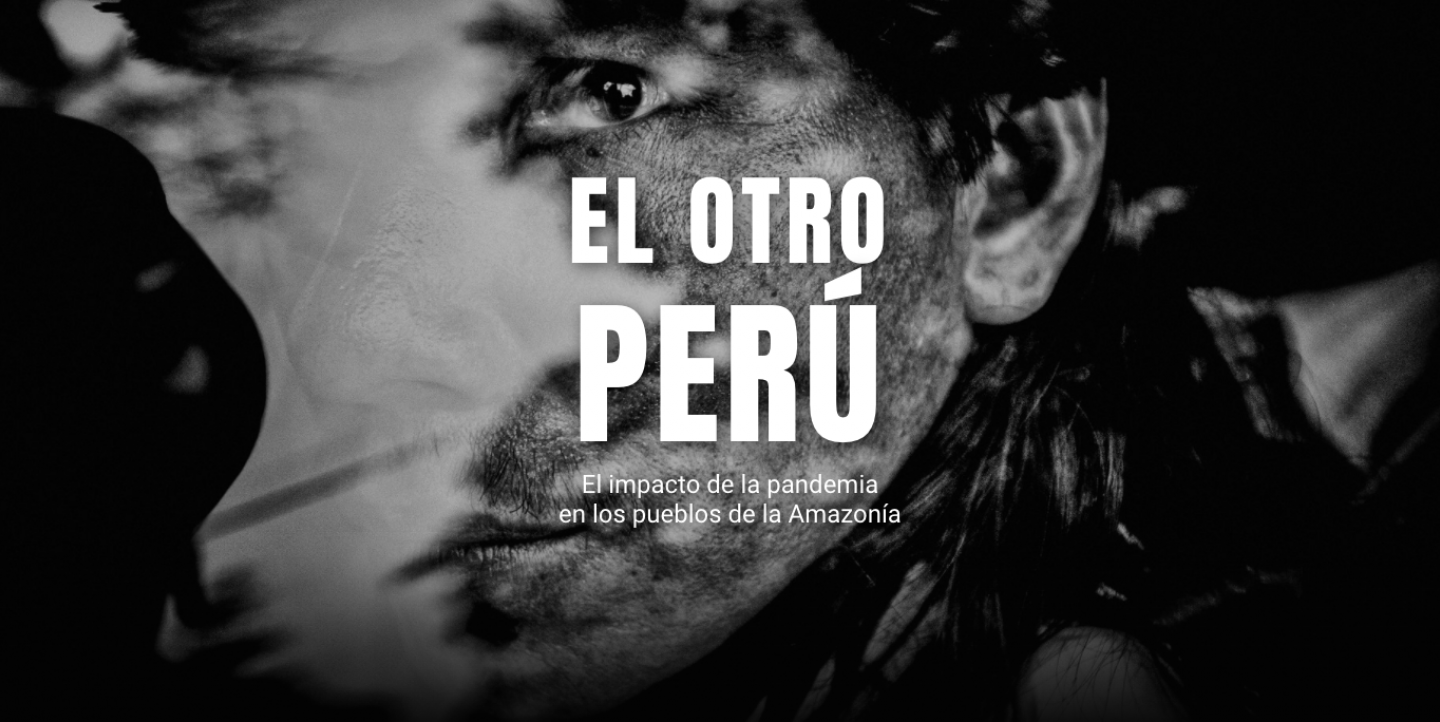

Torres founded Salud con lupa in 2019 to cover health news in Latin America — including in the often ignored “Other Peru” of indigenous communities. In the interview below, read about how she brought this story to light.

[Read more: Reporting on COVID-19 in hard-hit India]

Can you introduce us to El Otro Perú (The Other Peru)?

The project exemplifies a challenge in countries like mine and other Latin American countries that don't have enough data. In this case, we focused on indigenous communities in the Amazon.

Since the pandemic started in Peru, we didn't have data about this population because of a lack of access to health services. Nobody was registering COVID-19 deaths. That's why officials and the Minister of Health didn’t provide an official report about the impact of the disease in this part of the country.

We worked to gather data and to try to understand what happened. To do so, we had to make a lot of requests for information. We built a database on our landing page and featured stories to provide an explanation. It’s important to investigate because indigenous communities are at risk if we don't identify who died.

What were the major challenges that you encountered when collecting this data?

The principal challenge was the requests for information from authorities. We were constantly told that there is no data, or only partial data. Most of our attempts were successful if we contrasted the official numbers with the information that people gathered in the field. That information was collected by interviewing many indigenous leaders as a more reliable source.

[Peru’s] Minister of Health reported 148 indigenous deaths during the pandemic. This is false. We know that more than 400 died, just in one community. It shows you that they are not taking care of the data, and they are not documenting what happened. It was our goal to tell the real story.

It sounds like the government completely overlooked these communities.

Yes, we are trying to expose to Peruvians what happened in this part of our country. If you go to the [investigation’s] landing page, you will see that we feature a cemetery full of unmarked graves. Now, there is an effort for many families to try to identify their loved ones buried there.

This is something that shows you the true impact. It's impossible that official data represents our reality. This is why, as journalists, we decided to invest the time in this project.

[Read more: Tracking COVID-19 equipment and relief funds in Zimbabwe]

Was there anything else that surprised you during your investigation?

Yes, we know that the epidemiologists and the Minister of Health in Peru have information. They built a website, but it features selective information. That's a surprise to me because in March of this year, they created an independent group of scientists to track the numbers related to the pandemic. Peru is one of the countries that had the highest mortality rate from COVID-19 in the region.

But all of this data is generalized. When you want to search by ethnicity or indigenous status, we don't have the answers. We interviewed the scientists who did this work and they said that there was no way to filter this information from the official databases.

It surprised me because the most vulnerable people in my country are indigenous, and they are far from the capital. It shows a lack of care as to what happened in that part of the country because they didn’t collect the information, despite having the resources to do so. The official account is not true.

What advice can you give to journalists who wish to pursue a data project of this extent?

It's very important to work with requests for public information or public data. But if that falls short, try to build the story with other sources. Many people may read the project because they find little substance [when they] search for information.

You know that there is a reality in front of you, but it is not revealed by official numbers. Some reporters will say that if we don't have official data, we don't have the story, but it's not true. There are alternative ways to approach the problem and paint an accurate picture of the situation.

El Otro Perú can be found here. Readers interested in the data gathering process can begin with the story methodology.