María de los Ángeles Ramírez and Joseph Poliszuk were 2022 fellows of the Rainforest Investigation Network (RIN), an initiative of the Pulitzer Center. Read their reporting here.

After we finished our 2022 investigation about airstrips tied to illegal mines, we were sitting on some clues about a network of criminals smuggling gold between Venezuela and Brazil. We wanted to learn about their modus operandi and uncover their corporate networks. We created databases, extensively reviewed piles of judicial files and did traditional on-the-ground reporting in Venezuela, Brazil and the United States. It turned into our next investigation, The Lords of Gold. Our main finding was that illegal gold smuggled from Venezuela to Brazil was being paid for or exchanged with food, at the time of the biggest food crisis in Venezuela.

The investigation was a trending topic on social media and was featured on news programs in Venezuela and northern Brazil. United Nations agencies and other international organizations contacted us to understand the main findings of this investigation and include them in their reports and policies. A curious fact is that a couple of weeks before publication, one of The Lords of Gold escaped from his house arrest.

Data sources

- National Registry of Legal Entities (CNPJ): In this registry, we found details of the Brazilian companies behind the exchange of gold for food.

- International databases with corporate information: Sayari, Aleph, Open Corporates.

- ImportGenius: A database of imports and exports that can be filtered by products, companies, origin and destination.

- Comexstat: The foreign trade statistics of Brazil. It can be searched by state, product, destination and origin, among other options. The Comex Vis visualization tool was very useful. It allowed us to understand the characteristics of the record food exports experienced by the state of Roraima in Brazil, bordering Venezuela.

- Digesto: A paid service to access judicial files. A free alternative to this database of court records is JusBrasil. In both cases, you can search for a person's name and the platform displays the cases associated with that person and the court.

- Commercial Registry in Venezuela (offline access): We used this to track companies and key players behind the illegal mining in Venezuela.

- Satellite imagery: We used Google Earth, Planet and Earthrise Media.

- Florida Division of Corporations: The gold lords had companies registered in Florida and we were able to get their details here.

- UN Comtrade: This is a global foreign trade database that shows the reported overall figures of products imported and exported between countries.

- Social networks: We looked at Instagram, X/Twitter and Facebook to find contacts and details about companies and people.

- Official and unofficial interviews with multiple sources.

- On-the-ground reporting in Brazil, Venezuela and the United States.

Methodology

The informal networks smuggling Venezuelan gold have rarely been reported on in a systematic way. For our previous project we had used artificial intelligence to map illegal mines and clandestine runways in the Amazon, with the support of the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN). For our second investigation, we had to find a new methodology to document the cases outside the country that Venezuela’s justice department does not prosecute, ignores and even covers up.

(1) Access to court files

We combined judicial filings from Venezuela and the Brazilian city of Boa Vista about cases of gold that had been trafficked from mines south of the Orinoco River, deep in the Venezuelan jungle. We found preliminary documents in the online database of JusBrasil, and with the help of colleagues and lawyers, got some of the actual judicial files, one of which had more than 30,000 pages.

We learned that gold smuggled across the border entered the Brazilian market as “scrap gold,” referring to gold that has been damaged or is no longer considered useful, like broken jewelry. From this border area, the gold was transferred to one of the main gold exporting companies in Sao Paulo and from there to the rest of the world.

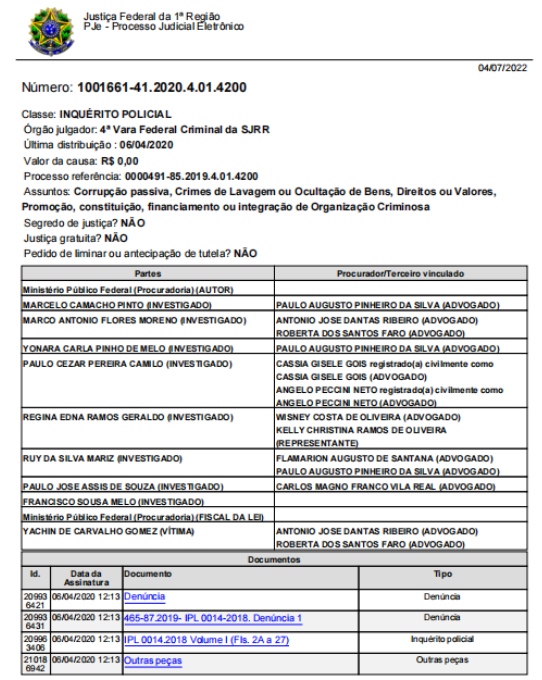

Screenshot of one of the first judicial documents obtained through JusBrasil.

Credit: María de los Ángeles Ramírez, Joseph Poliszuk

(2) Database construction

We built spreadsheets based on the court cases with more than 30 companies and 70 people and cross-referenced this information with Brazil’s CNPJ and Venezuela’s National Electoral Council registry.

Through sales and transportation receipts and bank transactions listed in the court files, we found that companies and partners of the governor of the Brazilian state of Roraima, Antonio Denarium, are related to suppliers, beneficiaries and members of the mafias that exchange food from Brazil for gold from Venezuela. We also discovered links between the mafia groups and crimes committed in the Dominican Republic. Finally, we mapped the business connections of the companies through databases such as Sayari, OpenCorporates, and OCCRP’s Aleph.

Corporate map of Antonio Fernández Soto, one of The Lords of Gold - screenshot from Sayari

Credit: María de los Ángeles Ramírez, Joseph Poliszuk

(3) Fieldwork in Venezuela, Brazil and the United States

Once we had analyzed all information from the court cases, we went to Boa Vista and Pacaraima, in Brazil's state of Roraima and to Santa Elena de Uairén in Bolívar, Venezuela. Some of the sources and the actors involved in the trade were reluctant to talk to foreign journalists,as we were asking them about an issue that is not talked about publicly and for which there are judicial cases under way.

Still, we were able to go beyond the findings by Brazilian justice and show that some of the accused were still operating businesses in that border zone. One of the traffickers, Marco Flores, not only continues to manage a hotel raided by police, but he also obtained a concession to operate the only gas station that the Venezuelan government has on the border. We confirmed this by visiting the gas station and conducting interviews. We also cross-checked hotel payment receipts with the CNPJ.

We traveled to the community of Chirikayén in Venezuela and analyzed satellite images to evaluate the environmental impact of mining linked to one of the Lords of Gold. We also reviewed UN Comtrade import and export data and saw that, at a time of sanctions on Venezuelan gold, the United States was still importing it.

One of the mines in La Gran Sabana, Venezuela, that has caused environmental damage. It is within hours of walking distance from the Indigenous community of Chirikayén and other Indigenous communities.

Credit: Airbus DS / Earth Genome

Photo by Dominik Vanyi on Unsplash.

Joseph Poliszuk was a 2018 ICFJ Knight International Journalism award winner.

This story was originally published by the Pultizer Center and republish on IJNet with permission.