It’s a journalist’s duty to clearly and responsibly communicate reliable information to the general public. During a global health crisis, like the one we face now with the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, this role becomes ever more critical.

“There is so much ‘fog’ in stories like this, it is your responsibility to try to cut through that to get a clear picture of what is going on,” said Shenzhen-based freelance journalist Michael Standaert, who writes for Bloomberg, as well as The Guardian, Al Jazeera and more. Standaert has been reporting on the virus in China since its outbreak in December 2019.

Especially during crises, journalists need to draw a difficult balance between informing the public and stirring fear. “You want to avoid lulling people into complacency,” said Dr. Stephen Morse, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University. But, you also don’t want to hype it up so much that you create unfounded fear or panic, he added.

In China, this task is even made even more challenging in the face of government censorship. Standaert has found it increasingly difficult to get sources to go on the record, as Chinese citizens fear government warnings or reprimands. “It is insane and worrying that an average citizen thinks they cannot speak their mind without approval of local government officials,” he said.

However difficult the conditions, reporters like Standaert continue to produce stories on the virus. From those on health beats, to those covering the economy, transportation and more, journalists around the world are reporting on this story from many different angles.

To help journalists around the world contend with these stories, we’ve compiled a list of tips below for reporting on COVID-19.

(1) Understand the mood on the ground — then translate it into your work

As with any worldwide crisis, there’s a lot of information circling around, and not all of it is good. The proliferation of information on the internet can mislead audiences, like the image of a man lying dead in the street in Wuhan, surrounded by medical workers. It was dubbed “the image that captures the Wuhan coronavirus crisis” by The Guardian — but there was no proof that the man actually died of the virus.

Visual reporting on the crisis is valuable, but it needs to be carried out responsibly. Reporters should make sure their images accurately portray what’s going on. Sensationalist photos, like the man in the street, give an inaccurate picture and spread fear. “Photographs coming out of Wuhan continue to be important for creating a timeline and archive. Given general distrust of information in China, people really do need to see what’s happening to believe it,” said Betsy Joles, a Beijing-based freelance reporter and photojournalist who has contributed to Al Jazeera, Columbia Journalism Review, National Public Radio and more.

Before you even start photographing — or writing — take in your surroundings, speak to people and understand the mood on the ground. Then, translate that into your reporting, and avoid any content that might contradict what people are actually experiencing.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with relaying fear and uncertainty in a story, if that’s what the mood is on the ground” said Standaert. “But you need to be careful if you’re outside and only hearing from a handful of people.”

[Read more: Tips to remedy health misinformation]

(2) Focus on reporting, not analysis

Opinion and analysis have their role, but it’s too early to really understand large-scale ramifications, said Joles. “I’ve tried to avoid pontificating at this stage because there’s still a lot of reporting to do.”

Don’t follow The Wall Street Journal’s lead, for example, and publish an op-ed that labels China the “real sick man of Asia” — which was widely criticized as racist — and speculates on the country’s economic fall due to the virus. It’s too early to know the long-term financial effects.

Standaert warned against pieces that try to project any political ramifications — either inside or outside China. “We’re only in the 3rd inning of the ballgame,” he said, “and we don’t really know how things will play out.”

It should be further noted that China expelled three Wall Street Journal reporters in response to this article — a worrying step in terms of press freedom, notwithstanding the article’s problematic takes.

(3) Watch your headlines

This piece of advice is directed to all the editors out there: don’t mislead readers with your headlines. With a high volume of information, and the fast pace of social media, many people get their news from headlines alone. Although you want it to be catchy, don’t sacrifice facts for clicks — ever, but especially in the midst of a crisis.

“I actively try to suggest headlines for my stories that are reflective of the situation and not sensational,” said Joles.

(4) Remember: not all figures are accurate

Journalists rely on numbers, and data is a critical part of reporting. However, Dr. Morse warns that data isn’t always reliable.

“When you see figures from an epidemic, or a disease, they’re going to be inaccurate,” he said. “And they’re more inaccurate in the beginning.”

Don’t neglect the data you have available, but make sure your audience understands the limitations and uncertainty behind the numbers.

The infection has an estimated incubation period up to 14 days, which means that it’s possible for someone to contract the virus and not show any signs for two weeks. This leads to a lag in the numbers, said Dr. Morse.

[Read more: Guidelines for determining when a medical study is newsworthy — and true]

(5) Talk to as many different people as possible

The virus affects people across countries, cities and social strata. The experience of those affected in China will not be the same as those in Singapore, which won’t be the same as others in Italy. Even within a country, or city, there exists a great deal of difference.

“People under lockdown are not all sick and dying. Some of them are just bored,” said Joles.

Reporters have a responsibility to do their best to capture the different realities people are living within. “It requires journalists to cast a wide net in their reporting, even if that wide net is just within one city, to seek sources across social strata,” she added.

Standaert stresses the importance of speaking to as many people as possible, especially in countries where censorship is more pronounced. He is finding it more and more difficult in China to track down sources who will provide him an accurate picture of a situation.

“For example, we know a lot of factories are having a hard time getting started. But, a lot of these companies are trying to brush that over,” he said. “You need to talk to the companies, you need to talk to their workers and you have to look from a lot of different angles to see what’s going on.”

(6) Avoid racist tropes

Global epidemics have a history of spreading racism and xenophobia, and COVID-19 — now a pandemic — is no different. Just this week, a Singaporean man of Chinese descent was reportedly assaulted in London, his assailants telling him they didn’t want “his coronavirus.”

Chinatowns in cities across the U.S., including San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York have lost business, too.

The media must be careful not to encourage stereotypes or inadvertently promote racist interpretations. The Asian American Journalists Association published a list of recommendations for journalists. Among their suggestions: add context to photos of people with face masks, avoid images of Chinatown unless they are directly related to the story and don’t use any geographic references in the name of the virus.

(7) Consider the way you interview experts

You might be a phenomenal writer, but if you don’t find the right sources your work will suffer. Take care to research the experts you need, and their views.

“The problem is not just finding a good expert,” said Dr. Morse, “It’s finding people who are going to be sufficiently able to distance themselves from their own biases — or declare their own biases — because we all have a bias.”

Once you identify an expert, interrogate their biases and don’t take their work at face value. Not only does this help you understand their worldview, it also strengthens your story.

Many journalists also rely on modelers to understand how a disease will spread. But, models are based on assumptions, said Dr. Seema Yasmin, a reporter and JSK Fellow, during a recent webinar from the Center for Health Journalism (CHJ) at the University of Southern California Annenberg. Always ask what assumptions they’re relying on.

(8) Don’t neglect stories that aren’t exciting

A worldwide story like COVID-19 lends itself to hard-hitting reporting, in-depth investigations and more. However, not every story you’re going to write will be worthy of a Pulitzer Prize, said Emily Baumgaertner, a medical reporter for the Los Angeles Times, during the CHJ webinar. You might need to write a full-page story on hand washing, for example — and that’s okay.

Focus your efforts on answering your audience’s questions. Use Google Trends to better understand what type of information people are looking for, and then produce quality content they can turn to in order to find answers.

(9) Set your limits

Editors will likely approach you more frequently for stories. It’s important to say no sometimes — for your sake, and for the sake of your work. Taking 24 hours to step away from your computer and regroup will help you return mentally rested, and able to pursue new story angles, Standaert advised. “A good fire needs space between the logs,” he said.

Slowing down to evaluate which stories you want to tell will ensure that you don’t get caught up in the rush. Instead, you can focus on telling a few stories well, said Joles. And, while social media can be a useful tool for connecting with people in other parts of the country — especially if you are being advised to avoid travel or large gatherings — it can sometimes cause more harm than good.

“Limit your time on Twitter,” she added. “It’s an anxiety factor.”

(10) When things wind down, stick with the story

Eventually things will wind down, but that doesn’t mean your job is over. “There’s a lot happening during the aftermath of an epidemic that needs to be covered,” said Dr. Yasmin.

Evaluate the way politicians and health officials handled the crisis, identify lessons learned, determine whether survivors still live with the stigma of infection and explore what it means to return to “normal,” suggested Dr. Yasmin.

Her own expertise really took off when covering the Ebola crisis from 2014-16. Her follow-up stories offer a framework for other reporters, including “Why Ebola survivors struggle with new symptoms,” for PBS NewsHour, and “A Woman Survives Ebola but Not Pregnancy in Africa,” which was published in Scientific American.

Additional links

- Committee to Protect Journalists, “CPJ Safety Advisory: Covering the coronavirus outbreak”

- World Health Organization, Live updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Scientific American, How to Report on the COVID-19 Outbreak Responsibly

- Poynter, AP Stylebook tips on the coronavirus

- The Open Notebook, Tipsheet: Covering the Coronavirus Epidemic Effectively without Spreading Misinformation

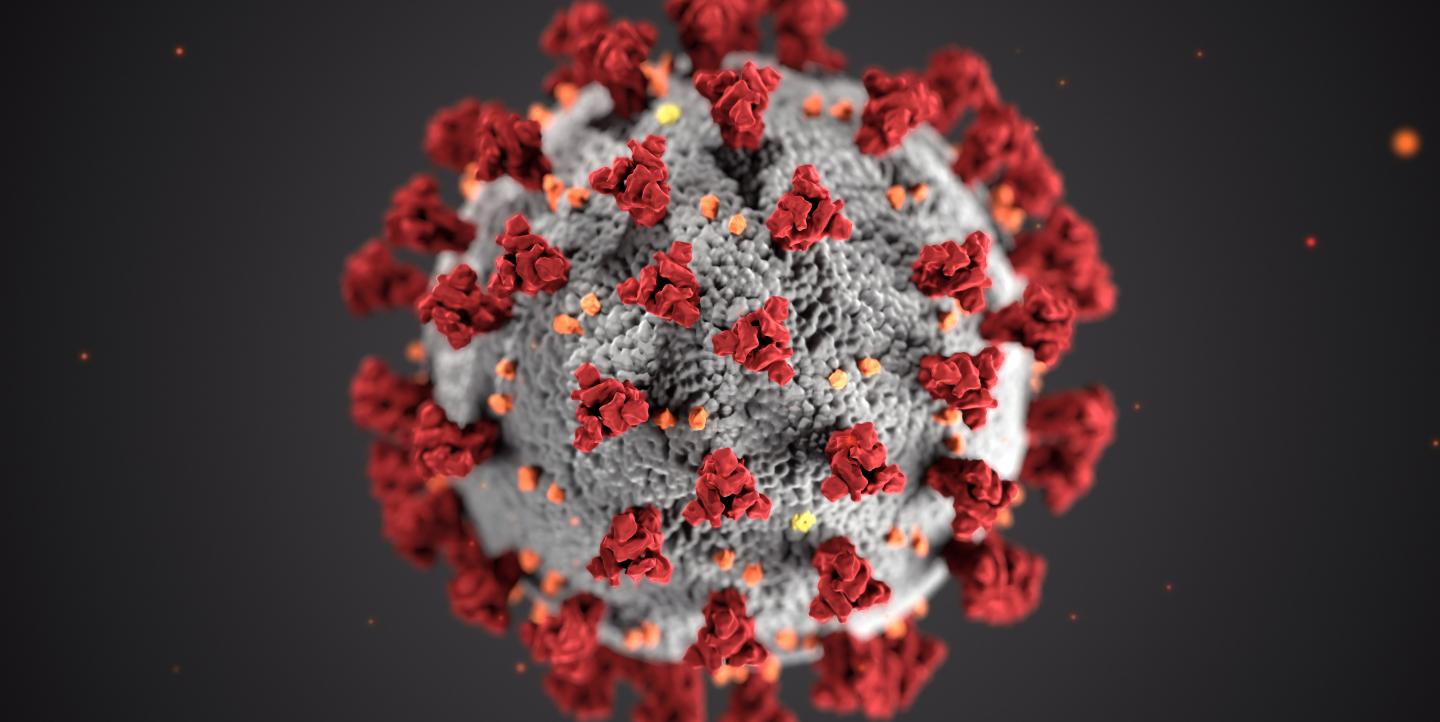

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via CDC.

This article has been updated to reflect the World Health Organization's announcement on March 11 that COVID-19 is officially a pandemic.