In recent years, media organizations globally have experimented with “gamifying” the news – making it more interactive to engage audiences. The BBC, for one, launched iReporter in 2018 to teach media literacy skills, and Yle News Lab in Finland designed a game to demonstrate to users how false information spreads via social media.

In May, ICFJ brought two Georgian journalists from the news outlet, Mtavari Channel – Tato Gurgenidze, a cameraman with 14 years of experience, and Tea Adeishvili, a TV journalist on the weekly “Post Factum” program, and host of a daily talk show – on a tour of the U.S. for training on game-based learning and animation. Mtavari Channel is Georgia’s primary opposition outlet, and a direct successor to Rustavi 2, a popular former opposition channel that has since taken a pro-government stance after a change in ownership in 2019.

Encroachments on press freedom like this are not out of the ordinary in Georgia today. Despite moving up 12 spots in Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index to 77 this year, journalists in the country continue to face threats and censorship. In early March, protests broke out after the passing of a new law which would require media outlets and NGOs with more than 20% of their funding coming from foreign donors to register as foreign agents. The bill was later withdrawn.

“In Georgia, television and broadcast news are the primary source [for news], and it defines the political agenda of the developments in the country,” said Adeishvili. “Starting in 2018, the government began refusing to cooperate with independent media. They refuse to give us comments, they attack us and they call us agents, creators of fake news, traitors and terrorists.”

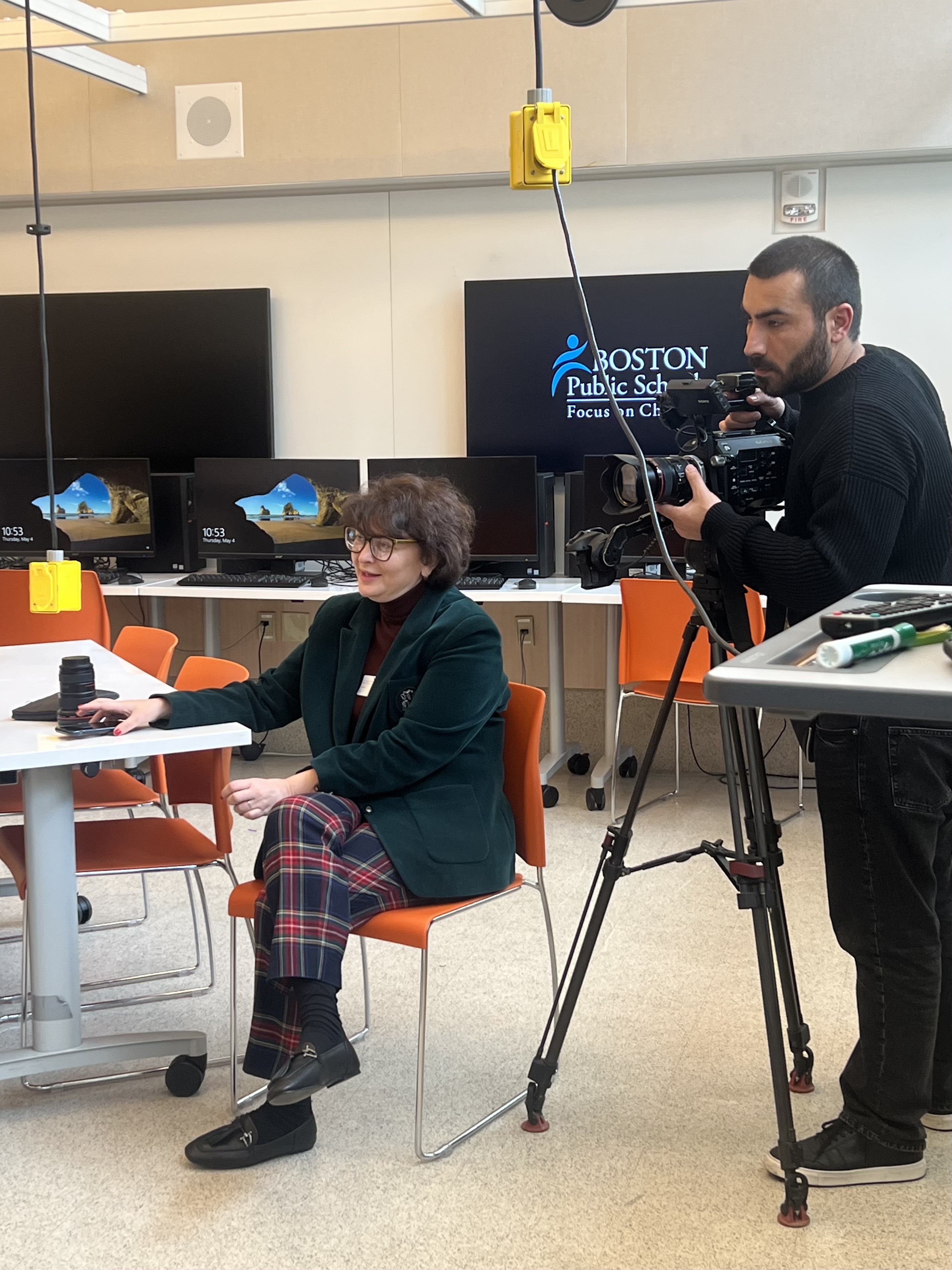

During tour stops in Washington, D.C., Boston and New York City, Gurgenidze and Adeishvili interviewed academics and students about the educational games they’ve created to better understand the opportunities that accompany learning through the use of games. The two journalists will produce news segments on what they learned about game-based learning and animation for Mtavari Channel later this summer.

“This will expand the knowledge of our viewers about what's going on in the field and in particular how gaming is used in education, so that will be informative for us,” said Gurgenidze.

Gurgenidze and Adeishvili spoke with IJNet ahead of their U.S. tour about their reporting, Georgia’s media landscape, the jailing of their colleague Nika Gvaramia, how the war in Ukraine has affected their work and more.

What issues do you typically cover?

Adeishvili: I’ve worked in this profession since 1998. I report on human [interest] stories, features, social problems [and] women's problems. For the last six or seven years, I've worked on analytical and political stories [and] for the last three years, I've covered daily news issues and anchored a daily political news program. I’ve covered some conflicts throughout my career, as well.

Gurgenidze: I work on all kinds of stories, whether it’s politics, culture [and] sports. I even cover some conflicts and war zones.

What do you hope to learn about game-based learning and animation?

Adeishvili: I think [the tour] would be good for my company as a leader in development and transformation [of journalism in Georgia], to use these new technologies not only to increase the size of our audience, but to provide more information and education to our audience in this field, as well.

Gurgenidze: [The tour] will allow us to introduce the best practices [for game-based learning] in the U.S. to our audience.

Adeishvili: Sometimes [our audience] thinks that everything has been accomplished in the universe, but [this opportunity will show them] that there are still some chances [to learn something new].

Gurgenidze, previously you worked for Rustavi 2, which used to be Georgia's most popular independent broadcasting company. How did the government's actions affect the station's status?

Gurgenidze: I would start by saying that now I work for Mtavari, which is the main opposition channel and [when] translated [it means “main channel”] literally. It’s the same as working for Rustavi 2, only the name is different.

But as for Rustavi 2 it has changed dramatically. With some of these stories [they produce], you can feel that the policy has radically changed [and that] they are more loyal to the government.

With the government labeling independent media as “fake news” and traitors, does that influence how much audience engagement you get?

Adeishvili: Yes, but our audience is [still] growing. But it also increases the aggression coming from the authorities and then it transforms the reactions and attitudes of their supporters. Then their supporters [start] using these same labels. They've [even] created some social media pages dedicated to criticizing us and attacking our personal lives.

Gurgenidze: And we don't only mean our [station], but other stations and media organizations that have different opinions like TV Formula.

With certain issues such as LGBTQ+ rights or religion marked by a strong sense of social tension, how does that influence your coverage?

Adeishvili: We don't care what sexual or religious minorities individuals represent. We're all human beings, and we cover these issues as usual. [However], sometimes we are blamed or accused of using propaganda to support these ideals.

On July 5, [2021] during Pride, the government cracked down on protesters and as a result, one of the cameramen died and 52 journalists were injured.

After the opposition journalist and director of Rustavi 2, Nika Gvaramia, was jailed last year, did it change how you approached your work?

Adeishvili: A lot has changed. The environment is less stable. Not only in our company, but the entire media environment has changed. One of the reasons [Gvaramia] was jailed was because the government didn't like how he was covering the issues.

Gurgenidze: He was also giving guidance [to other journalists] and [telling them] the tone [they should use] and how to behave, how to cover developments. This is why they didn't like him.

Adeishvili: The article [of the law] they used against him when they charged him has never been used against any media representative in Georgia. He was accused of using a company car for his family, so he was sentenced to three and a half years [in jail].

How has the war in Ukraine affected your work?

Gurgenidze: I was in Ukraine right before the war and stayed over there for some time during the war. I [already] knew the atrocities of Russia, the occupier, but I saw it firsthand, and then I realized the power of this occupying force. I have confidence and hope that when Ukraine wins, it will be a victory for my country too.

Adeishvili: I gained some additional confidence and belief in what we are doing, and that we are on the right side of history. This also increased the belief that fighting for Ukraine is also fighting for your [own] country. There are Georgian fighters in Ukraine, and they believe that they are doing this for Ukraine and for Georgia too.

Support is primary for us because we understand that they [would] do the same for our country. We are looking forward to the victory of global democracy and civilization, and the victory of Ukraine.

One June 22, 2023, Georgia's President Salome Zurabishvili pardoned Gvaramia. The article was updated on June 23 to reflect this development.

The interview was translated by NaNa Kiknadze and it was edited for clarity.

This was made possible through the generous funding of the U.S. Embassy in Tbilisi, and the views expressed in this article are not representative of the opinions of the U.S. Mission to Georgia.