Editor’s note: Jelter Meers is the Pulitzer Center's research editor. Read the original report here.

Environmental damage reports often focus on economic activities, such as illegal fishing by unregulated fleets, deforestation in protected areas, or oil drilling projects without the appropriate licenses.

Through the Pulitzer Center’s environmental reporting networks—the Rainforest Investigations Network and the Ocean Reporting Network—we aim to uncover not only these types of wrongdoing, but also the financial structures behind them.

There are many money flows involved in any environmental crime. We have developed different methodologies to uncover them, adapted to the region, jurisdiction, and industry.

In the Congo Basin, for example, Rainforest Investigations Network Fellow Didier Makal got a list of ten mining companies that received licenses to mine in the Haut-Katanga and Lualaba regions of DRC. To begin, we looked for their registry numbers, incorporation dates, addresses, and management and ownership information.

By looking at each manager and owner, we established links between the different companies, found that some of the owners also own companies in Europe, and that one of the shareholding companies was owned by Swiss mining giant Glencore’s Canadian branch.

In this methodological series, the Pulitzer Center’s Data and Research team explains investigative strategies for uncovering the three main money trails (ownership, investment, and supply chains) and the mechanisms behind them, including examples of creative research that helped us overcome stumbling blocks.

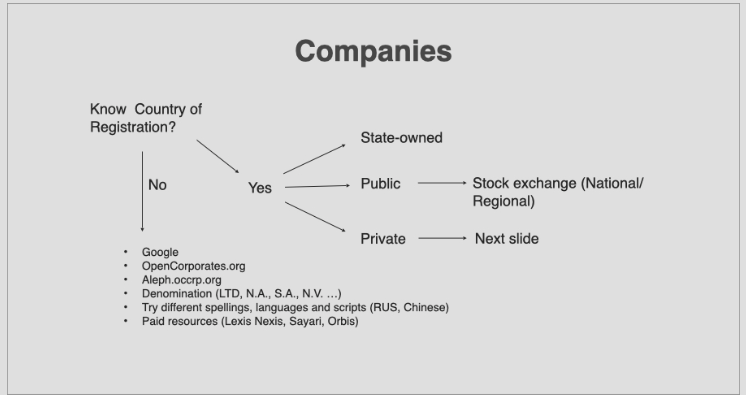

We usually start by trying to find out who owns the companies, land, and other assets, like an airplane or truck, involved in environmental destruction. Starting with companies, we need to distinguish between the different kinds of companies.

- A publicly traded company will have its shareholder and financial information on a stock exchange or regulation website, and usually on its own website. It wants to inform its shareholders about the company's health. Hence, you need to take their reports (even when they are audited) with a grain of salt.

- As its name implies, a state-owned company is owned by the state. However, the state is often not the sole shareholder, so it might be worth trying the steps we would use for a private company to uncover the other owners.

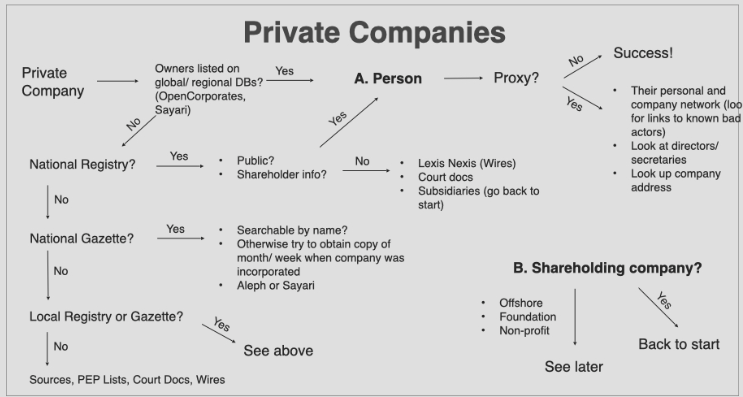

- Private companies come in all shapes and sizes when it comes to their ownership structure. Different types and sizes of companies have different requirements when it comes to disclosing and filing information. This will influence how much information (like ownership) you can find about a company.

There are different ways to learn more about a private company depending on its structure. All have different denotations and varying reporting requirements, depending on their country. Our research toolkit series gives a more detailed breakdown to how we access corporate information for each type.

To look into private companies, we use company registries and international company information databases like Sayari. This is a paid database option for accessing updated worldwide company ownership information.

Sayari is helpful in uncovering international business networks because it shows if a manager or owner of a company is also involved in another company (even in another country). Whereas most company registries only allow you to search by a company name, it allows you to look up a person's name to see what entities they are involved in.

Another good starting point is to verify the existence or legal name of a company. Through the free database OpenCorporates, you can find basic information such as the address, registration date, and industry of the company. Depending on the jurisdiction where the company is registered, you may also see who manages or owns it. You can also look for a person’s name using the “Officers” search function, but it’s not likely you will find all the companies in which the person is involved.

The next step is to go to the company registries themselves. Countries or jurisdictions may require a company to register itself to engage in economic activity. Many countries have registration information available online, and OpenCorporates often provides their hyperlinks. The amount of information you get, how you can search for it, and how much it costs depends on the country. Another critical factor is the size of the company. Smaller companies can submit abridged financial accounts to the registry, apply to be exempted from an audit, and don’t need to submit director’s reports.

In some company registries, you can only search by company number, and not by name. OpenCorporates comes in handy because it displays basic company information like numbers.

Some registries, like those in the UK and Belgium, provide ownership information and original documents for free. This is the best-case scenario. You can use the indexed data on the websites or review the original documents. Important files are the incorporation filing, annual (or full) account, and confirmation statement. The content differs per country, and some national registry websites can be hard to navigate. It pays off to spend time exploring the websites and documents.

Some jurisdictions don’t have any online database or ones that will only let you verify a name, like the UAE. Most online registries are somewhere in between, with paid downloads or subscriptions and a variation on what the information contains. If the online information does not include ownership, you can try your luck requesting the original incorporation documents, which sometimes mention the founders.

Many countries have periodical publications that register company registrations and ownership changes. These national or business gazettes are good for cases where a national registry is unavailable.

If the company jurisdiction doesn’t have a registry of gazettes online, you can still try your luck with leaked information, which you can access for free. The ICIJ’s Offshore Leaks and OCCRP’s Aleph are good examples. Court documents, Politically Exposed Person bulletins, and State Department Cables can also contain information about a company's ownership.

The fact that a country has no online database or publicly available company information can be an indication that it is a secrecy jurisdiction and that the company was registered there with the purpose of hiding the ownership.

There are still other avenues to try if you get stuck. For example, use Google’s advanced search functions to look for slideshows (filetype:ppt) or PDFs (filetype:pdf) uploaded by the company at conferences or on their website. People may also list their relationship to a company on LinkedIn or other social media. This type of evidence may not hold up against fact-checking requirements as well as original company registration documents.

Photo by Shane McLendon on Unsplash.