Editor’s note: Bram Ebus was a 2022 fellow of the Rainforest Investigation Network (RIN), an initiative of the Pulitzer Center. Read his reporting here.

A team of 37 journalists and media professionals from 11 countries worked together for 16 months to produce Amazon Underworld, a data-driven and cross-border investigation that gained insights into armed groups and illicit economies in the border regions of six Amazon countries.

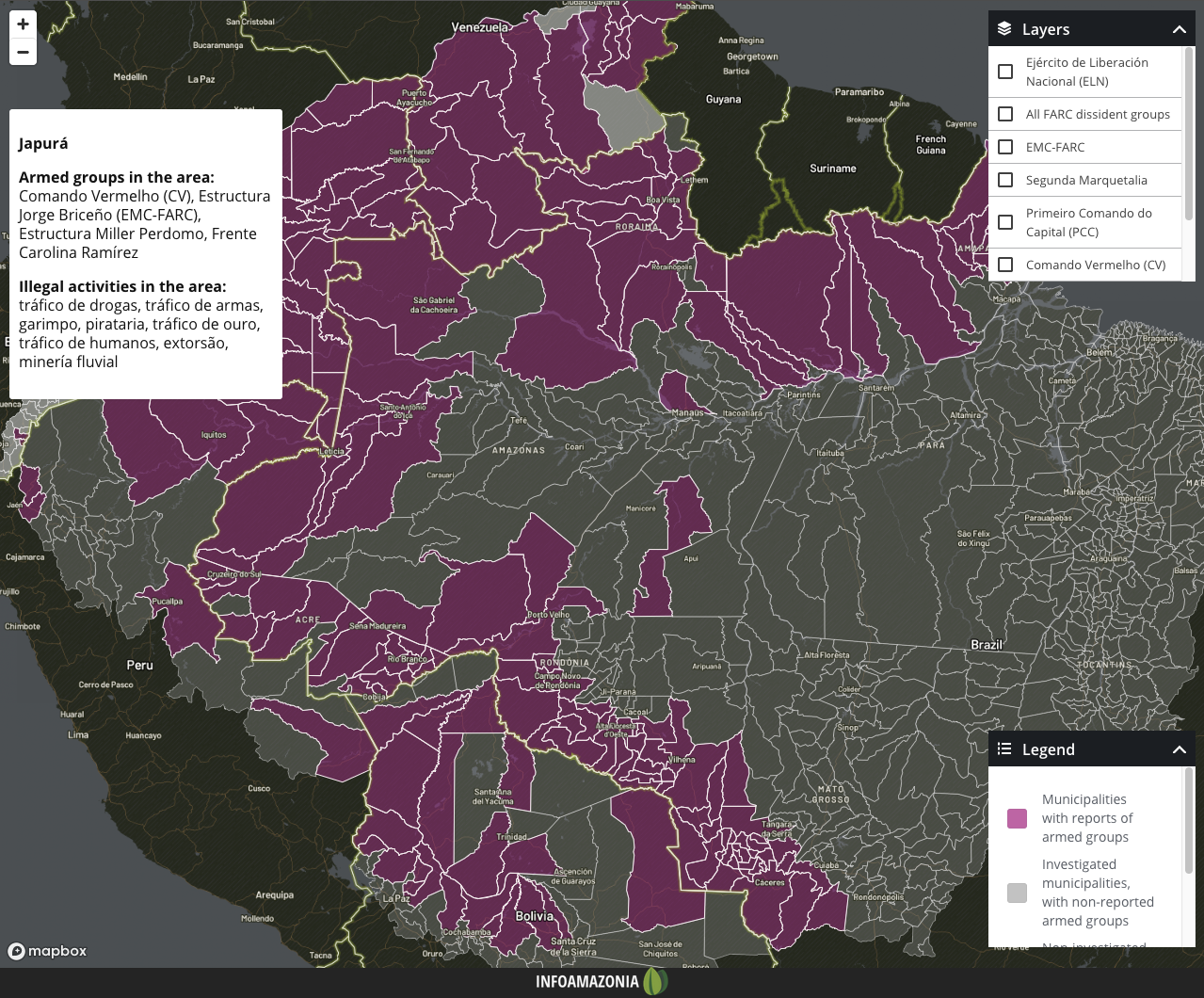

We created an interactive map of armed groups in the regions, and a series of in-depth reports on various aspects of the region’s criminal enterprises, many of which have received little or no media coverage.

This investigation was also published by InfoAmazonia in Brazil, La Liga Contra el Silencio in Columbia and Armando.info in Venezuela. The database and map, built by data collected through quantitative and qualitative methods that cover 348 municipalities in six Amazon countries, are being used by NGOs and other media outlets to plan their fieldwork in a secure manner.

A screenshot of the Amazon Underworld interactive map. Credit: Amazon Underworld

Here are some of our strategies and methodologies to complete this ambitious and high-risk collaborative project, as well as lessons learned.

How to collaborate across borders

Four elements were key to coordinating the collaboration across six countries with different languages, currencies and project management styles: listening, fostering trust, planning, and embracing flexibility. Importantly, country-region conditions strongly influence our fieldwork, and understanding these is crucial for the success of the research and the safety of journalists. For example, we needed to know if a drought affected a specific river crucial for navigation, how armed groups are present in the region and their ties to authorities, and which sources and local actors can be trusted in case of an emergency.

Photographer Andrés Cardona and journalist Bram Ebus travel the borderlands of the Brazilian-Colombian Amazon to document illegal gold mining operations. Credit: Alex Rufino

How to gather information in a region as big as the Amazon

One of the most significant challenges of working in the Amazon is accessing sources in remote areas and obtaining reliable information. We had to build our reporting strategy with information such as the location of health centers or airstrips for exit routes.

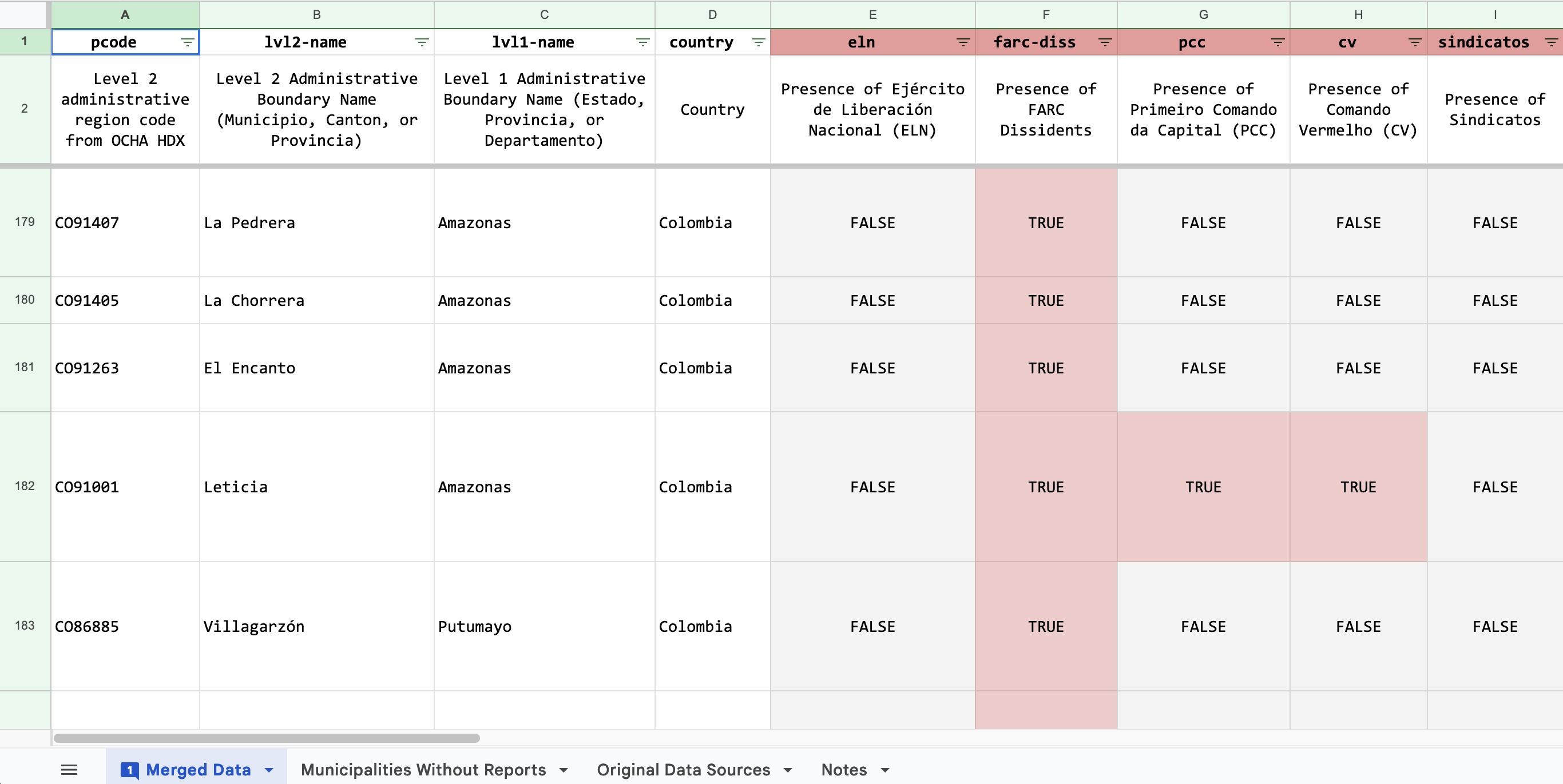

To collect information from a region larger than the European Union, with limited roads, urban centers, and digital connectivity, we submitted hundreds of requests for access to public data and spent months creating the armed groups database using Excel and Notion. This database, compiled transnationally with a uniform methodology, relied mainly on primary sources, including local interviews in the field or by phone and official documents, especially from the executive and judicial branches of each country.

Given the potential bias in politically motivated or poorly researched documents by state institutions, these sources were thoroughly vetted and approved before being added to the database.

A screenshot of the collaborative database compiled transnationally with a uniform methodology.

Credit: Amazon Underworld

How to investigate illegal mining barges

The objective of one of our reports was to identify the number of mining barges, which are metallic beasts that scoop up river sediments rich in gold and process them with the toxic quicksilver mercury. We focused on the Puruê River in Brazil, which originates in a national park in neighboring Colombia.

For our reporting, it was crucial to count the number of barges, allowing us to estimate environmental damage, gold production, and the illicit revenues of the Colombian guerrilla and corrupt Brazilian police officials, who both receive a cut. Initially, we attempted to develop an algorithm with the assistance of the Pulitzer Center and Earth Genome. But this did not work because of persistent cloud coverage and the risk of double counting because of the mobility of barges.

We forged a partnership with an NGO working on Amazon protection and scheduled two piloted flights and counted a total of 168 barges. This raised questions, considering that just a month prior, a targeted crackdown by law enforcement allegedly destroyed a significant number of them.

Using satellite imagery from Planet, we noted a shift in the river’s color, which had been a light brown, similar to coffee with milk, for years due to intense dredging. Approximately five days before the crackdown, the river reverted to its original blackish hue, signifying the cessation of barge activity. When talking to locals, including miners themselves, it became evident that they had managed to conceal most of the barges in anticipation of the crackdown. When we conducted the follow-up aerial survey several weeks later, the number of barges drastically increased as the miners were back.

During a fly-over in early July, 159 mining dredges were observed along the Puruê River.

Credit: Jaap van 't Kruis

Security approach

When the project kicked off, one of the team's initial meetings was a fieldwork security workshop aimed to prepare teams by learning how to analyze context and identify risks, establish protocols for physical and digital security, and respond in emergency situations.

Police in Barcarena search a suspect during a nighttime patrol. Credit: Wagner Almeida

All reporting trips to Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela were monitored, and security protocols were designed before each mission. These protocols included contextual information about security conditions such as the presence of illegal armed groups, communication possibilities (cellular signal, data access, etc.), key contacts for emergencies, and details of places and individuals to interview in each location. We understood that the plan on paper could change, but it served as our secure foundation for work. We pre-established the frequency of calls or messages to report everything was okay or inquire about any updates.

Rivers in southern Venezuela are used as trafficking routes for fuel and other mining supplies.

Credit: María Ramírez Cabello

Among the tools used for monitoring and communication was a Garmin GPS device in each country. It helped monitor routes, locate teams in established places, and provide brief reports via phone numbers or emails on-field progress. It also facilitated sending and receiving alert messages.

An incident occurred on the Puruê River in Brazil near the Colombian border. When the team was navigating the river, they were confronted by a group from the Japurá Military Police, who seized devices storing photos and videos.

Upon being alerted to the situation, we immediately activated the agreed-upon protocol and reached out to trusted contacts who assisted us, within hours, in notifying the authorities. The same day, our team was approached again by the Military Police, who returned the seized devices. Monitoring continued, and check-ins with contacts became more frequent to closely follow the situation, which ended without further incidents until the team returned to Colombia.

This story was originally published by the Pulitzer Center and republished on IJNet with permission.

Photo by Renan Bomtempo via Pexels.