Since 1992, at least ten South Sudanese journalists have been killed while reporting, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, with the most common cause of death being murder.

“If you want to die early in South Sudan, join the media profession,” said journalist Adia Jildo during a MDI Media Award Ceremony in Juba.

South Sudan ranks 128th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, with journalists facing censorship, threats and intimidation, unlawful arrest and death. In addition, journalists undergo trauma from reporting on ongoing violence, and are often unable to afford psychological support due to low wages.

As a result, many journalists have joined NGOs and the private sector in search of better pay and safer work environments, hollowing out the already-struggling media space in the country. The threats facing journalists at Eye Radio, an independent USAID-funded radio broadcaster and online news source in Juba, is emblematic of these obstacles to press freedom in South Sudan.

Risks to journalists in the country

Oliver Modi, a journalist and the former head of the Union of Journalists of South Sudan said that the situation of media practitioners in the country is dire. He highlighted a case from January 2015 when “five journalists were shot, attacked with machetes and set on fire in an ambush in Western Bahr el Ghazal state. ”In March 2022, former Eye Radio editor Woja Emmanuel Wani was kidnapped in the capital city of Juba, tortured and poisoned before escaping,” he added.

“I was put at gunpoint and forced into the car,” said Wani. “They drove me to an unknown location where they questioned me on issues related to politics and then drugged me.” Emmanuel still does not know the identities of his abductors.

Threats also include arrests and detainment by state security. Award-winning journalist Charles Wote Jordan, Eye Radio’s “Dawn Show” producer, describes South Sudan’s media space as “horrific.” While reporting in February on the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of Conflicts in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), the main tool governing the country, Jordan was arrested alongside other journalists at the National Parliament.

“The environment isn't fair when it comes to covering issues that [concern] the [R-ARCSS],” he said. “Even when there was a media invite, the security at the parliament still came and said we weren't supposed to be here. And they detained seven of us for hours but we were later released without any clear reason stated” as to the reason for the arrest.

Censorships and closures

In addition to direct threats against its reporters, Eye Radio has also faced threats of closure and censorship as an organization.

“Due to threats and other major challenges, there is censorship. We even censor ourselves, mainly because we are laying a foundation in South Sudan,” said Koang Pal Chang, Eye Radio’s station manager, in reference to the relatively new presence of independent journalism in the country. "In addition to censorship, other obstacles include a lack of access to information and a need to develop professionalism in reporting," said Chang.

In 2016, Eye Radio was temporarily shut down by South Sudan’s National Security Service for airing an audio clip of opposition leader and current First Vice President Dr. Riek Machar, who was then living in exile in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.

“The National Security Media Desk asked us why we did not credit the media house we picked the clip from. I remember they said, ‘if you were in an opposition-controlled area, would you play the voice of President Salva Kiir?'” said Koang. It took two weeks of lobbying by the station and its two million followers to get the show back on air.

Six months ago, Eye Radio faced more censorship as it was forced to apologize for a story it ran deemed critical of the government. The media house interpreted a quote by information minister Michael Makuei, who stated that “South Sudanese are fed up with us,” as “South Sudanese are fed up with their leaders” — a translation that Eye Radio was pressured to apologize for or risked being shut down.

“What happened recently is beyond journalism,” said Koang, who attributed the forced apology to the minister’s personal dislike of Eye Radio. “Some of us even refused to support the apology decision, but we had to [apologize], considering how many South Sudanese need the radio.”

Chang said the future of press freedom in his country is still dark, and though there are organizations who do stand for journalists, such as the Union of Journalists of South Sudan, Association for Media Development in South Sudan, South Sudan Press Club and the National Press Club, much more needs to be done on a governmental level to improve the state of media in the country.

“Media investors and various stakeholders need to continuously insert more efforts on [informing] authorities of the importance of media in development,” said Koang.

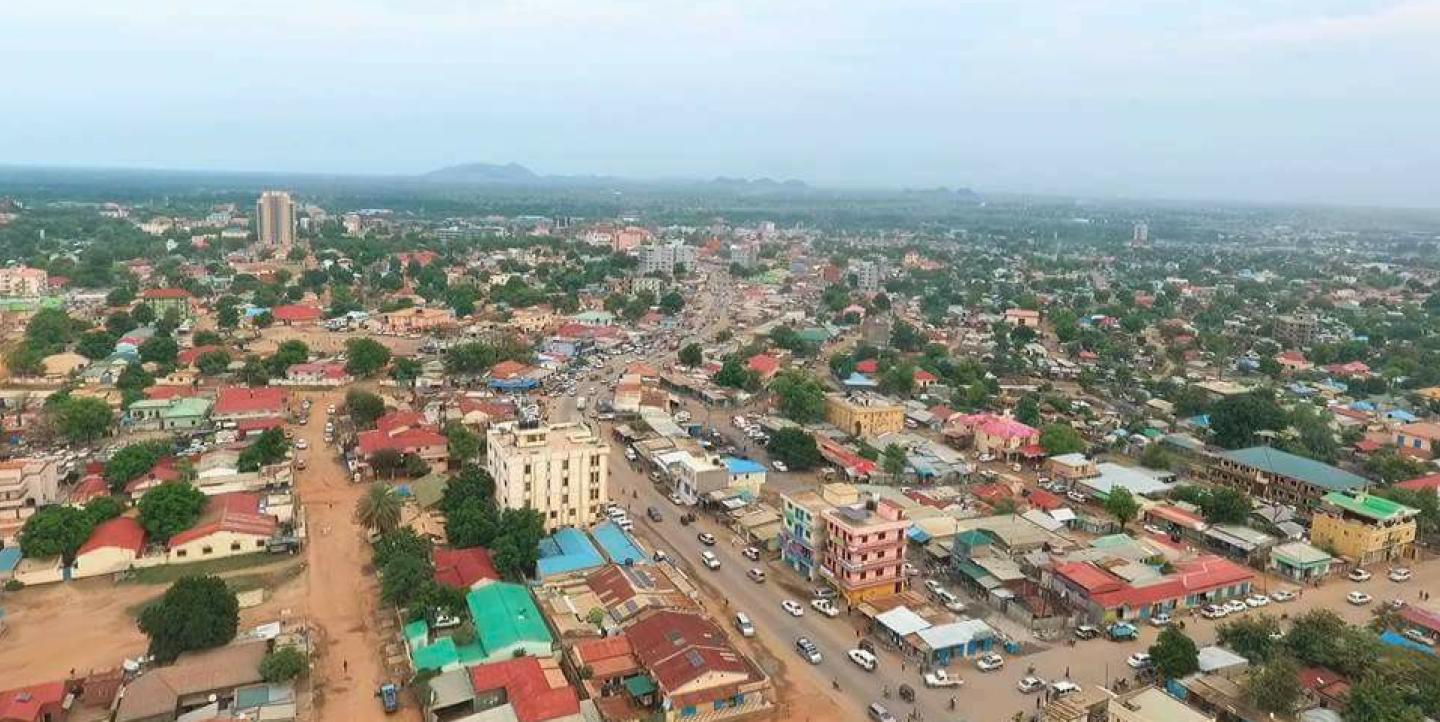

Photo courtesy of D Chol via Wikimedia Commons.