What if we thought about journalism and reporting stories from a different point of view? If we approached it like a collective construction, where different threads come together to create something new?

“We are weaving a basket of abundance, of wisdom. We are weaving as a community, from the point of view and feeling of the territories,” said Cindy Amalec Laulate Castillo, an Indigenous woman from the Tikuna community in Colombia, referring to the work she does as part of Agenda Propia’s collaborative storytelling network, Red Tejiendo Historias.

Like Laulate Castillo, Indigenous media outlets and newsrooms that collaborate with Indigenous communities offer unique perspectives on how to report stories about their communities, and how to do journalism in general.

I spoke with four media outlets in Latin America to learn from their experiences covering Indigenous communities. Here are some of their ideas to rethink how we cover the topic, how we relate to our sources, and how to reach those we report on.

Opening space for voices from Indigenous communities

When Agenda Propia was born, it covered the armed conflict that affected Indigenous communities in the Cauca region of Colombia, like many other media outlets did, said founder Edilma Prada. “But the inclusion of Indigenous voices in their stories was very timid, and there was a historic demand from the Indigenous communities for the narrative about them to be different,” she explained.

Agenda Propia reconsidered its approach. “The idea then was to start weaving with the Indigenous communities, and to change the agenda towards initiatives of resistance and peace of the Indigenous communities.”

Indigenous communicators, editors and designers, were invited to join the team, to tell their own stories. In their reporting, among other efforts, they aim to include voices of women and children in the Indigenous communities, and not just the leaders.

Taking time to understand the context

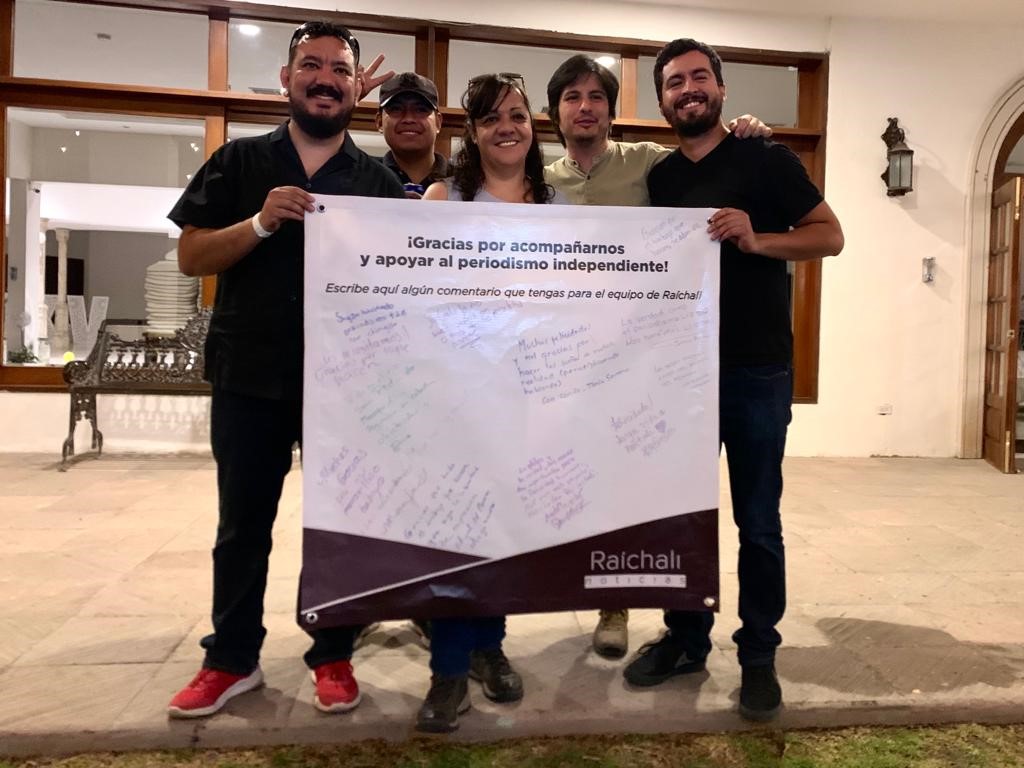

Jaime Armendariz, founder of the media outlet Raíchali (“Word,” in Rarámuri) that reports on Indigenous communities and human rights in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, explained how his newsroom changed its approach when Carlos Fierro, a journalist from the Rarámuri Indigenous community, joined the team.

“Before starting to cover an issue, we have to arrive and spend some time with the community so that they can get to know us, to trust us, and open up to talk about the things that are happening there,” said Armendariz. “As journalists, we sometimes arrive ready to report on an issue, but backed by the beliefs that we have, by our education. This is not always the best, because we might not be understanding the cosmovision of the Indigenous communities.” Thanks to Fierro this practice, continued Armendariz, has changed the way he relates to his sources for other stories, too.

Agenda Propia, meanwhile, holds “word circles” (“círculos de la palabra,” in Spanish), where journalists meet with community members to learn more about the local context and their concerns, before starting a project. “We listen to the others, we listen to the territory, we all listen to each other,” said Paola Jinneth Silva Melo, coordinator of Red Tejiendo Historias.

Working with local journalists

Ruda was created to highlight the voices of women from the Indigenous communities of Guatemala, with a community journalism approach. “It’s a type of journalism done on a daily basis by the people who are close to the issues; they document what happens and with the support of the internet they can publish or share the information with media outlets about what is happening in their community,” said Andrea Rodriguez, journalist and researcher at Ruda. “The person is reporting, but they are also a part of the community. They live the situation they are reporting on.”

Based in Guatemala City, the newsroom editors polish and publish the stories, but the core of reporting is created in the communities. “It’s not just the voice of the reporter, but the voice from the community,” said coordinator Marta Karina Fuentes.

Rethinking formats and distribution

Reporting in and for Indigenous communities is not just about rethinking the content, but also the format. When the Raíchali team created their website, for instance, they wanted to share some of their written pieces in Rarámuri. But after doing a survey to get to know the Rarámuri communities, asking what news they were interested in and how they wanted their stories to be told, they decided otherwise.

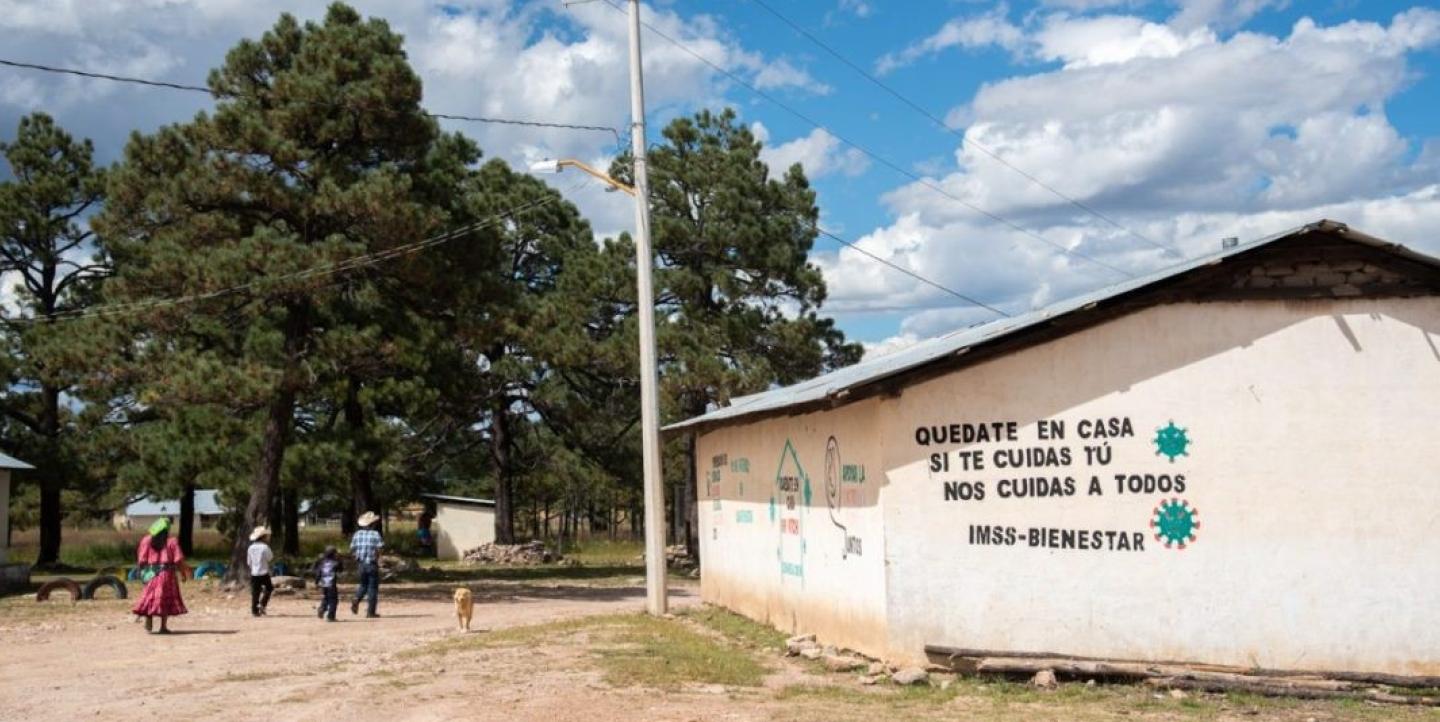

Many Rarámuri speakers can’t read the language, so audio or video reporting in their own language worked better, said Armendariz. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic Raíchali produced a podcast on how the virus was affecting the Rarámuri communities and the prevention measures implemented by the government. The podcast was one of the few sources of information in their own language.

Learning from interactions with the communities, Raíchali also began exploring more visual formats like maps and embroideries as part of their reporting efforts.

Acknowledging your position

Laura Quispe Perez was inspired to launch Telesisa by her own personal experience reclaiming her Indigenous identity while living in Argentina. She and several of her Indigenous colleagues set out to “create content from their own perspective: antiracist, with Indigenous identity, and anti-patriarchal,” she said.

“Journalism from an Indigenous perspective is the activity of generating information with the voice of the people who recognize themselves with their native people or nation,” said Quispe Perez. It’s from that position that they then open up and tell their own stories.

“Doing journalism from an Indigenous perspective is a commitment, it’s a responsibility. It’s to understand that this is a position that is disputed: there are not many Indigenous people providing information,” said Ketzali Awalb'iitz Pérez Pérez, from Ruda. “That’s why for us it’s important to clearly state where we are reporting from, so that they understand how we are going to tell the stories or document what happens in the territories — that we are going to put Indigenous peoples as political and narrative subjects.”

Main image credit: Raúl Fernando Pérez.