In this edited extract from the forthcoming third edition of the Online Journalism Handbook I look at how a ‘triangulation’ approach to sourcing can help broaden story research and improve reporting.

Two centuries ago journalists were called reporters because they drew their information from official reports — documents.

Then in the late 19th century a new source became part of journalistic practice: people, as interviews and eyewitness accounts were added to news articles.

The late 20th century saw reporting undergo another expansion in sourcing, as digital data was added to the journalist’s toolkit.

Although reports had included tables and other sources of data, the properties of digital data — filterable, sortable and searchable — have been significant, and make data a qualitatively different type of source.

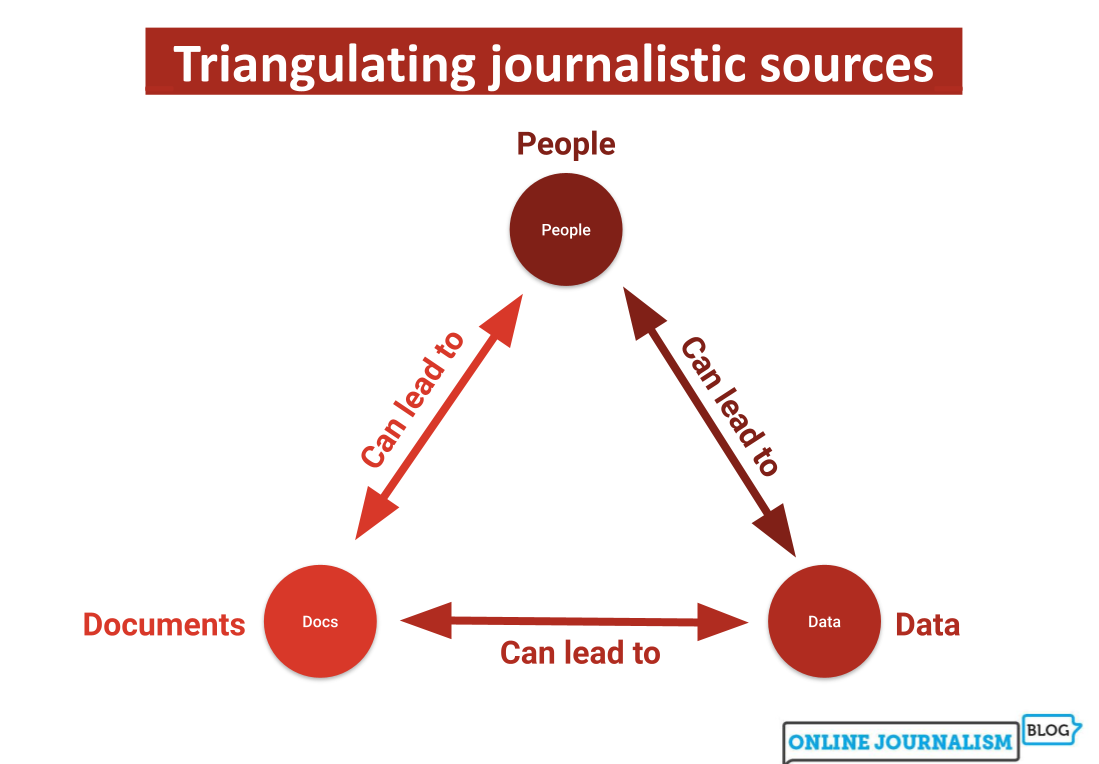

How documents, people and data all lead to each other

Considering sourcing along those three dimensions — people, documents, and data — can be particularly useful when planning sourcing.

It can ensure your newsgathering is original and multi-layered and, in particular, it can help you think about how each type of source can lead to the another:

- Documents can lead you to people: an obvious example would be a webpage (a document) listing contact details — but you might also use a report or presentation to lead you to an expert (the author), or a document about a meeting, or livestream, to identify those people who were present

- Conversely, people can lead you to documents: an expert might tell you about a piece of research, or an interviewee might mention a message they received or a file they saw

- In the same way, people can lead you to data: supplying you with a spreadsheet or pointing you to a table in a report, for example

- And data can lead to people: sorting data to find the biggest or smallest values can help you identify a potential case study, or the place you need to visit to conduct interviews. Data often comes with contact details of someone you can speak to for more context, too

- Documents can lead you to data, too: it might be included in a table or appendix, linked or referred to

- And finally, data can lead to documents: for example, you might take a term in a dataset as a starting point to undertake background research, or use data to direct a Freedom of Information request for documents on a particular problem (e.g. numbers getting worse)

Knowing how to ‘triangulate’ between the different types of source is a key skill for a journalist — it will improve your reporting, and help unlock new story leads.

A social media update is a document, not a person

Considering sourcing along these three dimensions can also help us think more critically when considering different online source strategies.

For example, the World Wide Web is fundamentally a web of documents — social media updates or profiles are documents, not people — and the abundance of these documents has almost certainly shifted sourcing away from the previous reliance on interviews.

Why does this matter? After all, there’s still a person typing the social media update, isn’t there? What difference does it make if their words come via an interview or their social media account?

The difference lies is purpose and control. When a journalist speaks to a person directly, they have some editorial independence to act on behalf of their audience — from negotiating the subject and direction of the conversation, to being able to respond to the answers being given.

They can clarify and check, ask for more details, or challenge where other information contradicts what’s being said.

This doesn’t mean the journalist has total control: the source has independence, too, and may try to control the interview in a range of ways. But the reporter should be able to ask the questions their audience expects them to.

The move from people to (a web of) documents has also moved reporting away from formal and non-public reports to a sourcing environment dominated by informal and public documentation.

This has two implications: firstly, it means the reporter is unlikely to have exclusivity; and secondly, it means that the information has probably been created with a particular objective in mind for that public audience (e.g. to shape a narrative).

Ask what source gaps there are in every story

When working on a story, then, we can ask what source gaps there are in our reporting:

- If it’s based on a public document (e.g. a tweet) then do we have people (original quotes) to flesh that out and give our coverage an original element? Do we need data (or other documents) to put the statement into context or factcheck it?

- If it’s based on people, can we find documents or data that contextualises and confirms — or challenges — what they say?

- If it’s based on data, do we need documents to help us understand it accurately? Can we find people that provide a human dimension to the story?

Thinking in terms of this triangle can help avoid blind spots and the obvious dangers in mistaking one type of source for another.

Paul Bradshaw is the course director of the MA in Data Journalism at Birmingham City University.

This story was originally published on Online Journalism Blog and republished on IJNet with permission from the author.

Photo by Romain Dancre on Unsplash.