As the 2012 U.S. presidential election approaches, reporters will consult public opinion polls to gauge the prospects of President Barack Obama and presumptive Republican nominee Mitt Romney.

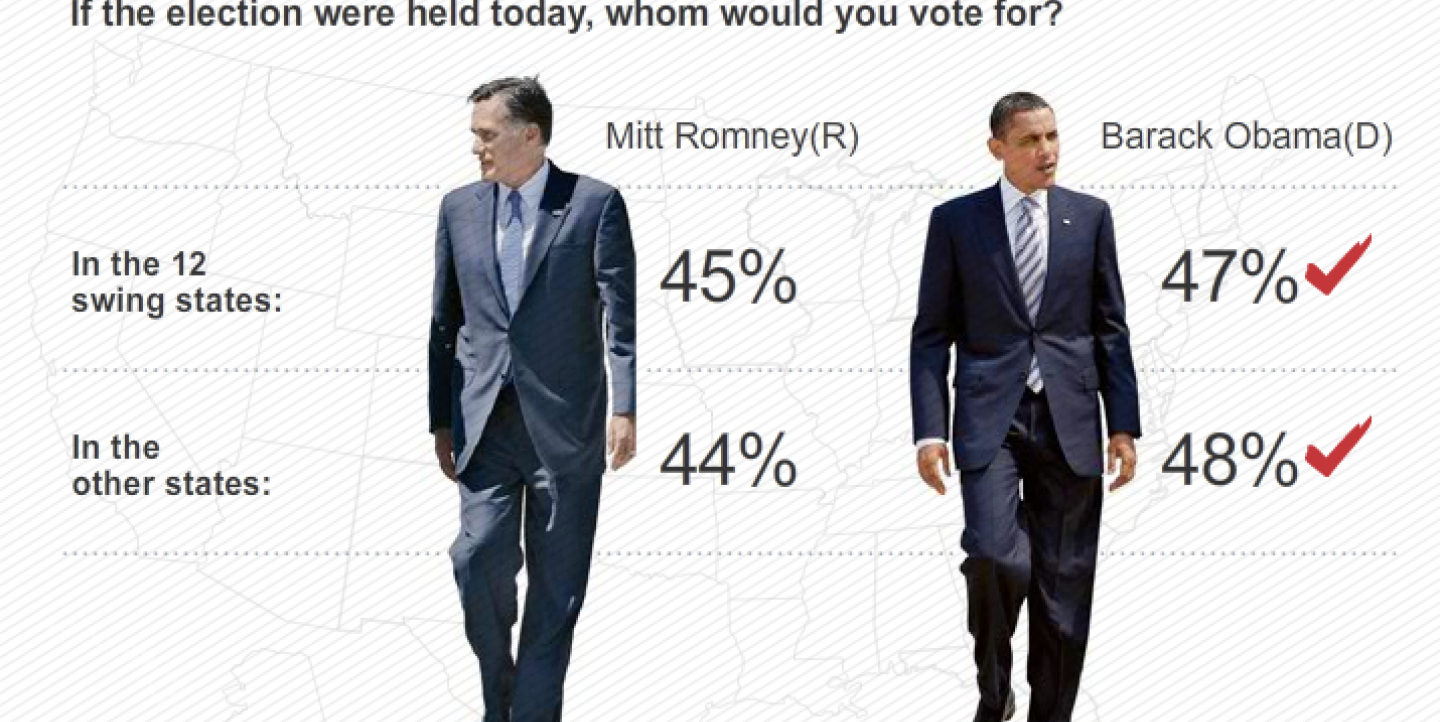

Commentators and news outlets are already speculating on issues including the influence of campaign ads on voters, the weight of swing states and the public reaction to recent policy changes using the USA TODAY/Gallup Poll and the Washington Post-ABC News poll.

But journalists who aren't used to crunching numbers make the mistake of thinking all polls are created equal, says Anthony Wells, associate director of YouGov's social and political polling.

He highlights some mistakes that journalists should avoid on his UKPollingReport blog.

Here are four common mistakes journalists make when reporting on polls:

Trusting "voodoo polls"

Open-access polls were dubbed "voodoo polls" because of their scientific inaccuracy. Typically offered online or by phone, anyone can vote in them and there's no way to tell who they are or whether they've voted more than once. Journalists should report only on polls that use random sampling and quota sampling to ensure that people polled are representative of the population, he says.

Ignoring the margin of error

Generally speaking, the margin of error in polls with 1,000 participants is about plus or minus three points, Wells writes. This means that 19 out of 20 times, the numbers reported in a poll will be within three percentage points of what the actual number would be if the entire population had been surveyed. "What it means when reporting polls is that a change of a few percentage points doesn’t necessarily mean anything – it could very well just be down to normal sample variation within the margin of error," he says.

Comparing apples to oranges

In stories comparing changes in polling results over time, it's imperative that each survey method is properly taken into account, Wells says. Since many factors can influence the outcome, information gleaned from each survey must have been acquired using the same methodology and wording. For example, you can't compare results from a telephone poll to those gathered online, since participants may respond differently in the absence of human interaction than they would to be questioned by an interviewer.

Disregarding sample size

Although reporters should always give more consideration to polls with larger sample sizes, not all polls fit the 1,000-person ideal. Remember that the smaller the sample size, the larger the margin of error and the less accurate the findings are. This also applies to comparing subgroups within a sample, like voters of different age groups. A subgroup of 100 people has a margin of error of plus or minus 10 percent. Polls with fewer than 100 people "should be given extreme caution," and those under 50 shouldn't be used in comparisons at all, Wells says.