Updated at 9:37 a.m. on December 14, 2017

Liberal democracies are being tested around the world by the rapid diffusion of misleading or false information designed to influence voters.

It has happened in France, Catalonia, the U.K. and, of course, the U.S.

Many have proposed — for example, the World Economic Forum — that two of the most powerful vehicles for spreading information, Facebook and Google, should be responsible for filtering out material that is demonstrably false or misleading.

But it turns out that this is not easy to do. False information is often irresistibly appealing and moves too fast to be stopped.

Not an editor, but a scorecard

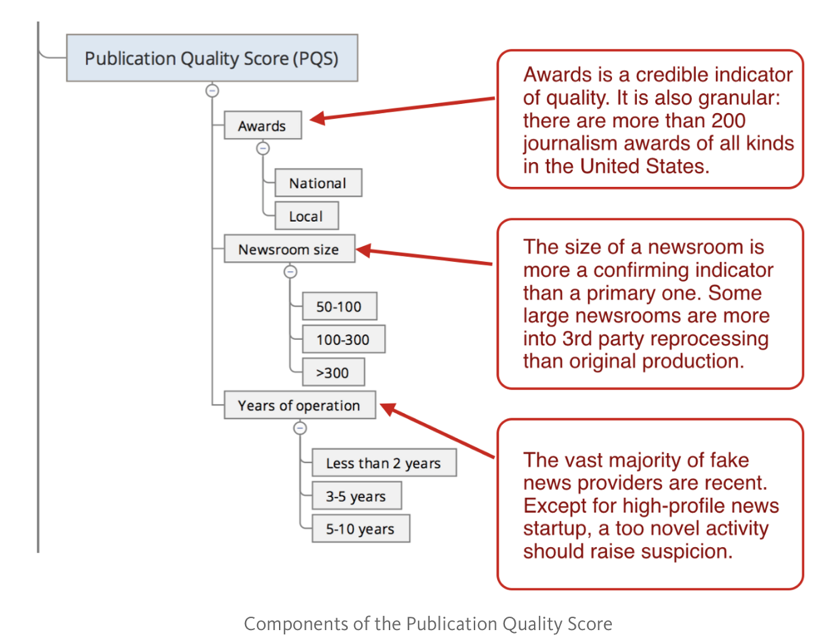

What's more, it is hard to define false news in a way that can be automated by algorithms. Journalist and media consultant Frederic Filloux has developed the News Quality Scoring Project, which attempts to use automated systems to evaluate the likely credibility of a piece of news content. It doesn't label news as false or fake. It simply gives a credibility score based on a series of indicators such as a publisher's or a journalist's previous reliability.

Facebook, Google and Twitter themselves are working with the Trust Project on an automated system to display "trust indicators" alongside information they share with users.

But Filloux himself admits that machines driven by algorithms have a difficult time identifying irrelevant information and evaluating the freshness, uniqueness, or depth of a report.

It takes a village

In other words, human beings experienced in evaluating information need to be involved. And either Facebook and Google provide this kind of human oversight, or outside groups need to take charge.

Wikitribune Campaign from impossible on Vimeo.

One such project is WikiTribune, a news site launched by Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales and driven by 6,000 writers and editors who will write, edit and verify articles about news events.

The need for human involvement in evaluating credibility may also explain why fact-checking websites have become part of the conversation about verifying news.

More and more media organizations are launching fact-checking operations. The Poynter Institute's International Fact-Checking Network is just that, a network of 39 organizations around the world that have agreed to a set of principles of non-partisanship, fairness, and transparency in fact-checking news articles and statements by newsmakers.

Even with all this effort, ideologues and extremists will continue to flood the online world with stories that reflect their beliefs, facts be damned. As Maya Kosoff pointed out in Vanity Fair, fake news has been weaponized by countries and individuals who want to advance their agendas and disrupt others. There is no simple solution.

Perhaps the good news in all this is that the value of experienced researchers, scientists and journalists in evaluating credibility has been reinforced. There is a demand for trustworthy sources, and the supply of providers is increasing. Ultimately, we trust people more than machines. Artificial intelligence is still, for the moment, artificial.

James Breiner is a former ICFJ Knight Fellow who launched and directed the Center for Digital Journalism at the University of Guadalajara. Visit his websites News Entrepreneurs and Periodismo Emprendedor en Iberoamérica. This post originally appeared on News Entrepreneurs and is republished with permission.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via throgers