As journalists from around the world navigate the final weeks of a contentious U.S. presidential election during the COVID-19 pandemic, they could learn a thing or two from their peers in the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

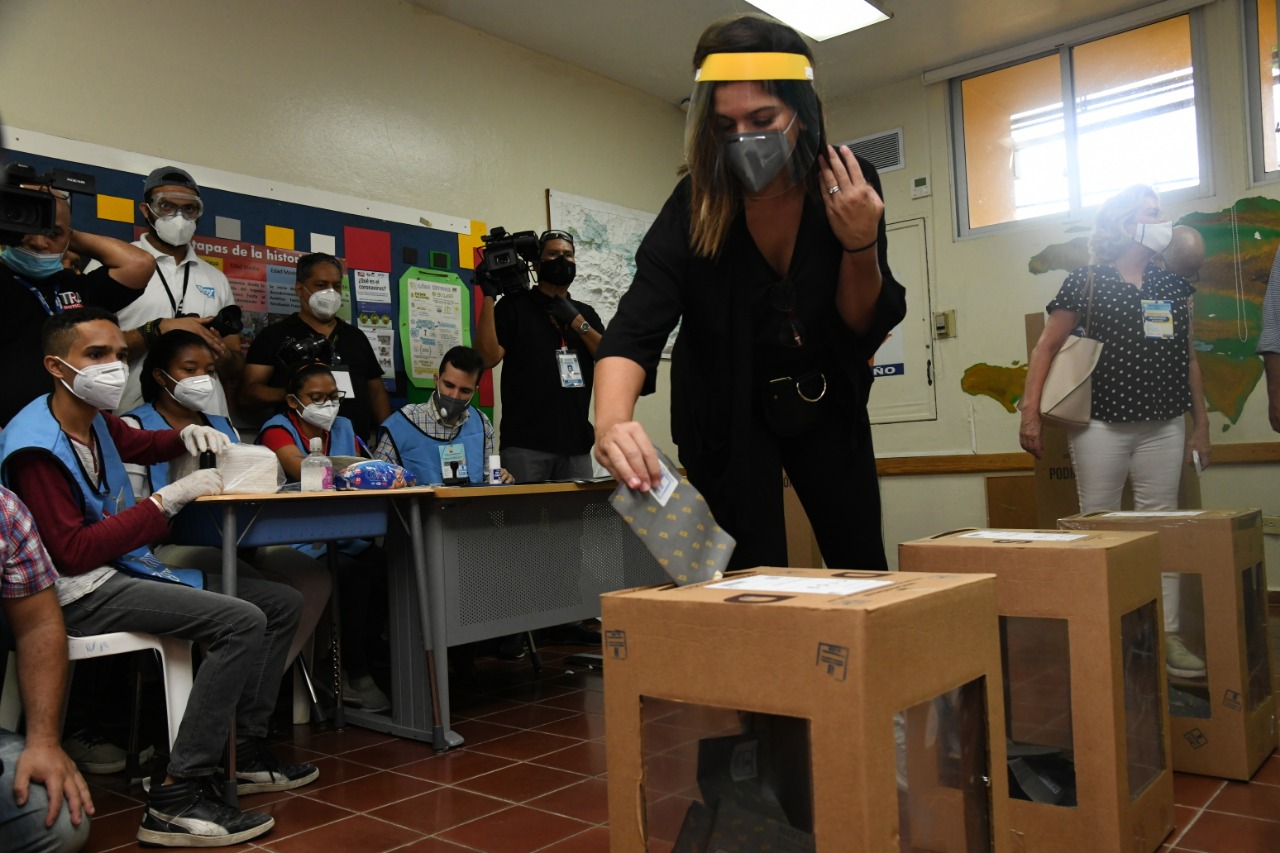

Following its postponement in May due to COVID-19, the Dominican Republic held a presidential election in early July. This was a day after reaching a new record for confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the country.

For Dominican and Haitian media alike on the island of Hispaniola, the election presented significant challenges and opportunities for reporters and their newsrooms. They scrambled to improve safety measures and protect journalists reporting in the field, while adjusting their reporting approaches, navigating newsroom finances and collaborating.

[Read more: How has the pandemic affected journalism? New report offers a sobering snapshot.]

Safety measures

For their election coverage, Dominican newspaper Listín Diario divided its team into two groups: those who would report from home and others who would work in the newsroom.

In addition to social distancing by staff, the newsroom enhanced its sanitary measures. This included regularly fumigating its office space, completely disinfecting the entire building once a week, and purchasing masks and protective suits.

Listín Diario increased its support to employees by holding virtual interviews and editorial meetings, clarifying for reporters when in-person reporting was necessary, and listening to the team to better understand their needs. The newsroom also raised awareness about COVID-19 among staff. “We had to be very emphatic in recommending that they not overexpose themselves,” said chief editor Juan Eduardo Thomas.

Avoiding unneeded exposure to COVID-19 was very important for Mayelin Acosta, a reporter for the newspaper, Hoy. Although Hoy provided its staff with protection and disinfection materials, it was ultimately up to reporters to ensure they followed safety protocols and monitored their own wellbeing.

This extended past the election, as well. “After covering the elections, I was attentive to see if there were any symptoms, and avoided going to the newspaper every day,” said Acosta.

Editorial planning

Another Dominican newspaper, Acento, began to plan its election coverage in January. The team had to navigate not only a state of emergency due to the coronavirus, but also a month-long postponement of municipal elections in February, allegedly due to an electronic glitch.

“We reorganized the team, rethought our work schedules, and then made a plan in which we had to prove that the agility of digital was above any obstacle,” said director Fausto Rosario.

Acento created communication platforms for assigning tasks and updating news. Every reporter had responsibilities, and there was a coordination team comprised of the deputy editor, the editor-in-chief, and the evening and night newsroom coordinator. Like other media, they stopped covering smaller-scale activities they typically reported on in the past.

[Read more: When covering conspiracies and disinformation, avoid adding credibility]

Sustainability

Strained newsroom finances during the pandemic further complicated reporting on the election. In March, for instance, at least seven clients decided to abandon their advertising contracts with Acento.

Luckily, Acento had already been working on new monetization options. Among them was the creation of a crowdfunding option for readers called Colabora con Acento, which solicited donations through PayPal. “COVID-19 pushed us to try that option. And it has taught us a reality: the audience appreciates our work, to the point of collaborating with our sustainability,” said Rosario.

Thanks to the contributions, Acento was able to distribute a special bonus to reporters following their work on the elections.

Citizen journalism and reporting in-person

As the only correspondent for the television show Al Rojo Vivo, Laura de la Nuez works with topics that tend to be out of the ordinary. She often collaborates with journalists at other networks, and relies on videos uploaded to social media to support her reporting.

“Regular people catch the fresh news in a particular town, especially in places where journalists do not arrive quickly,” said de la Nuez. “Videos sent by non-journalists were the ones that helped me to cover the elections.”

When reporting in-person on election day, she advised that journalists should be prepared to navigate large groups of voters, including those who may not be practicing social distancing.

In the Dominican Republic, the country’s Central Electoral Board did not communicate clear information to citizens on how best to maintain their distance when voting at polling stations, said de la Nuez. Journalists were tasked with carrying out their work in less than ideal circumstances while ensuring their own safety wasn’t compromised.

Collaboration

In Haiti, a group of journalists decided to launch Desisyon RD 2020, a program in Haitian Creole, to broadcast the developments of the Dominican elections. This allowed them to identify opportunities for collaboration, according to journalist Ives Marie Chanel.

“It helped us discover the potential that exists for the coverage of binational news and issues. We are talking about coverage by more than 30 radio [stations], and television channels,” said Chanel. “The event also sparked much more interest among Haitians for the Dominican news.”

The initiative brought together outlets and journalists from both Haiti and the Dominican Republic for the first time. Experts on election-related topics also participated, analyzing election results and their impact at the binational level.

For Chanel, collaboration is essential — especially as the pandemic has imposed limitations on common reporting practices. Media in other countries can learn from the Desisyon RD 2020 experience, and collaborate to collect and disseminate information at the local and regional levels during coverage of future elections.

“It makes it easier for us to achieve our goals and sometimes opens up new horizons,” said Chanel.

Indhira Suero Acosta is a cultural journalist and ambassador for SembraMedia in the Dominican Republic. She is a former Fulbright scholar and creator of Negrita Come Coco, promoting popular culture and Afro-descendants. Follow her on Twitter at @SueroIndhira.

Main image courtesy of Listín Diario.