How did major Chinese and U.S. outlets differ in their initial coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic? That’s the central question behind a new study published last week in the Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly journal.

The overall finding: Chinese outlets’ focus on COVID-19 was much more domestic, perhaps because they were focused on trying to contain the outbreak, while the U.S. view was much more focused on politics and the conflict between various levels of government when it came to combatting the crisis.

To arrive at these findings, researchers at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, looked at the three largest newspapers by circulation in each of the two countries. In the U.S., the list included The New York Times, USA Today, and The Wall Street Journal. In China, the newspapers wereThe Beijing News, Caixin Weekly, and People’s Daily. It turned out that these six outlets also represent different ideological views, according to Kaiping Chen, an assistant professor of life sciences communication at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and the senior author of the new paper. “Some are more party-focused in China and some more investigative and we tried our best to cover a variety of mainstream outlets,” she said.

[Read more: What kind of journalism do we need when a crisis hits?]

They also only looked at coronavirus coverage between January and May 2020, to get a snapshot of what early coverage of the pandemic looked like.

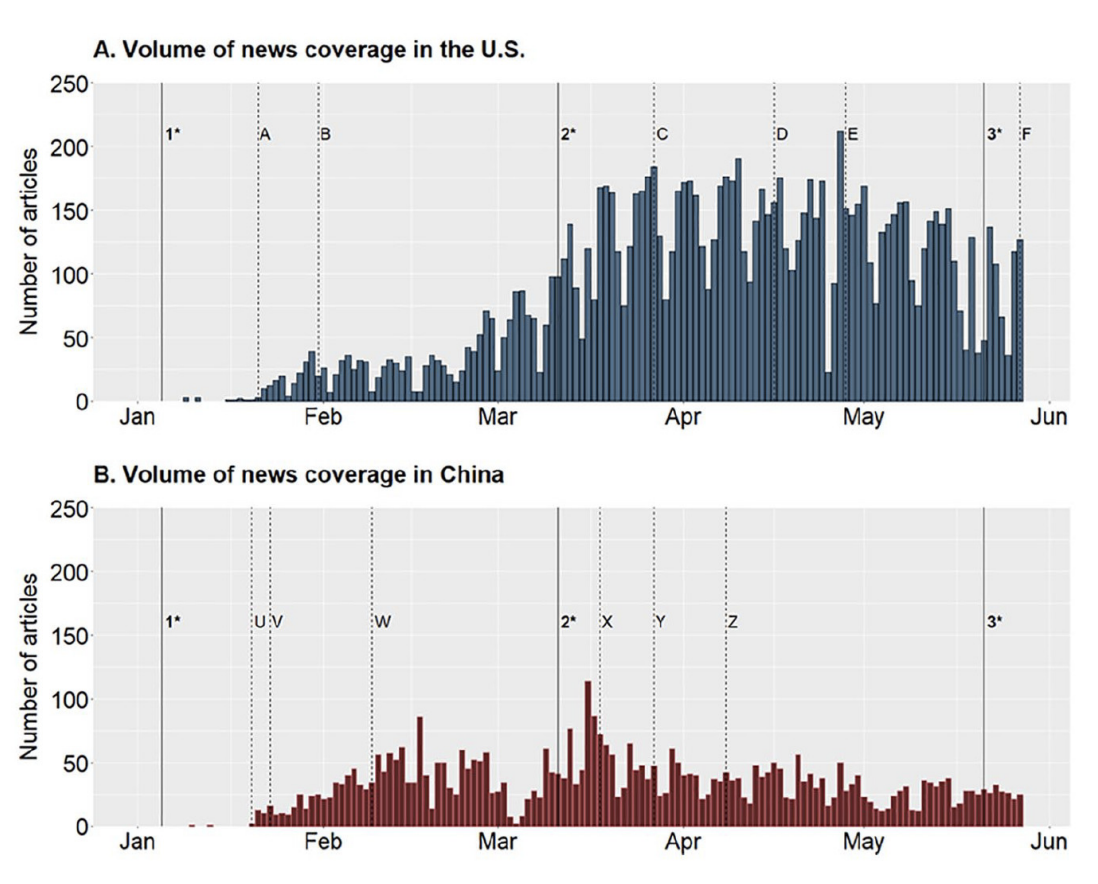

The researchers found that the volume of coverage remained somewhat steady in China, peaking in February and again in March, whereas there was an explosion of COVID-19 coverage in the U.S. beginning in March (around when the crisis was declared a pandemic) that was sustained through the end of the study duration. It speaks to the different pandemic experiences for the two countries, Chen said, where cases in China were sporadic later on. “But in the U.S. at that time, the pandemic was [still] going on,” she added.

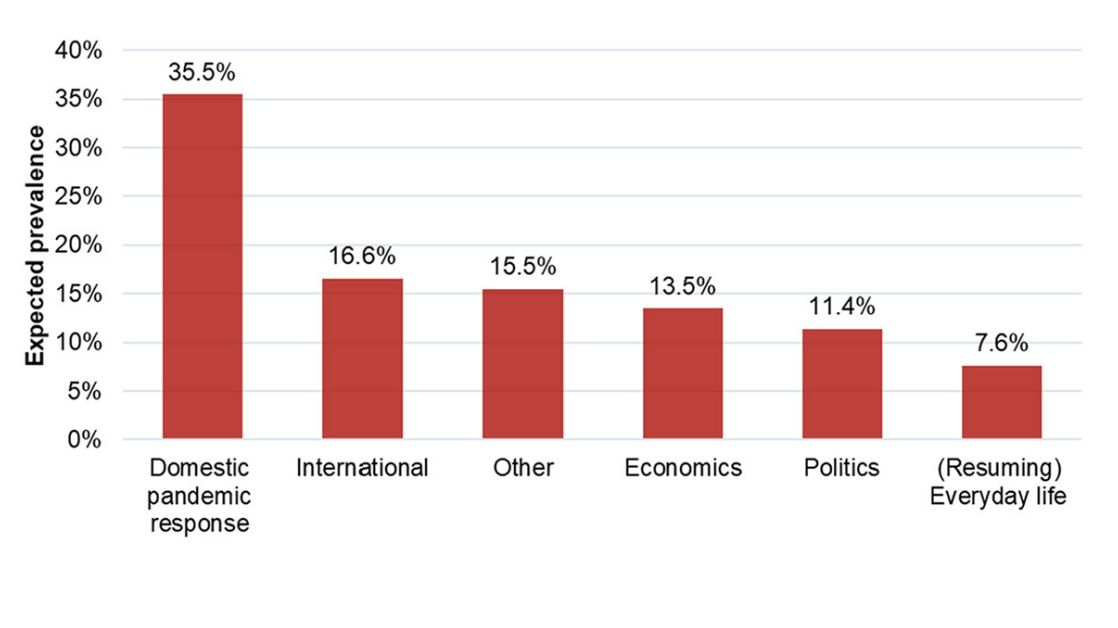

They also looked at the themes of coverage in both countries. In China, coverage was overwhelmingly focused on the domestic pandemic response — especially how different groups were coming together to handle the crisis — followed by international response to the pandemic. And while some of this international coverage focused on how other countries were focused on battling the coronavirus crisis, much of the focus was on international cooperation and how countries were helping each other with medical and other aid for response efforts.

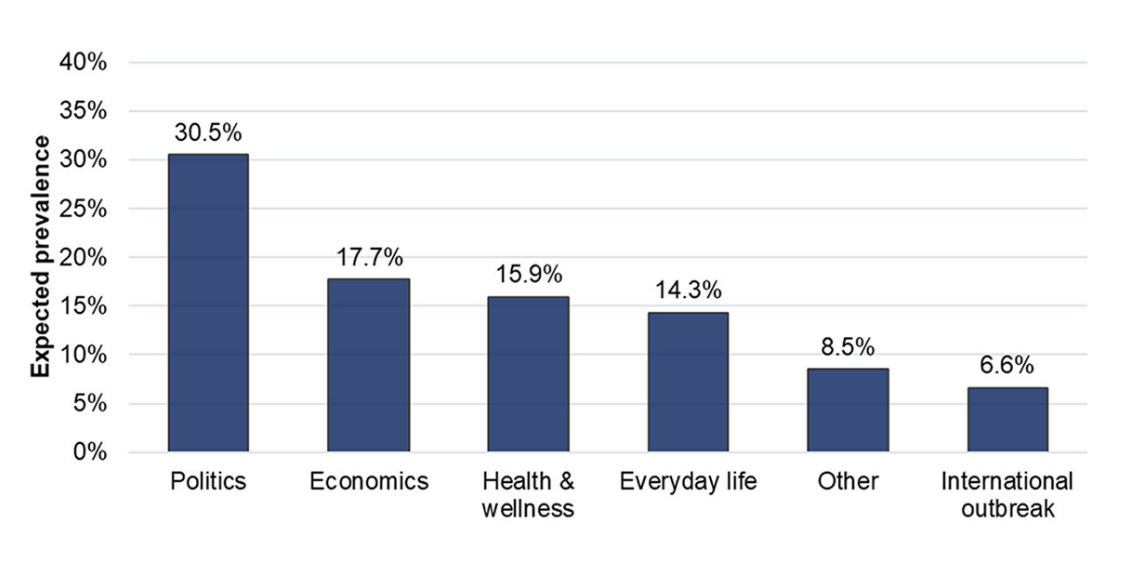

In the U.S., the news scene looked different. Politics, especially centered on conflict between different political entities, was the main focus. Stories focused on the conflict between the White House and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, for instance, or between conflicting guidelines issued by various government figures.

Other differences that emerged were how news stories in the two countries focused on how COVID-19 was impacting society. In the U.S., stories tended to focus on everyday life, with stories highlighting individuals. Chinese media tended to focus more on collective impacts, such as the impact of the pandemic on students and education. “It’s interesting because these cultural differences kind of play into how journalists might write stories in the different countries,” Chen said.

At the same time, U.S. coverage shifted over time to recognize the complexity of COVID-19 and how it was a multifaceted risk. The U.S. media talked about the impact on small businesses, the ongoing impact on families and, when it was signed in March 2020, the CARES Act. Chinese media remained more or less focused on the same topics throughout the study duration, the authors found.

[Read more: Tips for reporting on vaccines, hesitancy and misinformation]

Overall, a big theme that emerged was also how the U.S. media tended to play the role of a watchdog, while Chinese media tended to be much more of a cheerleader. One possible explanation for this, according to the study:

Part of the difference in representation and focus on political coverage could be due to the different media systems. In the Chinese media system, limited press freedom and high levels of state intervention may have prevented coverage of political conflicts, while emphasizing how well the country was coping with the outbreak. In the United States, in contrast, high levels of press freedom combined with a competitive media market may have led the news media to cover politics more to cater to the high levels of political polarization among American audiences. Therefore, while it might be that there was more political conflict in the United States than in China during this time period that conflict and the coverage of such conflict might also reflect what each government and media system allow for. It could be that conflict in the United States was just more transparent, and media were able to then further broadcast that conflict.

What could all this mean for future risk and pandemic communication? “If the news continues talking about the leadership doing a bad job, then it might create very confusing signals to citizens,” Chen said. “This is where I would think about depoliticizing COVID-19 and instead talking about the hope of science to the public.”

Chen said the aim isn’t to glaze over political missteps or only put a positive spin on things, but instead to aim for a good balance between the hopeful stories and those that might dampen the outlook for a given crisis.

As far as future steps, Chen and her group are continuing to look at coverage past May 2020 to see how themes continued to evolve beyond the initial months of the pandemic. The group is also looking at how news narratives about collaboration (or lack thereof) between different countries during the pandemic may have affected how people perceive those from different racial and ethnic groups.

This article was originally published by Nieman Lab and is reproduced here with permission.

Photo by Mufid Majnun on Unsplash.