In Paris, some 150 world leaders have gathered for the United Nations’ annual Conference of Parties (COP) event. There, they will work to establish a legally binding international agreement aimed at stemming the tide of global climate change, the first of its kind since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.

Also present? Approximately 3,000 journalists covering the talks for news outlets around the world.

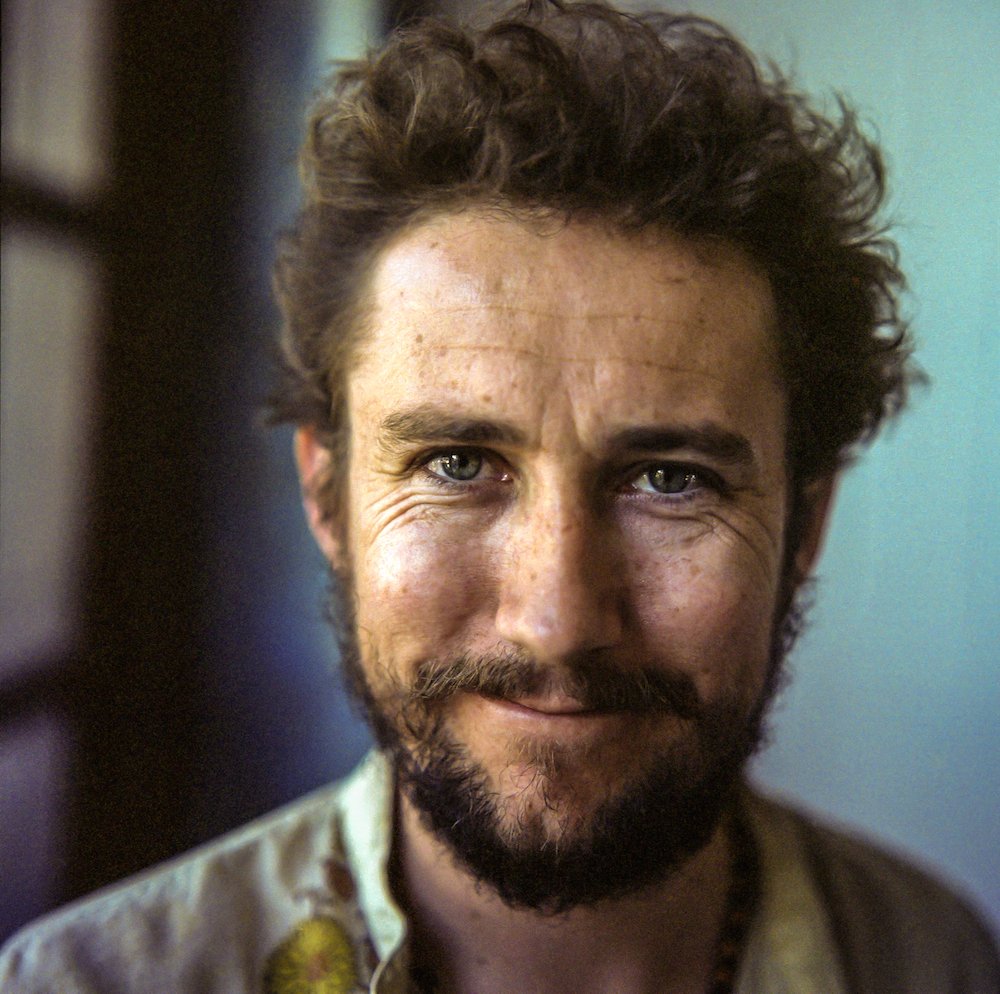

Climate Central reporter John Upton, one of the journalists currently covering the COP21 Climate Conference, said the immense scope of COP21’s media coverage indicates how far the issue of climate change has come over the last few years.

“I just think it’s incredible that 3,000 journalists are about to converge to cover an issue that five or 10 years ago was somewhat of a marginal one for a lot of people and for a lot of publications,” he said before the event. “I’m a fairly generalist environmental reporter, but climate change is such a hot issue right now — there are a lot of jobs for journalists to cover it."

Given the sheer size of the media presence at COP21, it’s clear that environmental journalism is more in-demand than ever. IJNet recently spoke with Upton, and he offered some tips for aspiring science and environmental reporters:

Don’t make researching harder than it has to be

Anyone can technically become a science reporter, Upton said. All it takes is the time and thought needed to investigate environmental issues, as one of the best ways to obtain scientific research — Google Scholar — is free to use.

“If you use Google Scholar, you’re going to pick up a lot of the main papers,” Upton explained. “And because there’s so much consolidation of these things, you can go to places like nature.org, find the highest-profile journals that publish research on the topic you’re addressing and just search in each of those individual journals.”

Upton said it’s possible for journalists to navigate around journal pay walls, something many reporters don’t realize. Doing so is surprisingly easier than one might assume — all it takes is asking nicely.

“Once you find the studies that interest you, if you don’t have a subscription, you may only be able to retrieve the abstract plus some other information, including details of the scientists who produced the study,” he said. “But those scientists are always happy to share the study with a journalist. You just have to email them, and they'll generally respond pretty quickly.”

Stay skeptical

Upton also stressed the need for science reporters to remain skeptical of every journal they read and every scientist they speak to for a story. While the scientific community generally follows the principle of peer review when publishing scholarly work, the peer review process isn’t immune to inherent bias.

“I think a lot of journalists think that the vetting they would normally need to do for a story is already taken care of by the peer review process at a journal, but that’s just not the case,” he said. “It’s very easy for misinformation and false assumptions to slip through this process, and there’s always a risk of journalists regurgitating the errors or incorrect assumptions of a team of scientists.”

Think locally — and globally

Climate change is a global crisis, but many audiences will have difficulty grasping its importance if they don’t see the effects of climate change in their local communities, Upton explained. It’s thus important for science journalists to scale down their climate change coverage and focus on these local stories.

“If you want someone to pay attention to your reporting, you need to speak to the issues that address them, and that means local reporting,” he said. “So if you’re reporting that the globe has warmed up .78 degrees Celsius, or sea levels have risen eight inches or something since 1880, it’s all very distant and it’s all very vague. When you’re reporting on climate change, it is helpful for your audience if you can hone in on the local impact and local opportunities to reduce pollution and so forth.”

The same goes for covering multinational environmental issues, such as the transatlantic wood pellet industry Upton investigated for his recent “Pulp Fiction” piece. While burning wood pellets for energy does have a global impact, Upton made a point to include stories from wood pellet manufacturing communities throughout the American Southeast as well.

“I would say the most important thing internationally is to make sure you’re paying as much attention to any foreign aspects of your reporting as you are to the domestic ones,” he said. “I had to do a lot of leg work and a lot of reading when it came to understanding the laws and policies in two different countries; it can be difficult, but it can also be very rewarding, and it’s really important.”

Click here to read more of Upton’s tips for investigative science journalists.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via jean-pierre chambard.

Photo of John Upton taken by Rajan Zaveri.