For more than 15 years, Global Voices has worked with local journalists, translators, activists, researchers and civil society actors around the world to promote understanding across borders. The newsroom produces stories that incorporate important regional context, enabling readers to acquire greater understanding of different societies and cultures.

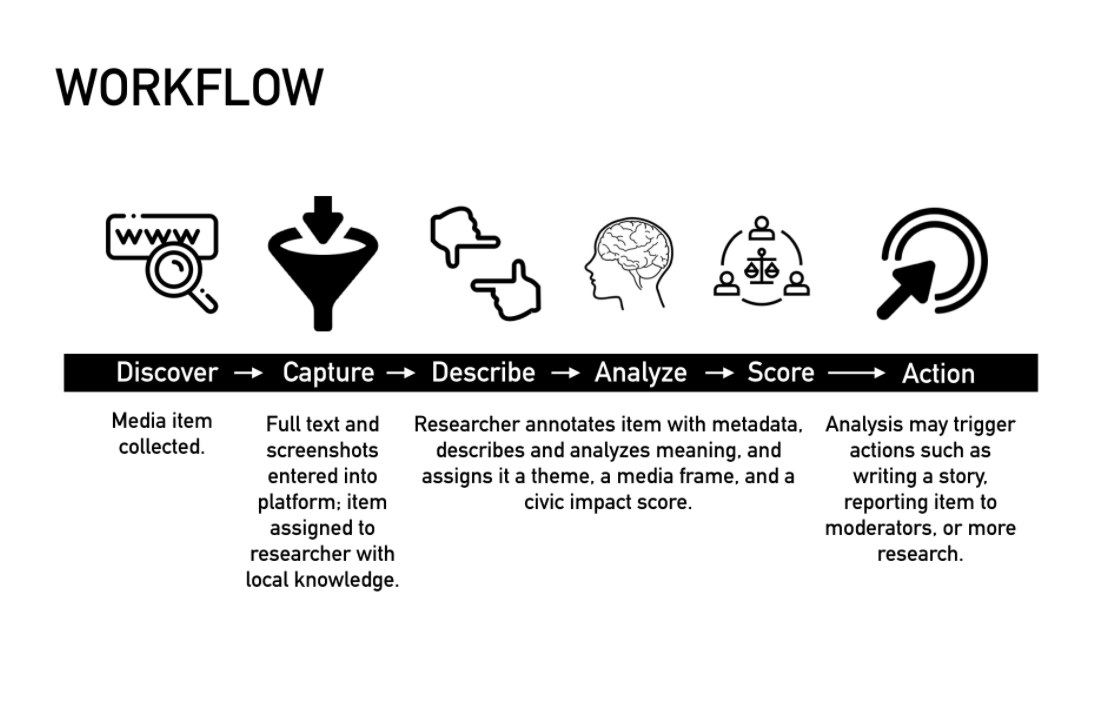

In recent years it became clear to the newsroom that mis- and disinformation, disruption and confusion among audiences was increasing, especially on social media. To address the growing concern, Global Voices launched a method in 2019 called the Civic Media Observatory to investigate and decode how individuals in diverse, “seemingly chaotic media ecosystems” interpret content, and in turn construct their reality.

"It grew out of a sense that too many projects focused on mis/disinformation are primarily reacting to bad information rather than trying to identify how that information actually informs or misinforms readers," said Global Voices Executive Director Ivan Sigal, adding that the Observatory explores cultural phenomena that might make information more difficult to understand.

The investigations

Since the project’s launch, Global Voices has used the Observatory’s methodology in more than 10 investigations — each using its own database — into topics ranging from COVID-19 to local elections in countries like Myanmar and Bolivia. Today, there are 12 researchers involved in two Observatory projects — one about the China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and another focused on political coverage in Myanmar.

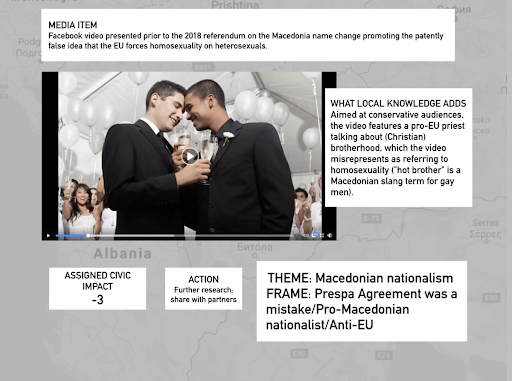

The local researchers add media items, such as stories and memes, to a database, which is hosted on Airtable. They then analyze the content pieces and explain their context, addressing themes, subtextual information and missing details, among other criteria. The analysis enables the newsroom to register patterns, which they refer to as themes or narrative frames. The Taiwan Elections Observatory is one example, now made public, of how this work was carried out.

"All information is encoded in cultural forms, and those forms are expressed as narrative frames,” said Sigal. “If we can identify and define those frames, then we can articulate underlying assumptions, preferences, ideologies [and] opinions that people bring with them when they write, speak and read."

The Observatory essentially goes one step further than more traditional fact-checking efforts, according to Sigal. "Fact-checking projects look at the factuality of individual media items, but are they also able to explain how people interpret those items on the basis of underlying narratives?” he said. “Social media companies with content moderation removal policies also have for the past few years focused on individual items, rather than their interpretation."

[Read more: Journalism nonprofit Orb Media addresses global sustainability]

For instance, when investigating discussions on social media about COVID-19 vaccines in Africa, researchers detected debates around the pros and cons of vaccines developed in China. They registered several frames through which to analyze the main arguments being made, ultimately writing two stories about how African countries were sourcing and debating the use of these vaccines.

The Observatory’s research has helped discover how WhatsApp became an effective tool to organize feminist groups during the pandemic in Venezuela, and how in Bolivia, the Aymara people turned to Facebook to call attention to their disagreement with the country's independence celebrations. The team has also investigated the impacts of how an Islamophobic post led to deadly violence in Bangalore, and the ways in which Indigenous peoples in Latin America are resisting the pandemic and accessing better care.

The teamwork

It has been important to create camaraderie among the researchers, especially as they’re spread out around the world, said Alexandra Esenler, the Observatory’s project and development manager. Esenler said she encourages regular communication within the team, and she makes time for calls during which team members can talk freely. She also ensures that instructions and trainings are clear for those who are not native English speakers. "By building those relationships, I think everyone feels more invested and excited about the research,” she said, adding that the database’s impact helps develop a sense of teamwork, too.

Building a support system for the researchers is also critical, said Melissa Vida, Global Voices' Latin America editor. "While working on the [Observatory], I realized that a lot of the themes and frames researched online can be hugely triggering for our team,” she said. “For example, it must be difficult for an Indigenous person in Bolivia to non-stop look for extremely violent and anti-Indigenous and racist content online. It becomes even more important as social media's algorithm will remind you of this content regularly after doing the research."

[Read more: Fact-checkers team up with social media influencers to combat misinformation in Nigeria]

Collaborating with Big Tech

Last year, Global Voices partnered with Facebook to support the Observatory. “We think that this research could be a good way to engage with the concerns many social media platforms have about the impact of their work on civics," said Sigal. He and Vida both agree that social media platforms need to do more than just remove posts that violate their policies.

“We are aiming to present analyses that can help the social media companies understand how narratives work. It's one thing to understand that information and its effects [are] not static in media ecosystems, it's another to apply systematic thinking to understand how to act in response.”

Through the Observatory, Global Voices plans to keep producing stories for their newsroom, while also sharing its methodology with other organizations. Said Vida: "In our polarized, algorithmic digital age, I believe the [Observatory] method has to be taught to every journalist so they can see the different narratives at play in online — and offline — communities.

Giovana Fleck is a multimedia journalist and researcher who specializes in data and politics.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Artem Beliaikin.