The increasing violence against journalists around the world is worrisome. So far 33 journalists have been killed this year, for reasons directly connected to their job, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports.

Impunity has been the rule after most of these murders: CPJ says that 90 percent of the 370 killings of journalists in the past ten years did not result in a conviction. While international and non-governmental organizations consider new approaches to combat this problem, the role of the media in this process is rarely discussed.

It may be, though, that journalists have a role to play in protecting their own. By covering violations of press freedom and cases of violence against journalists, the media can raise awareness and perhaps make conditions safer by pressuring governments to act.

As part of its advocacy work on press freedom and safety, the Open Society Foundation’s Program on Independent Journalism commissioned research by a group of four students at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) to analyze press coverage of journalists safety in five different regions.

The study was conducted by me, Carolina Morais Araujo (Brazil), Xin Yi Cheow (Singapore), Angela LaSalle (U.S.) and Natalie Felsen (U.S.), under the supervision of Professor Anya Schiffrin as part of her course, Global Media: Innovation and Economic Development. We analyzed press coverage of recent killings of journalists in Brazil and Nigeria as well as cases of intimidation and harassment of journalists in Hong Kong, Malaysia and South Africa.

Research phase one

Our research was divided in two phases. First, we analyzed the content of major outlets from the countries chosen. In the first phase of the project, we coded print and online newspapers: 228 articles from three Brazilian newspapers; 75 articles from five Malaysian press outlets; 50 pieces from two Hong Kong’s newspapers; 27 articles from two newspapers in South Africa, and 51 articles from 17 media outlets in Nigeria.

Because Columbia University had limited access to international print newspapers, we found the articles through web, archive searches of each paper and Columbia University’s online databases. Reprints of articles were not coded; we only included original reporting.

The articles were subsequently coded using quantitative categories; such as word count, mentions on the front page and number of sources; and qualitative tags, including type of sources, frequent words and type of article. We used Excel to keep track of our coding and record the content analysis.

To visualize patterns, we chose Infogr.am to create graphics, which we found user-friendly. It lets users choose from pre-made templates and 16 types of charts, or create their own styles. The charts helped us to find tendencies in the coverage we were analyzing. We concluded that, overall, coverage has not followed best reporting practices. Common shortcomings we found include low number of sources, lack of investigative effort and little expertise of reporters who covered recent cases of press freedom violations. Below are some Infogr.am graphics of our analysis.

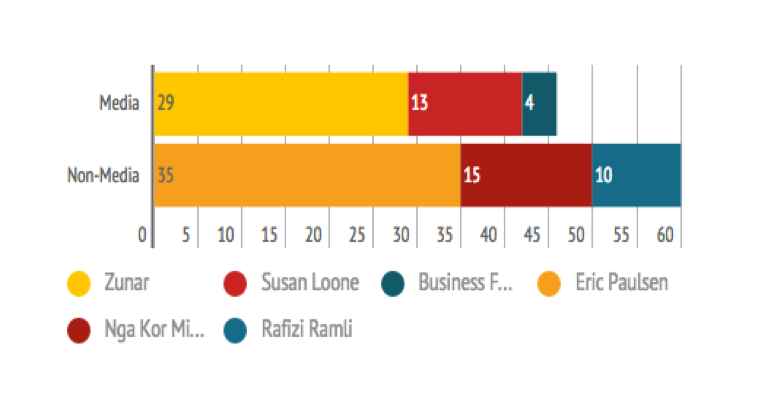

Comparison between the coverage of the arrest of journalists (media) and other professionals (like lawyers and politicians) due to the Sedition Act in Malaysia

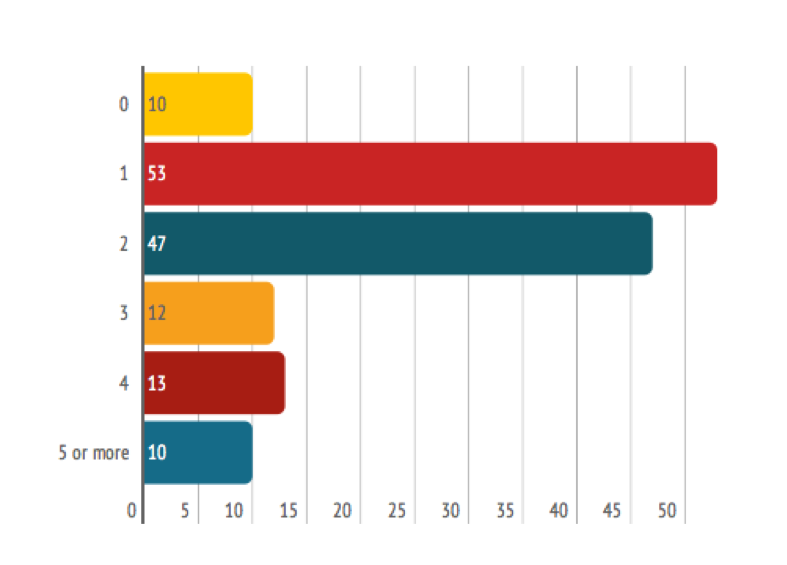

Number of sources used in the articles about the killing of a video reporter in Brazil in 2014 in the three nationwide newspapers

Research phase two

More than just visualizing the data, we realized it would be essential to understand the meaning behind the charts. So in the second phase we interviewed reporters, editors and other media professionals about the coverage and their opinion on best practices in reporting on violence against journalists. Some of the interviewees were journalists who covered the cases we studied, while others are familiar with the local media landscape.

In total, we interviewed 14 media professionals: five from Brazil, three from Malaysia, two from Hong Kong and four from Nigeria. The interviews were conducted through face-to-face meetings, Skype, phone, email and instant messaging. Questions varied by case, however most focused on what made a story about a threatened journalist more newsworthy and suggestions on how to improve the status of media freedom and the safety of journalists’ working environments.

Talking to people “on the ground” helped us deepen our knowledge of the context of coverage and the particularities of local media in the countries we researched. Listening to different perspectives let us review assumptions and understand the multiple variables that influence the extension of coverage and the responses of different stakeholders.

Finally, the interviews showed us that, given the different conditions of safety and reporting practices in each country, we should be very cautious about analyzing tendencies across countries.

After analyzing hundreds of stories, we found that overall there was little reporting on recent incidents of harassment and killings of journalists. In Malaysia, for example, we found that media outlets gave more space to the cases of lawyers and politicians than to journalists who were arrested under Malaysia’s Sedition Act.

There were exceptions, though. In Brazil, the 2014 killing of video reporter Santiago Andrade while he was filming a street rally in Rio de Janeiro triggered a national discussion in the media about journalism safety. In Nigeria, the case that received the most coverage was the death of Enenche Akogwu, a cameraman killed in 2012 in the line of duty while reporting on one of the larger Boko Haram attacks.

We concluded that there was more coverage when there were images of the killings available and when the journalist was covering a major event or worked for a well-known outlet.

Even in the most publicized episodes, the national media often failed in tracking the police investigation and the judicial proceedings after killings and episodes of intimidation, which contributes to tendencies of impunity and journalists’ vulnerability. By reporting threats and violence against themselves and their peers, journalists and media outlets can play a more active role on improving their own safety and work conditions.

Carolina Morais Araujo, 30, is a Brazilian journalist and a Master of International Affairs candidate at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) of Columbia University.

Image CC-licensed on Flickr via yanrf