As COVID-19 swept the globe, data journalism played a critical role in providing reliable information about the rapid onset and ferocity of the pandemic.

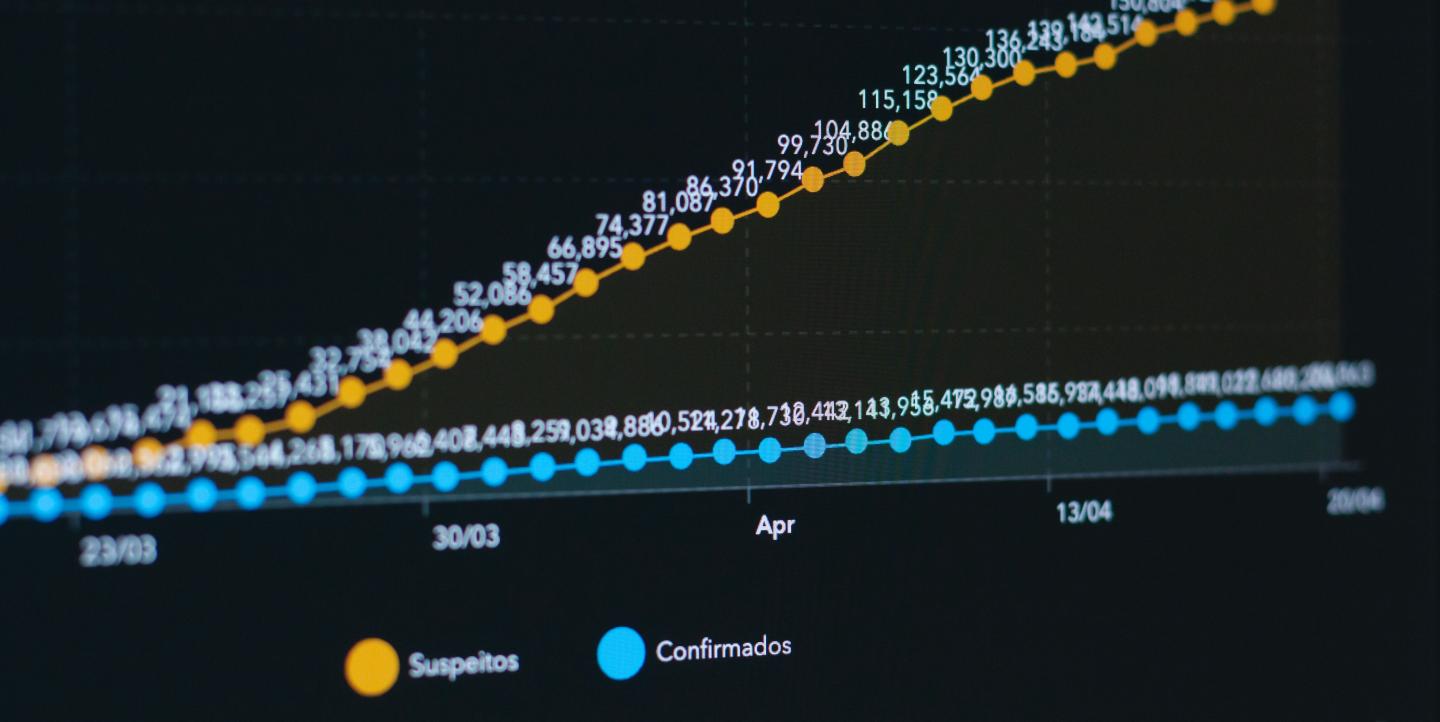

Interactive maps traced the virus through cities and neighborhoods. Graphics illustrated how the virus invades and ravages the body. Fever charts marked cases and deaths. It was public service journalism at its best.

But, what did data show about how the virus impacts marginalized communities?

“Giving voice to the voiceless is more critical now than ever,” said two-time Pulitzer Prize-winner Martha Mendoza of the Associated Press. “Marginalized immigrants, the homeless, the incarcerated [and] the poor need to be reached as part of the coronavirus coverage.”

In May, a New York Times story warned that the virus was worsening social and financial inequality, while also having a larger impact on marginalized communities. The following examples show how data has helped tell the story of the effect on vulnerable populations:

Breathing life into numbers

A team of ProPublica reporters wanted to learn about the people behind the numbers, and see what that meant for the city's minority communities, so they started an investigation into the data. After obtaining the names of Chicago’s first 100 COVID-related fatalities from county officials, ProPublica reporters turned to Nexis searches, social media, obituaries, funeral homes, family and friends to build their database.

Operating out of five cities across the country, they held meetings via Zoom and used Google Docs to coordinate reporting, ultimately publishing the feature, “COVID-19 Took Black Lives First. It Didn’t Have To.” The project’s major findings included:

- An analysis of medical examiner data showed that 70 of the first 100 recorded victims were Black. Many of the first 100 lived in segregated neighborhoods where the median income for 40% or more of the residents is less than US$25,000 a year

- Most of the first 100 victims were already sick with multiple health conditions

- Some neighborhoods lacked well-resourced hospitals or healthcare

- Poverty and lack of access to medical care were among factors that contributed to the higher death rates

In phase two of the investigation, reporters searched for those who knew the deceased.

“With COVID-19, we hear so much about numbers and statistics and comorbidities. We have to remind ourselves, there is a human being behind every single number. For us, it was important to make sure we were incorporating that humanity into our reporting,” said Duaa Eldeib, a member of the ProPublica team.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 23% of reported COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. were African Americans as of May 2020, even though Black people make up roughly 13% of the U.S. population.

Interactivity sheds light on COVID

The flood of information on COVID-19 has been dizzying. Niko Kommenda, visual projects editor for The Guardian, turns to interactive journalism to help make sense of it.

“Good data journalism is key to understanding how the virus and lockdown measures have affected our lives more widely, what new inequities they have revealed and what lessons we can learn for the future,” said Kommenda.

With interactive tools, readers can find their areas or demographic groups in large datasets and localize the impact of the disease. These tools can also help provide perspective and context to complex data.

For instance, the Guardian’s data project team found that Londoners living in poverty-stricken areas have less access to private green spaces and would be hardest hit by public park closures. Collaboration among project teams and visuals revealed that ethnic minorities in the UK have a much higher risk of dying from COVID-19, raising further questions about disparities in access to healthcare and safe working conditions.

Kommenda’s advice to data and visual journalists covering the virus: “Identify stories where you can give added context and amplify otherwise unheard voices,” said Kommenda. “That’s why we at The Guardian focus on covering, among other things, the social inequality aspect and the environmental implications of this crisis.”

COVID is everyone’s beat

Everyone, from sports editors to fashion writers, have become part of the team covering COVID-19. “[It’s a golden moment for data journalism,” said Steve Doig, data specialist and journalism professor at Arizona State University. “Every beat reporter can make a contribution.”

If you’re a beat reporter working the pandemic into your reporting, Doig offers a list of tips:

- Take your expertise and look for COVID impact. What kind of stories can be spun off your regular beat?

- Check effects on voiceless and marginalized communities. How are they impacted?

- Familiarize yourself with data sources such as the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, and data repositories from The New York Times and The Washington Post.

- Look for someone who does census journalism, and start asking questions. In which part of town are the most people getting evicted? Where are the most cases? Census Reporter is a helpful source to dig into the data.

As part of her International Center for Journalists Knight Fellowship, Fabiola Torres created Salud Con Lupa (Health with a Magnifying Glass), a digital platform for data-driven coverage of the pandemic. When planning COVID coverage, she advises reporters to start with a series of questions such as:

- What is the most important thing I need to explain to my audience about the pandemic?

- What is at stake with this disease?

- Who is benefitting from this global crisis?

- What are the social and economic side effects?

- Is the virus creating even more poverty and inequality than existed before?

“I always tell reporters we also have to offer hope with our stories. We must show the problems of the virus, but also that it’s not the end of the world. The public gets anxious and begins to despair when they only see bad news every day,” said Torres. “We have to find a balance and look for solutions.”

This article was adapted from a story originally posted on DataJournalism.com. It was edited and republished on IJNet with permission.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via KOBU Agency.

Sherry Ricchiardi Ph.D. is the co-author of ICFJ's Disaster and Crisis Coverage guide and international media trainer who has worked with journalists around the world on conflict reporting, trauma and safety issues.