Assassinating journalists can be costly. It can attract too much attention.

Getting creative with the law to make journalists disappear and grind their reporting to a halt: less so.

Today, more and more, autocrats like Guatemala's Alejandro Giammattei leverage legal measures to suppress independent media. It provides themselves a semblance of cover that other hardline measures might not otherwise offer.

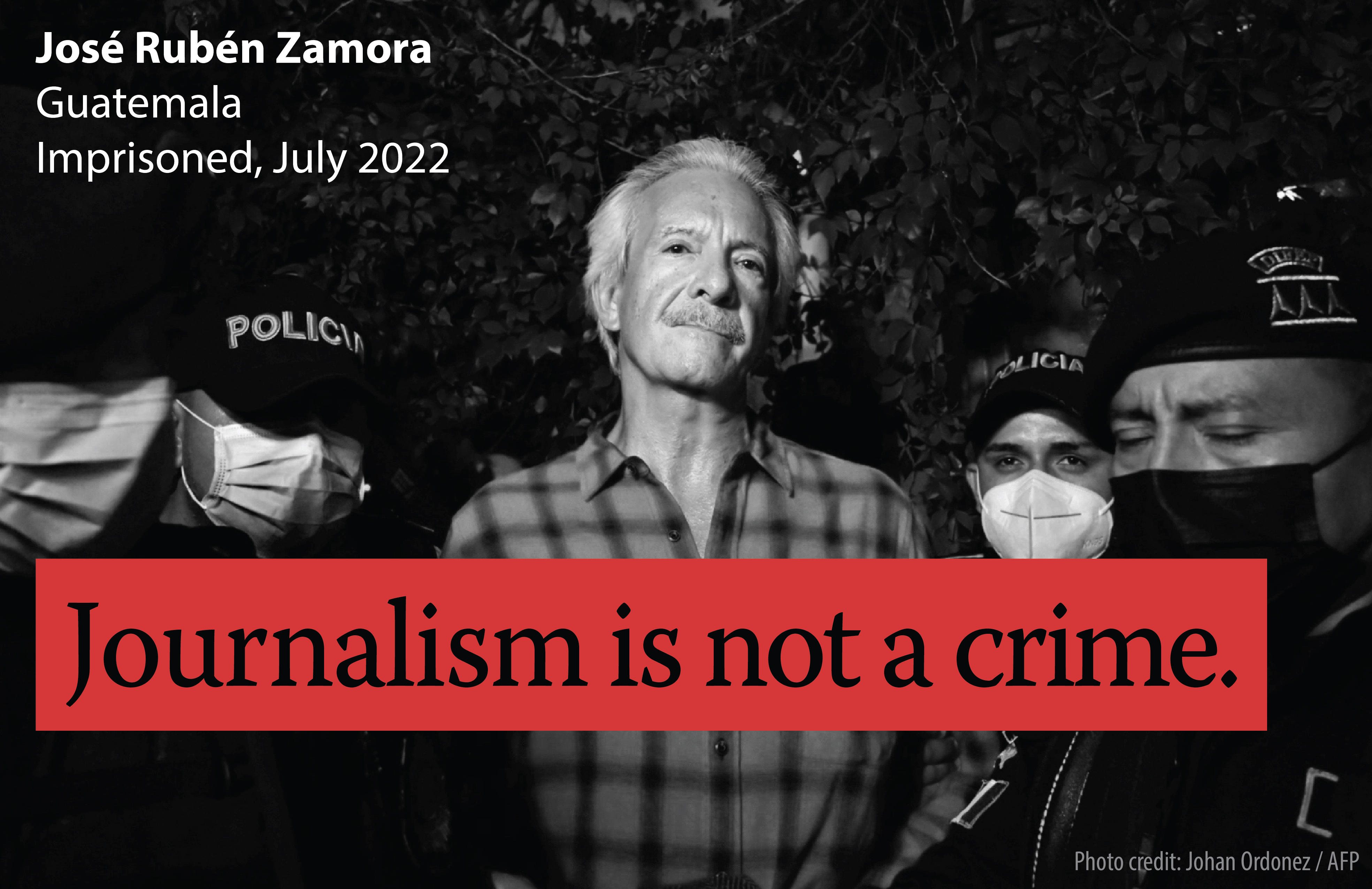

For the past year, the case of Jose Rubén Zamora in Guatemala has been emblematic of this type of crackdown on journalists and newsrooms that has taken root globally. Arrested in July 2022 on bogus charges, Zamora has spent the past year behind bars in an effort by Guatemalan authorities to stifle his reporting.

“The government – the Alejandro Giammattei administration – has held him hostage for 365 days this upcoming Saturday,” said Zamora’s son, José Zamora, at a press conference held Wednesday by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) to mark the anniversary of the arrest.

After months in pre-trial detention, and trial proceedings during which his lawyers were persecuted themselves, Jose Rubén Zamora was convicted and sentenced to six years in prison last month on charges of money laundering. His outlet, elPeriódico, was forced to shut down in May due to financial and legal pressures exerted by the government.

“They have him unjustly imprisoned on spurious charges, and they made him go through and face this process that is an absolute violation of due process, and it needs to end,” said his son, who is the chief communications and impact officer for Exile Content Studio.

Joining him on the panel Wednesday were exiled Guatemalan journalist Bertha Michelle Mendoza and Carlos Martínez de la Serna, a CPJ program director. Sara Fischer, a senior media reporter at Axios, moderated the discussion.

Guatemala is the only democracy in Latin America with a journalist in prison, Zamora noted. Under the Giammattei administration, more than 750 attacks on journalists have been recorded. At least 20 Guatemalan journalists have fled the country.

“[Giammattei] has power over all institutions,” warned Mendoza. “He has the courts – the Supreme Court, Constitutional Court, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, Attorney General’s office – which he is using to unjustly persecute and imprison not just journalists, but also judicial operators, activists, human rights defenders, even political scientists, who say things that run against the narrative he wants to impose.”

Due to her reporting, Mendoza had become a frequent target over the years of harassment, both online and in person. She went into exile in the U.S. after investigating Giammattei over allegedly taking bribes from state contractors, resulting in pieces published by CNN en Español and El Faro in February 2022. She fled, she explained, after Jose Rubén Zamora alerted her that the attorney general seemed intent to detain her.

“The country is currently going through a historic crisis, thanks to the dictatorship of Alejandro Giammettei, who has forced dozens of journalists, justice operators and human rights defenders to flee,” she said. “Others remain in the country under terrible threat of being persecuted for telling just the truth.”

A firmer, more consistent response by the international community to the Giammattei government’s crackdown on journalists is imperative, the panelists urged.

The Trump administration, in particular, emboldened anti-press efforts and undermined the media around the world, said Martínez de la Serna: “We need to ask ourselves if we would have seen this happening if governments [...] were consistent in the defense of press freedom worldwide.”

The response last year to the elder Zamora’s arrest was too slow, he further cautioned. It must be made clear that the current situation is unacceptable.

“The whole press freedom situation in Central America is at stake,” said Martínez de la Serna. “In Guatemala, in Honduras, in El Salvador. Even in Costa Rica, there’s some concerning signs of this, though the situation is different. Demanding the release – the justice due in the case of Rubén Zamora – is an essential message for the future of the region.”

Zamora echoed these concerns, what he called a “domino effect.”

“We’ve been seeing it worldwide, from Russia to the Philippines to Venezuela, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Mexico and Guatemala,” he said.

Looming elections next month offer some cause for optimism, though they remain shrouded in uncertainty. In a surprise result, anti-corruption candidate Bernardo Arévalo of the Semilla Party advanced to a run-off on August 20, against the right-wing former first lady, Sandra Torres, of the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE) party. Efforts to reject the results of the first round of the election have been condemned by independent watchdogs, and spurred protests across the country.

“There is a glimmer of hope today, with respect to [Semilla], and there is also an awakening among the Guatemalan people precisely because this small group of corrupt officials made [Semilla’s] candidate more visible,” said Mendoza. “This candidate, Bernardo Arévalo, has an anti-corruption platform, and if this platform wins there will definitely be change.”

In the meantime journalists must continue their coverage, Zamora stressed: “Make sure these stories don’t stop, and that these repressive regimes know that the world is watching.”

José Zamora is a member of ICFJ’s board of directors.

Photo by Shalom de León on Unsplash.