When editors at Dawn decided to take an in-depth look at the proliferation of suicide in Pakistan, they quickly hit a roadblock. They couldn’t find any official records since the topic is taboo, and rarely discussed publicly.

(Trigger warning: This article focuses on suicide, which can be triggering for some readers. Please proceed with caution.)

Their goal was to raise awareness of “Pakistan’s Silent Suicide Problem” by producing a high-profile multimedia project. However, they first had to find a way past religious and cultural barriers in the country.

Dawn editor Jahanzaib Haque explained that mental health is poorly understood in Pakistan, and suicide is particularly ignored and covered up. “It is this taboo, clubbed with the lack of reporting, and the lack of available stats and local research, that prompted us to explore the issue in-depth,” he wrote in an email.

Since they couldn’t find any data on the topic, the team decided to collect their own. In December 2018, they posted an online survey asking respondents to share their thoughts, opinions and personal accounts regarding suicide.

For guidance, Dawn’s editors turned to existing suicide-related surveys from reputable organizations across the globe. They noted trends in the types of questions asked, and the language used to build their template. Before it was posted, it was reviewed by a noted Pakistani psychiatrist and researcher on the topic.

“This had never been done before,” said project co-director, Atika Rehman. “We didn’t know what to expect.”

The results surpassed expectations. They received 5,157 responses, and more than 2,000 included intimate details of respondents’ own struggles with suicide, or their firsthand experiences with family and friends.

Reporters combed through the data on why Pakistanis are taking their own lives, organizing it into thematic categories that include sexual abuse, addiction, financial pressure, eating disorders, sexual identity, domestic abuse and bullying, among others.

Investigators were shining a light on what long had been a stigmatized topic. The questionnaire gave voice to people struggling in all corners of Pakistani society, from university students and professionals to people living in poverty and women trapped by social mores.

“Personally, I was shattered by some accounts, and I feel they will stay with me forever,” said Rehman. “The emotional toll was beyond what I imagined . . . I felt empowered [by the number of responses] and helpless at the same time.”

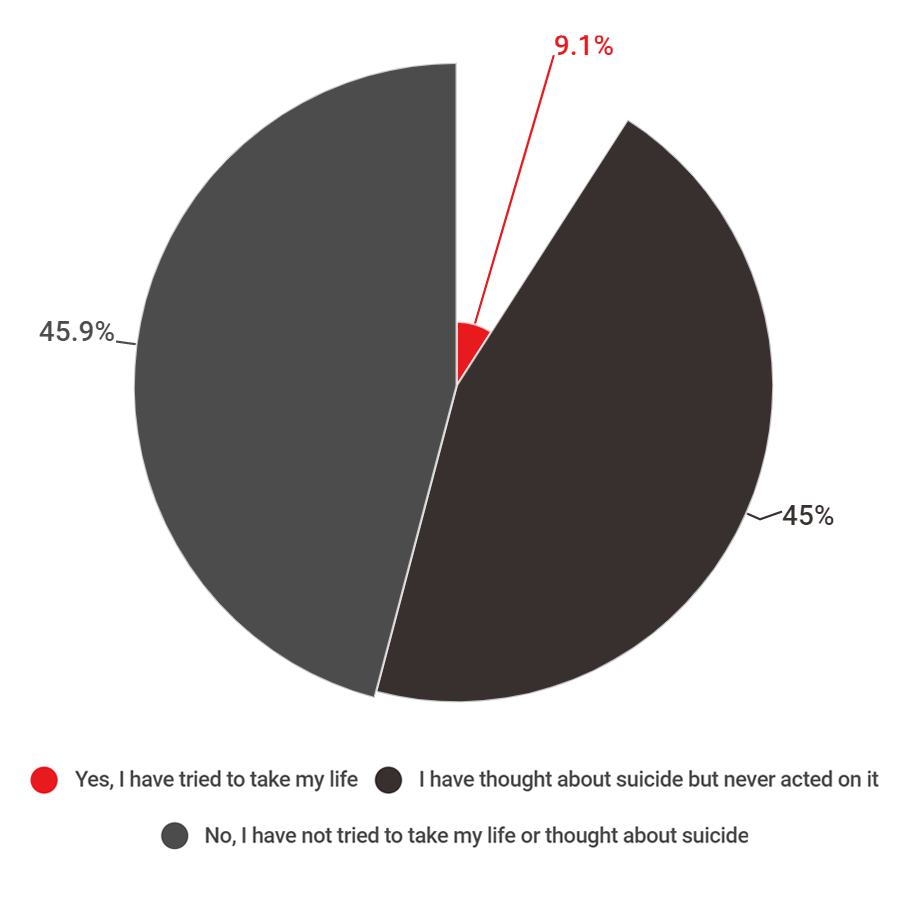

Researchers discovered that nearly 40% of respondents knew someone who took their own life, and 45% of respondents have had suicidal thoughts in the past.

For insight into the personal responses, Dawn’s project team turned to Murad Moosa Khan, professor of psychiatry at Aga Khan University and president of the International Association for Suicide Prevention.

“The stories in the posts were extremely powerful and tell us what people in the highly complex and convoluted society of Pakistan are going through,” Khan wrote. He described an “underlying deep sense of isolation and shame, of suffering in silence [and] a fear of seeking help due to stigma or being judged.”

Since the topic was so sensitive, editors faced difficult decisions on what to publish. They used two criteria for selecting respondents testimonies: clarity of the writing and category the testimony fell under — relationships, societal pressure, sexual identity, domestic abuse or others.

During the vetting process, “We relied on our editorial judgment and the [psychiatrist] to guide us in terms of what was sensational or triggering versus importance in being a clear example within a certain category,” said Haque, project co-director and chief digital strategist of Dawn. “For example, we removed any graphic details related to acts of violence or abuse, self-inflicted or otherwise.”

Dawn’s project team spent hours sifting through the data, and they soon realized the impact it was having on their own emotional wellbeing.

“We didn’t anticipate how emotionally taxing it would be for us personally. If I could do the project over again, I would certainly form a support group to talk about the emotional impact of these stories,” said Rehman. “I would suggest that the editors reading the testimonials seek professional help if they were feeling distressed.”

She offered four guidelines for those considering a similar project:

-

Involve a mental health professional and get their advice on how to proceed with maximum sensitivity

-

Don’t frame the story as sensational

-

Provide lists of doctors/mental health professionals, and other resources that readers in distress can turn to

-

Include trigger warnings, brief statements that reading the content may provoke an adverse reaction. A warning might read, “The following accounts, which include details of suicide and suicide attempts, may upset some readers. Please proceed with caution.”

The editors were pleased with the strong public response. “Readers said it was an eye-opening piece that made one confront how widespread [suicide] is in Pakistan,” said Rehman, who recently became Dawn’s London correspondent.

The project received 102,000 page views after the initial launch. Since then, between 45-100 people have tapped into it on a daily basis, and more than 4,000 have shared it on Facebook.

“We were particularly happy with Twitter feedback from [mental health] experts, politicians, members of the media and celebrities who also commented on and shared the project, terming it a valuable and important read,” said Haque.

Main image is a screenshot of Dawn's project, "Pakistan's silent suicide problem."