Misinformation is more common than ever in Indonesia today as its spread has become increasingly diversified and difficult to suppress.

In April alone, when the country held its general election, Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology identified 486 pieces of misinformation shared across several online platforms — 209 of them politically-related. The Ministry noted that this number surged leading up to the April 17 election, and has only continued to increase after.

To better understand how information — both credible, misleading and false — spreads, and why, I conducted a survey in February 2019 with Tirto.id, one of the newsroom partners I worked with in Indonesia as an ICFJ TruthBuzz Fellow. What I found challenges the assumption that a lack of critical thinking is the prime motivator that leads people to reshare misinformation so easily.

Survey design

More than 1,500 people from the country’s most populous island of Java took the survey, answering 31 questions about how they access information on a daily basis. We also included three sets of images, including articles from mainstream media, viral memes and screen captures of social media posts. We asked respondents to decide whether the information in the images was accurate or not, and if they wanted to share the images online.

The first set of included non-political social media posts about vaccines and health, and Rohingya and Gaza Strip refugees, all of which were either unverified posts from non-credible sources, or misinformation. The images in the second set were political in nature, taken from credible media outlets as well as partisan Facebook groups. These were all related to then-presidential candidates, Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto. The third set included images of accurate, fact-checked articles, published by the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology and fact-checking outlets.

Who’s sharing, and what are they sharing

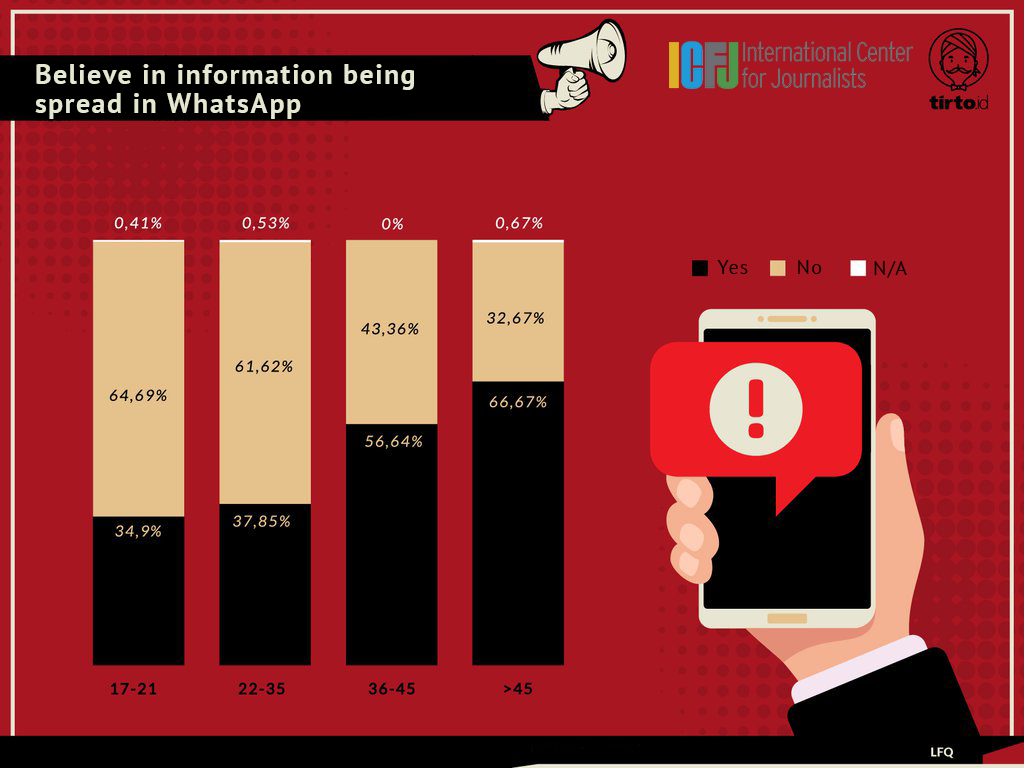

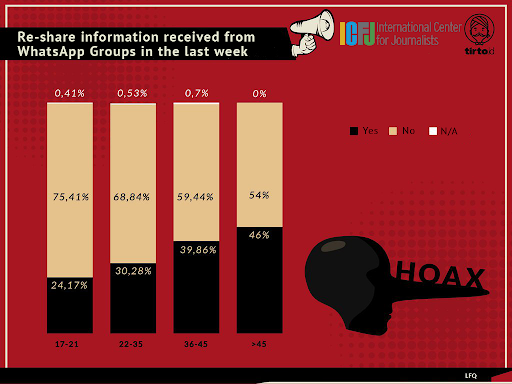

We tested a number of factors that might affect the likelihood that a respondent would share information on WhatsApp, including gender, educational background and age. While gender and education had no effect, our survey results showed a direct relationship between older age and higher trust in the information circulating in the messaging app.

While 41% of all respondents said they trust the information they receive in WhatsApp, this number jumps to 67% for respondents older than 45. Just 35% of respondents ages 17-21 said they trust the information they come across in the messaging app.

Older people are also more likely to share the content they encounter from one group to another in WhatsApp. Nearly 50% of adults older than 45 said they shared information they received in one WhatsApp group with another, compared with 24% of 17 to 21 year olds and 30% of respondents between the ages of 22 and 35.

Respondents were most likely to share images containing unverified claims or misinformation. An image of vaccine conspiracy content proved most shareable at 31%, followed by an unverified image of Indonesian runner Lalu Muhammad Zohri celebrating a victory with the Polish flag (20%). At least 10% of respondents said they would share each image containing false or unverified information.

In all, respondents were most likely to share health-related content, false or not, followed by messages containing information about nationalism, the economy, religion and politics — all sensitive issues for Indonesians.

Why misinformation spreads

Understanding who shares misinformation, and what they’re sharing, however, doesn’t explain why they’re doing so.

To better understand the “why,” we asked Ismail Fahmi, the founder of the social media analytics system, Drone Emprit. He explained that there are two main types of misinformation spreaders. First, there are people who believe that any information circulating in messaging platforms is true, and therefore share it. Then, there are those who don’t care about the accuracy of the content, so long as they receive the information from someone they trust.

A lot of work around misinformation today is based on the assumption that those sharing the information are unable to separate fact from fiction. This forms the basis of media literacy initiatives that teach critical thinking skills to news consumers so that they are better able to identify unverified, misleading or false information.

We wanted to find out if that assumption is true, so we conducted a Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), which was developed by psychologist and professor Shane Frederick in 2005 to assess individual differences in critical thinking, alongside the pre-election survey. Those who pass the test are considered better critical thinkers than those who don’t.

When we administered the test during the pre-election survey, just 16 respondents — one percent — passed. Still, these more critical thinkers were not immune to sharing unverified or untrue information. Four of the 16 who passed the test shared anti-vaccine misinformation, and seven shared political misinformation.

We concluded that people who share misinformation do not necessarily consume information less critically, belying an assumption that the only key to fighting mis- and disinformation is teaching and training to develop these skills. While people who passed the CRT did spread misinformation at a significantly lower rate compared with those who didn’t, there are yet other reasons why people with strong critical thinking skills still pass on information that is unverified or untrue.

One of these reasons deals with political beliefs. When we examined comments on pieces of misinformation that had been debunked by Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, many of the people sharing information and posting comments were strong supporters of one of the country’s two presidential candidates last spring. From this, we determined that fervent political supporters were one group that tends to spread false or unverified information indiscriminately.

Older people, meanwhile, spread misinformation because they genuinely believe it to be true. Even others share unverified or false information because they trust the person who sends it to them.

To fight the spread of misinformation in the country, we need a better understanding of the reasons people share false or unverified claims on WhatsApp.

The research I conducted alongside Tirto was among the very first in Indonesia that attempted to better understand this phenomenon — and it should be just the start. Only with more knowledge of the issue can we start to develop solutions that address the various factors that motivate people to consume and share mis- and disinformation.

The first image shows Astudestra Ajengrastri working alongside partners at Tirto.id.

Content in this article was originally published on Tirto’s Instagram.