A giant cargo plane sitting on the runway is an unusual sight in Serbia’s international airport.

Two reporters from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) took notice of such a plane in June 2015. What was the plane transporting and where was it going?

OCCRP reporter Miranda Patrucić also suspected something strange after conducting a series of journalism trainings in the Middle East. A few times, people asked if she could help them purchase weapons from the Balkans. “I was just like, why are you asking me these questions?” she said.

These incidents helped fuel a yearlong investigation into whether weapons exported from Eastern Europe are fueling conflicts in the the Middle East.

OCCRP, a network of investigative reporters based in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, partnered with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) to produce "Making a Killing." The investigation found that Eastern European governments continued to approve mass weapons exports to countries like Saudi Arabia, despite evidence that many of these weapons may end up in war-torn countries like Syria. Even though government leaders insist otherwise, experts told BIRN and the OCCRP that this trade most likely violates international law.

Patrucić was among those who helped coordinate the investigation, which covered eight countries in Eastern Europe and involved thousands of pages of documents, hundreds of sources and more than a dozen reporters. She shared some of her thoughts with IJNet on how other newsrooms can tackle what’s arguably one of the most difficult subjects for investigative reporters: the illegal arms trade.

Getting focused

At the investigation's start, reporters and editors weren’t sure what they were going to find, or even how many countries they would focus on.

“Early on, we’d been following many leads, trying to figure out what’s going on,” Patrucić said. “Our scope was big because we didn’t know what we would be able to prove.”

When dealing with such a large, complex topic, Patrucić recommended spending time on pre-reporting and research — reading reports from international organizations and think tanks, establishing sources and filing freedom of information (FOI) requests.

Another key to getting focused is starting to write the stories early on, Patrucić said.

"The sooner that reporters can outline and write the stories, the better, as it gives editors time to identify missing information and make sure that each individual article fits into a greater whole," she said.

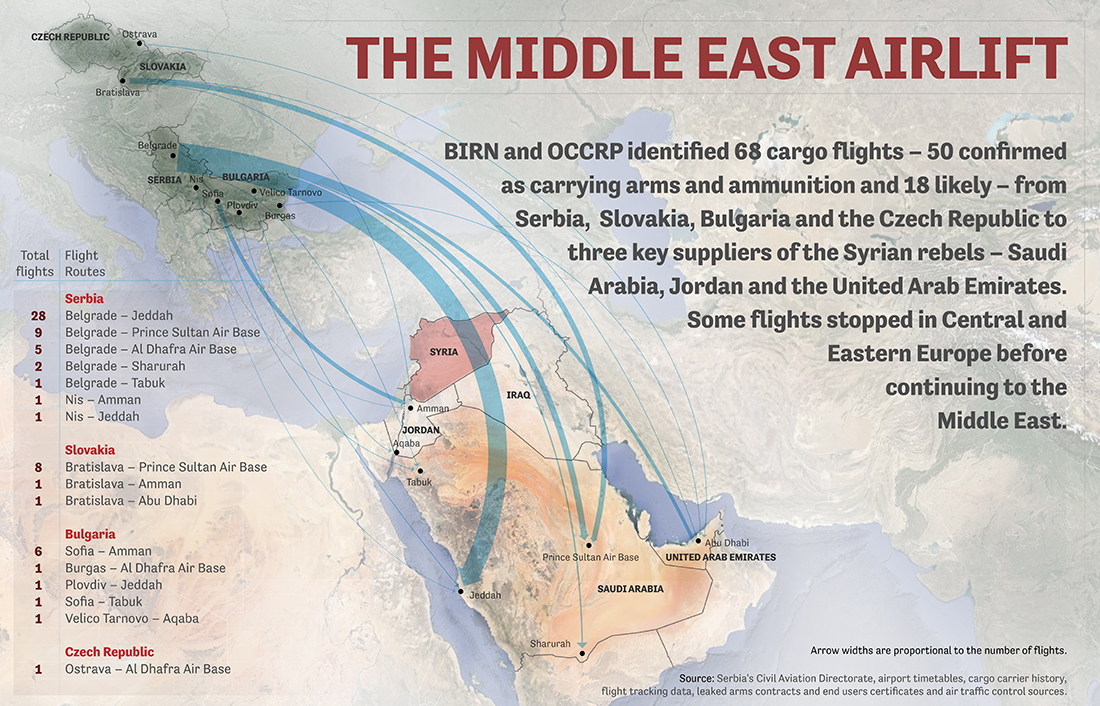

Cross-referencing data sets may also help journalists make connections and further refine story ideas. The "Making a Killing" team had a major breakthrough after comparing a database of cargo flights that pass through Eastern Europe with another database listing flight schedules. This eventually resulted in an article showing how dozens of Eastern European cargo flights have moved thousands of tons of arms and ammunition to the Middle East over the past year.

Graphic produced by OCCRP and BIRN

Communicate frequently — and safely

When working on a transnational investigation, Patrucić recommended having a coordinator responsible for each team of reporters in each country. While OCCRP and BIRN communicated frequently on Slack, Signal and Stackfield, don’t underestimate the importance of frequent, in-person meetings, she said. These meetings help reporters make connections between countries and identify larger trends they otherwise couldn't.

“If you don’t communicate enough, everyone is going to wander off in their own direction,” she said.

Even though OCCRP and BIRN have been competitors in the past, reporters would always tell their colleagues who they were meeting with (without naming sources) and ask if anyone else had any questions they wanted asked.

And when investigating a sensitive topic like the illegal arms trade, reporters should always be thinking safety first, Patrucić said.

“Be careful what time you talk to people, and be careful about who you select as a partner,” she said. “If you have a leak in one country, it could blow up in all the other countries as well.”

Documents as sources

Patrucić estimated that 50 percent of the documents used for "Making a Killing" were found online — especially those published by the United Nations or the European Union — or were given to journalists from other organizations. Another 20 percent of the documents were provided by sources, while 30 percent came from FOI requests.

“[Those documents are] published and available, but few reporters look through all of them,” she said.

Getting officials on the record

Another challenge when investigating the transnational arms trade is getting officials to talk on the record. OCCRP and its partner organization found one way around this by using lower-ranking officials in certain agencies as sources. They also reached out to weapon factories, but had little success finding people willing to be identified.

They had a particularly difficult time trying to get the Serbian civil aviation authority to answer questions. The agency finally relented after BIRN and OCCRP showed them video footage of a cargo plane being loaded with crates of ammunition. Broadly speaking, confronting government officials with video or paper evidence helped reporters get on-the-record comments, Patrucić said.

Meanwhile, government officials in Eastern Europe continue to show little willingness to control arms exports to the Middle East. Several days after BIRN and the OCCRP published "Making a Killing," Serbia’s prime minister said he “adored” arms exports because it brought so much foreign money into the country.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via a.anis.