High-stakes, high-interest events such as protests, riots, wars and natural disasters cause an extremely high demand for news that vetted, reported information can’t necessarily keep up with. Some people in the misinformation space call these “information incidents” or “misinformation crises.” The worldwide spread of COVID in early 2020 is an example of a global, drawn-out information incident.

The Russia-Ukraine war is an especially hazardous example, with a digital information landscape pockmarked with both unintentional misinformation, like misguided social media posts, and intentional, like Russian propaganda.

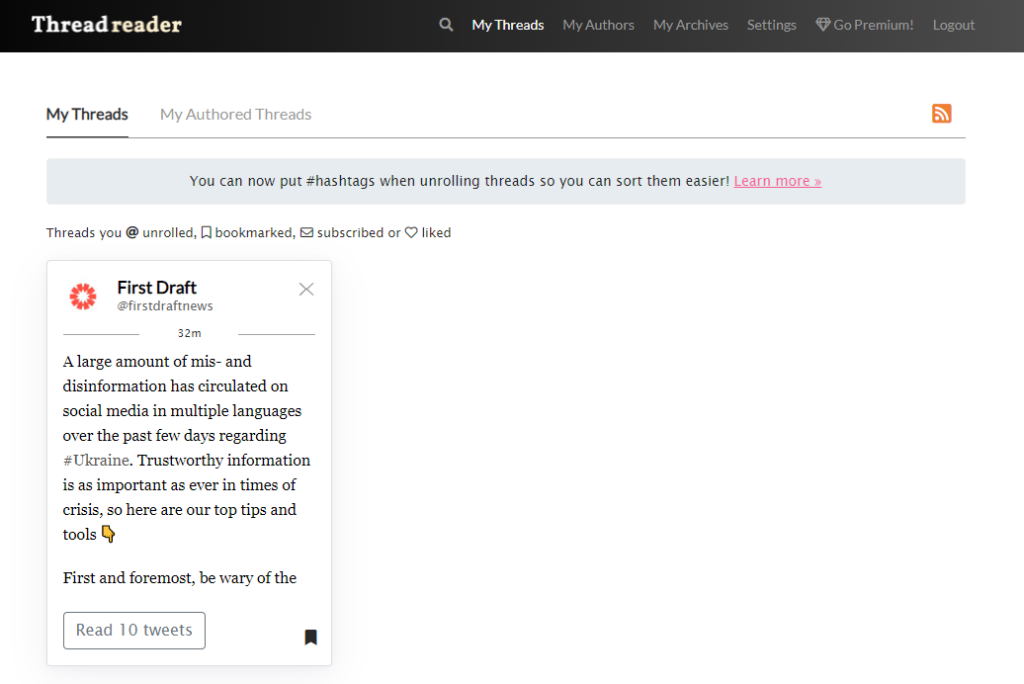

The second type is often referred to as “disinformation,” meaning false information that was knowingly created and disseminated to further a goal. (In casual conversation it is all referred to under the umbrella of “misinformation.”) In a recent tweet thread, journalism educator First Draft News outlined the difference, saying it could affect not just the reporting and consumption of information, but also how players are perceived.

— First Draft (@firstdraftnews) February 28, 2022

The thread shares a range of tips covering images, videos, social accounts and general phrasing for reporting on high-stakes news events. These include tactics that have been covered in previous columns, like RevEye for reverse image searches and the Internet Archive for backing up webpages. The team also suggests creating image overlays, which add text to an image to indicate that it is fake or misleading.

A lot of the guidance and expert advice (or “expert” advice) is coming from social media, like this thread from Bellingcat. To save it, you can use a Twitter add-on called Thread Reader. The add-on works by just tagging @ThreadReaderApp in a reply or a quote tweet of the thread. This creates a webpage that you can bookmark for later, as well as adds it to Thread Reader’s large repository of saved threads. If you didn’t save it in time, you can search for older threads using their search function.

You do have to have a Twitter account to use Thread Reader, because you need to tweet at them. But if you connect your account, the tool gives you a dashboard where you can organize your saved threads using hashtags or your own filing system.

But Thread Reader will only archive a series of tweets — it won’t save an individual post. For the firehose of individual tweets, you may want to use a tool like TweetDeck or InoReader to keep up with it all.

TweetDeck is familiar to many journalists as the central tool for both reading and writing tweets, often from multiple accounts. It’s also one of the most powerful tools out there for finding relevant tweets. For example, it’s one of the only tools that lets you sort or filter results by a minimum number of likes or retweets, allowing you to sift out the many (in some cases, hundreds, or thousands) of tweets that are low-value or low-interest. Just like Thread Reader, the third party tool was bought by Twitter itself, making it easy to integrate your accounts.

Inoreader is a newer tool that creates a dashboard of tweets as well as Facebook posts, Reddit subs, and Google alerts. With a Pro account you can add in Telegram and individual newsletters. If you’re not familiar with Telegram, it’s a popular messaging app outside the U.S., making InoReader especially useful if you are covering on-the-ground information in situations like Ukraine.

News events like the Russia-Ukraine war spawn an inordinate amount of fast-moving information, which of course creates many opportunities for the flow of misinformation. Earlier this year, a fact-checking organization called Full Fact released an updated version of their Framework for Information Incidents — essentially a playbook for governments, internet companies and members of the media facing what Full Fact calls “misinformation crises.”

Instead of listing a series of hands-on tools, like the First Draft News thread, Full Fact provides a thoughtful template for how leadership can think about this crisis, and plan a response. The framework includes a glossary and incorporates research and feedback from other well-respected fact-checking organizations like Chequeado and Africa Check.

A similar tool is the Verification Handbook published by datajournalism.com. Described by other researchers as a “canonical verification resource,” the Verification Handbook is a ready-to-use guide for fact-checking in any breaking news situation, not just ones that are prone to misinformation.

For reporting on the Russia-Ukraine war itself, journalists must also deal with the heightened threat of propaganda (politically-inspired disinformation) in addition to the usual plethora of rumors, statements, claims and arguments issued from social media.

“There has been a huge demand for information on how mysterious Russian trolls and hackers work,” Bellingcat researcher Aric Toler wrote in a 2020 article titled “How (Not) To Report On Russian Disinformation.” “But the output on these subjects too often reverts to hollow cliches and, ironically, misinformation.”

Toler recommends versing yourself in Russian media outlets and assessing social accounts for bot activity before using them as sources for any kind of content. The Stanford Cyber Policy Center published its own Newsroom Playbook for Propaganda Reporting, with tools and policies that can be implemented newsroom-wide.

Even for journalists not covering the Russia-Ukraine war, these guidelines can be applied to many other situations where a government is a player in the misinformation game. Though propaganda is not often the focus of anti-misinformation education, because it is only one small part of the misinformation problem, journalists should try to be prepared.

This article was originally published at the Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri.

Photo by Issy Bailey on Unsplash.