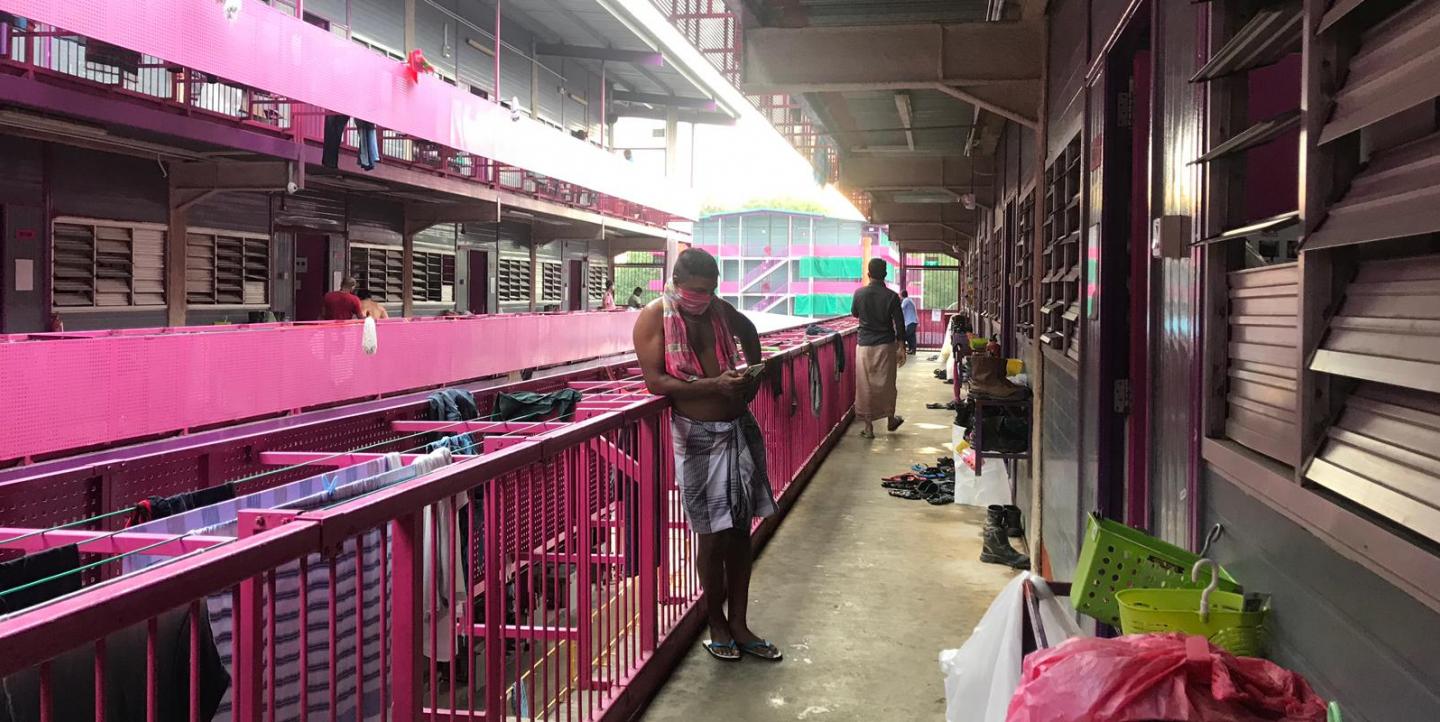

When COVID-19 broke out in Singapore in early 2020, the country shut down. Migrant workers, who make up over 20% of the population, generally live in dormitories. When the country went into lockdown, these workers were isolated in their small rooms with limited access to resources and a constant fear of contracting the virus in close quarters.

Activists have called it Singapore’s greatest humanitarian crisis, and journalists quickly jumped into gear to shine a light on the horrible conditions these workers were in.

Singaporean journalists Toh Ee Ming and Kelly Ng were among the journalists reporting on the topic.

“I wanted to see how I could add to the discourse, but there was an oversaturation of information. We were trying to find a new way to add to the story. At the time, there wasn't much information about the mental health aspect,” said Ee Ming. “We wanted to show the ways that the migrant workers were coping, including some of the more lighthearted ways that they were coping as well besides the bleak conditions.”

[Read more: Covering the pandemic's impact on Haiti's deaf community]

Their story, which documents the stories of migrant workers living in dormitories in Singapore during COVID-19, was published in Southeast Asia Globe in May. It focuses specifically on the psychological toll of isolation and was selected as one of the top stories shared in October in the Global Health Crisis Reporting Forum, a project co-created by IJNet and our parent organization, the International Center for Journalists.

"This story was first and foremost a human story addressing a very real problem only exacerbated by the pandemic. The variety of different angles the reporters covered, including the voices of the migrants themselves, plus the stunning photographs, made it a compelling long-form report," said ICFJ Director of Community Engagement Stella Roque.

Both reporters have covered migrant workers in the past, which allowed them to utilize already established contacts to get in touch with workers in the dormitories where communication can be difficult. The writers also used social media to connect with the migrant worker community that, like others, has turned to technology to keep in touch.

“Because Singapore was on lockdown, we could only communicate with them through texting or calling, which I guess is a little bit regretful in some part,” said Ng. “You really wish you could meet face-to-face.”

[Read more: 12 apps journalists can use to record interviews remotely]

Individuals living inside the dormitories reported feeling like they were in prison due to unsanitary living conditions, poor food quality and isolation. Acknowledging the mental stress these circumstances created — along with anxiety about catching the virus — was a priority for Ng and Ee Ming.

“The pandemic, in general, has just been a very distressing event for many of us, and I guess more so for these low wage migrant workers because it's not a secret that their living conditions aren’t the best,” said Ng. “They were one of the earlier [groups] to be locked down and for even longer periods of time with much more restrictive conditions than the rest of us.”

This story helped the writers shine a light on the plight of the migrant workers, while also demonstrating the workers’ resilience and commitment to one another, which can often be lost in victimizing narratives.

For example, Islam Rockybul, a migrant worker and safety coordinator who was interviewed for the story, hosts video calls with more than 100 workers he oversees and their families to keep in touch. He and his wife in Bangladesh also do video calls to do yoga together.

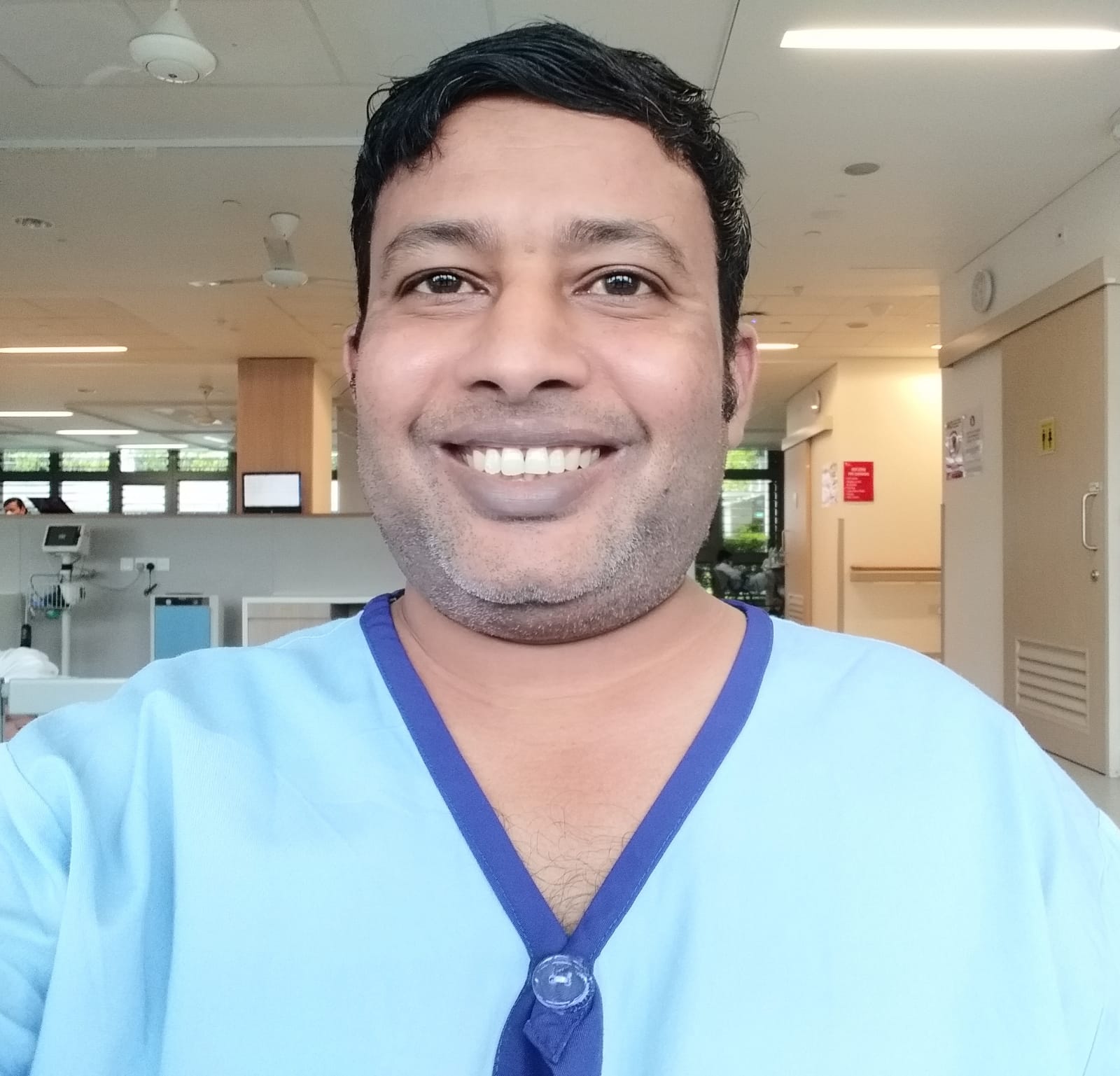

Zakir Hossain Khokan, another migrant worker interviewed for the story, was diagnosed with the virus in April. However, it didn’t keep him from coordinating hygiene product and reading material donations from his hospital bed. Ee Ming interviewed him via voice messages, but she said it was difficult to only be able to send one question and response at a time.

After publication, a friend who works as a doctor for migrant communities encouraged Ng and Ee Ming to compile a list of resources for migrant workers, since information from non-governmental organizations can be scarce. The resulting resource is called Dear Migrant Brothers, and it is available for workers to download via QR code.

Despite the acknowledgment of poor conditions that the workers received during the pandemic, some are concerned that there will be little lasting effect on how migrant communities live inside overcrowded dormitories.

“Many of them mentioned that they felt like the news cycle had moved on,” said Ee Ming. “They feel kind of disillusioned because conditions seem to be back to normal, and they are still crammed into dorms of eight to 20 men, and they are still crammed on the back of lorries.”

She added: “One worker said that he thinks we didn’t learn anything from COVID-19, which was very chilling to me.”

All images in this story are courtesy of Toh Ee Ming and Kelly Ng.

Chanté Russell is a recent graduate of Howard University and a programs intern at the International Center for Journalists.