Proposed reforms of Australia’s national security laws aimed at clamping down on government leaks have raised fears for press freedom in one of the Asia-Pacific’s most open democracies.

The National Security Legislation Amendment Bill 2017, which comes amid a broader crackdown on foreign interference and espionage, would make the communication or handling of sensitive government information a crime punishable by up to 20 years in prison.

Under the changes quietly unveiled by Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s centre-right coalition in December, the law would cover any material obtained through a government official without authorisation and considered “inherently harmful” or likely to harm “Australia’s interests.”

Extending beyond traditional national security considerations, the law would apply to information that could in any way harm international relations or relations between the federal government and any of Australia’s states and territories.

Harsher penalties for whistleblowers

Although public servants are already prohibited from disclosing sensitive information, the reforms introduce far harsher penalties and bring anyone, including journalists, within their remit.

While the legislation contains some protection for journalists, a defense is only available for reporting that is subjectively judged to be “fair and accurate.”

“You really have an expansion of this traditional category of offenses against the state—treason, espionage, things like actually urging the overthrow of a country—and now you’re getting into this realm of sharing information to undermine Australia’s interests,” says Kieran Hardy, a national security and whistleblowing expert at Queensland’s Griffith University.

Civil liberties groups have roundly condemned the push for greater secrecy, warning of the chilling effect the law would have on potential whistleblowers.

“In a post-Snowden and Wikileaks world, it is evident that simply cloaking something as ‘classified’ doesn’t mean it should automatically be free from public scrutiny,” Human Rights Watch wrote in a submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, which is examining the legislation. “Under this Bill, government officials may be tempted to reclassify information with a higher security rating so that it cannot be shared.”

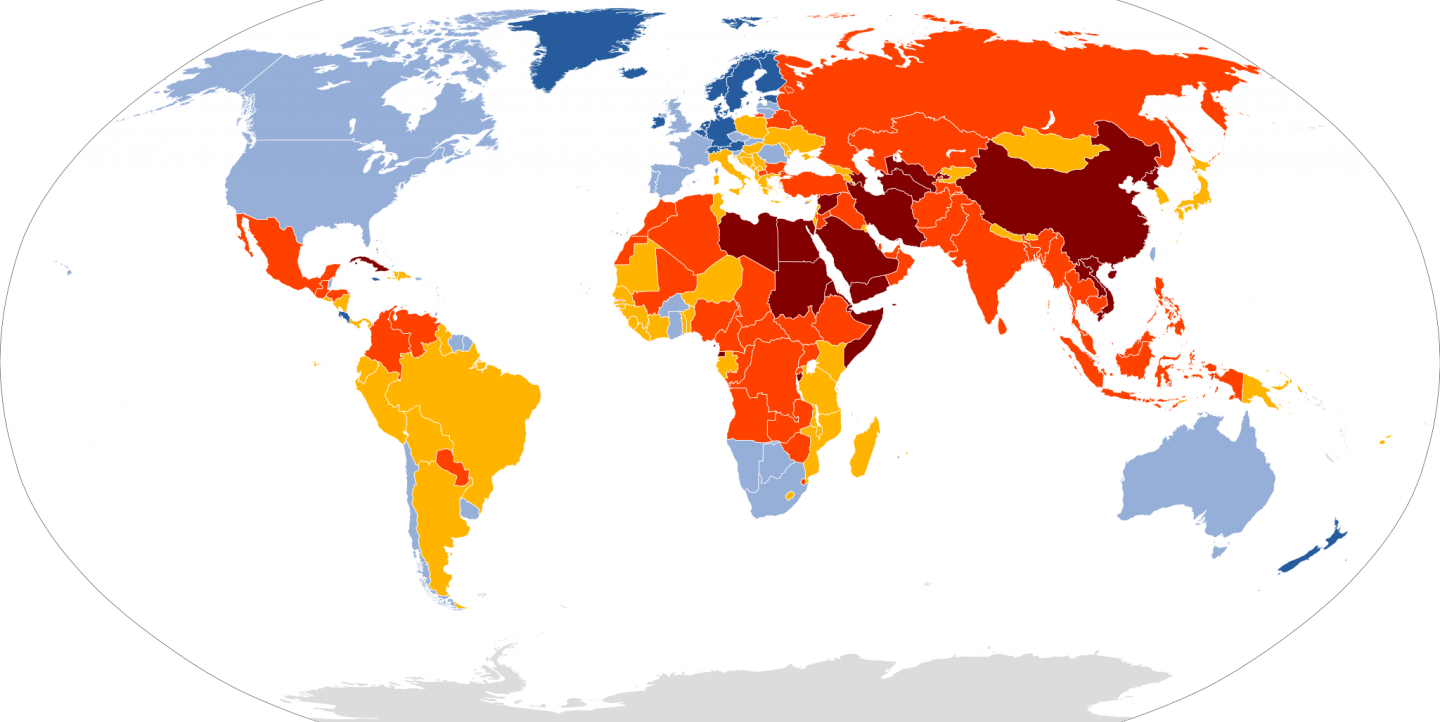

The Australian media have also come out strongly against the proposal. The Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance, the country’s main union for journalists, called it a “dangerous threat to press freedom”. Australia is currently considered to have one of the freest media environments in the Asia-Pacific, with Freedom House last year ranking the country fifth for press freedom after New Zealand and a number of tiny Pacific Island nations.

In a submission to parliament last month, though, more than a dozen Australian rival media organizations made a rare show of unity to warn that the proposed legal changes soon meant that “journalists could go to jail for doing their jobs.”

Since then, international press advocacy groups including the Freedom of the Press Foundation and the Committee to Protect Journalists have joined the chorus of opposition to the changes.

Changes likely to pass

The legislation follows almost five dozen national security related laws introduced in Australia since the September 11 terror attacks which, critics say, have made it increasingly difficult to expose potential wrongdoing.

In 2015, parliament passed sweeping metadata retention laws despite warnings from press freedom advocates that the measures would expose whistleblowers and other confidential sources.

While a public interest disclosure scheme was introduced for public officials in 2013, bringing Australia into line with countries such as Singapore, Japan and South Korea, whistleblower advocates say the current environment is still far from accommodating of those who come forward to expose wrongdoing. Public-servants-turned-whistleblowers, such as former Australian Taxation Office official Ron Shamir, have detailed how going public with their concerns cost them their livelihoods and any prospect of future career advancement.

“The status quo is definitely not conducive to it,” says Hardy. “It’d take a lot of courage in this environment to be putting your name to a leak.”

After the committee stage finishes up in March, this latest piece of contentious legislation will still have to pass both the House of Representatives and Senate. Opposition leader Bill Shorten this week announced that his party would not support the bill without better protections for journalists, joining a growing number of skeptical voices in parliament.

Despite the controversy, though, it’s unlikely that the proposals will see anything other than relatively minor changes. Turnbull’s government, which would have to negotiate with a chaotic cross-bench in the Senate without the rival Labor Party’s support, has history is on its side.

In the last two decades, the vast majority of national security legislation introduced by Australian governments has made it into law with little or no revision.

“No political party wants to be called soft on terrorism, so they’ve traditionally been bipartisan,” says Hardy. “There are very few examples of counterterrorism laws that have gone through the Australian parliament that have been amended as a result of opposition in the Senate.”

This article originally appeared on The Splice Newsroom. It has been republished on IJNet with permission.

Main image CC-licensed by Wikimedia Commons via NordNordWest.