This is the first article in a two-part series examining trends restricting social media access and usage in the Middle East.

For the past 11 years, I have been charting social media trends in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) through a series of annual reports capturing common behaviors, as well as barriers to usage.

These studies began a year after the Arab Spring, a geo-political event that sparked considerable interest in the potential of social networks as agents for change in the region.

Since then, in many MENA nations, we have seen a rapid take-up of digital technologies, coupled with a steady tightening of online creative and political freedoms. That means that although there is tremendous online creativity in the region – look at YouTube’s list of top MENA creators for a myriad of examples – opportunities for artistic expression are far from limitless.

It is one of the world’s biggest digital ironies that despite being among the most active adopters and users of these technologies, many countries in MENA are also among the most restrictive.

Looking back over the past year here are five media freedom trends worth noting:

(1) Curtailing influencers and content creators

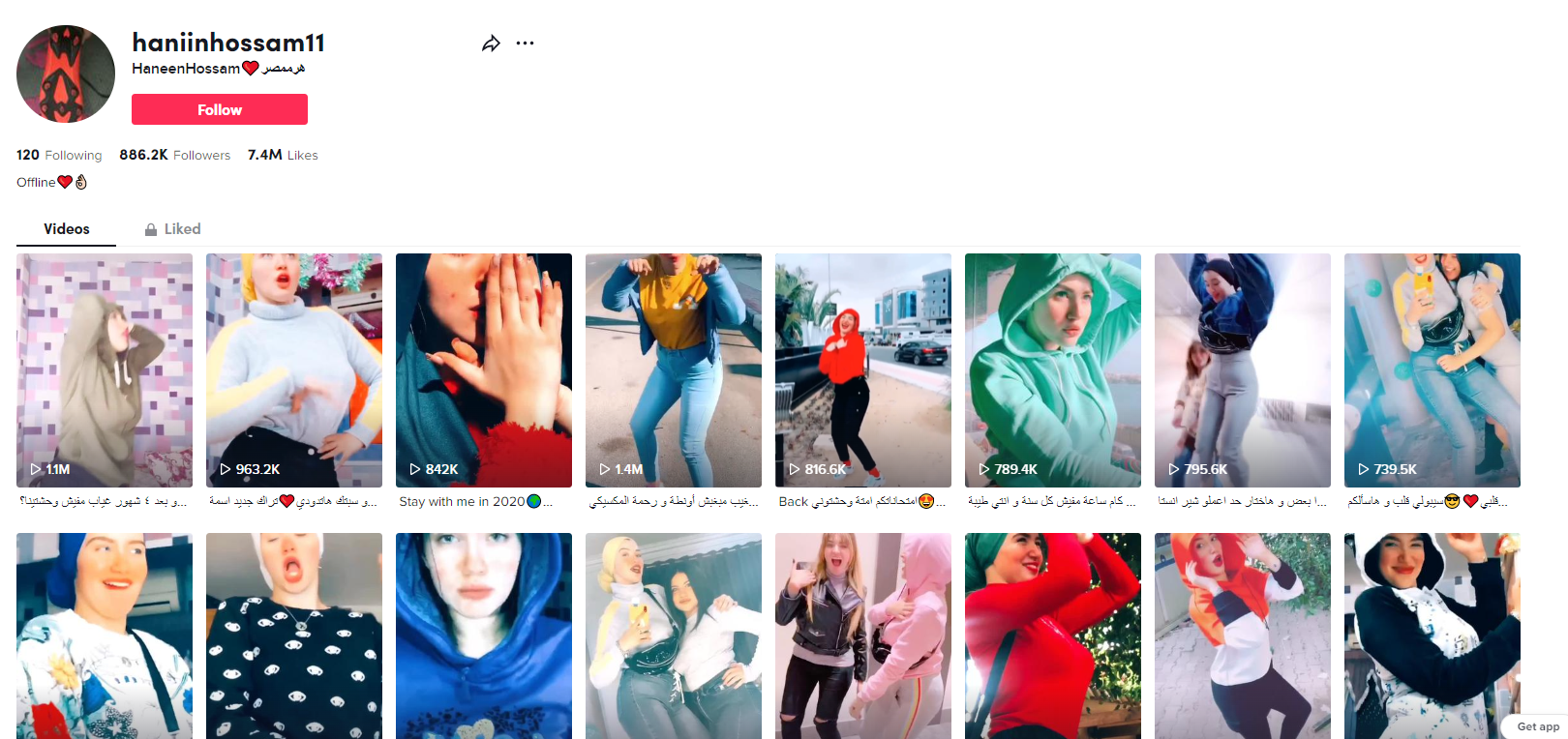

Last year the Egyptian TikTok star, Haneen Hossam, was sentenced to three years in jail and a fine of 200,000 Egyptian pounds (about $10,760) for “indecency,” “violating family principles” and “human trafficking” charges.

Hossam, who had more than one million followers at the time of her arrest, argued that her content was taken out of context.

The BBC notes at least 11 other women with millions of followers have faced similar charges. This includes Tala Safwan, who was arrested in Saudi Arabia and accused of posting sexually suggestive content with lesbian undertones. Another Egyptian TikToker, Ibrahim Malik was arrested in October 2022 on charges of “promoting immoral content.”

These developments are not unique to Egypt. In late September, the Kuwaiti Public Prosecution sentenced two TikTokers for violating public morals. The two female influencers face two years of prison each, and fines of between $6,500 and $16,200. A female Arab Snapchat influencer has been banned from advertising in Saudi Arabia after publishing videos promoting tobacco. The influencer violated laws against promoting smoking, as well as advertising without a license. They were fined SR400,000 (about $106,000).

(2) Arrests and attacks on journalists

Alongside clamping down on creatives and influencers, critics of political leaders can be especially susceptible to restrictions on media freedom.

Blogger and civil society activist Amina Mansour was given a six-month prison sentence by Tunisian authorities last spring after sharing satirical posts on Facebook back in 2021. The Jordanian journalist Adnan Al-Rousan was also arrested last year following critical columns posted on Facebook.

In one post, Al-Rousan wrote that Jordanians "are silent and stifled by anger, waiting for the king to reform himself and abandon festivals, films, trips and conferences and focus on the country." Al-Rousan, 71, was accused of "inciting conflict, sowing division [...] spreading false news that harm the prestige of the state, slandering an official body and humiliating a civil servant," AFP reported.

In Turkey, IFEX shared how reporter Ebru Uzun Oruç, and her partner and cameraman Barış Oruç were attacked on the street following threats from ultra-nationalist groups. This followed a street interview series for Sokak Kedisi TV asking citizens about their opinion of Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahçeli.

(3) Reducing access to content

Turning off the online tap is a common tactic deployed by authoritarian regimes around the world. Iran, for instance, has consistently restricted access to a range of social media and messaging platforms, including Instagram and WhatsApp, during the past year.

As part of these efforts, Radio Free Europe described how Iranian authorities blocked two-step verification codes from social media applications. “This means that if a user in Iran is logged out of the application, it is not possible to log back into the account again,” they explained. In response, platforms such as Meta and Signal produced guides and public statements vowing to keep services working.

And just as TikTok influencers have come under threat, so has the platform itself. Although widely used in the region, Jordanian authorities imposed a temporary ban on TikTok in December 2022, after a police officer was killed during protests over fuel price hikes. The app remains blocked today, with no clear indication of when the ban would be lifted.

(4) Manipulating the conversation

Platform manipulation has been a growing trend in the region, as countries deploy cyber armies to try to control narratives at home and abroad. This can taint what users see online and, in turn, influence what they think, and how (as well as where) they express their opinions.

According to a report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia are the three most “prolific perpetrators” of state-linked disinformation on social media. These efforts don’t just impact users in MENA but often emanate from the region, too.

Meta, for example, removed a network of fake accounts targeting Instagram users in Scotland with content supporting Scottish independence. About 77,000 people followed these Instagram accounts, which originated in Iran. Iranian intelligence officials have also offered Instagram content moderators money to remove the accounts of journalists and activists, BBC News reported.

Dr. Marc Owen Jones, an assistant professor of Middle East Studies and Digital Humanities at Doha's Hamad Bin Khalifa University, shared in a Twitter thread that around 5,000 fake Twitter accounts were being used to dilute the prevalence of Arabic hashtags expressing discontent about the normalizing of relationships between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Thread 1/ During Biden's visit to the Middle East, there was much discussion about #Saudi Arabia and normalisation with Israel. As a result, the hashtag 'millions against normalization trended'. This analysis shows attempts to disrupt that trend with fake accounts #disinformation

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) July 22, 2022

8/ So to sum up. Around 5000 (approx) fake accounts appear to be drowning out an Arabic hashtag designed to express discontent against normalisation with Israel using a technique called hashtag 'chopping' or 'cropping'. #disinformation #palestine #saudi

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) July 22, 2022

(5) Introducing new laws and legislation

Finally, we have also seen the continued use of legal measures as a means to influence media freedom.

Turkey’s parliament adopted a new law that could jail journalists and social media users for up to three years for spreading disinformation. However, the law has no clear definition of what constitutes false or misleading information, Reuters says, raising concerns about freedom of expression.

In a similar vein, Israeli authorities are preparing to pass a bill that, if approved, will allow the government to remove any social media content they believe constitutes incitement or causes harm. Arab News reports the bill will allow authorities to block content on all websites, including news sites.

Alongside these five prominent areas of activity, new threats to media freedom in the region are also emerging and becoming more significant. We will explore those in more detail in the second and final article in this series.

Read more about these issues and wider trends in Social Media in the Middle East 2022: A Year in Review, by Damian Radcliffe and Hadil Abuhmaid with Nii Mahliaire, published by the University of Oregon-UNESCO Crossings Institute.

Main photo by Mariia Shalabaieva on Unsplash.