It wasn’t long after Presidents Obama and Castro announced foreign policy changes in December 2014 that coverage of Cuba began gaining above-the-fold prominence in American media. And it wasn’t long after that before Havana-based journalist Conner Gorry and I began complaining, on Facebook, about the poor quality of much of that coverage.

Gorry and I have been covering Cuba for more than a decade each and have long wanted to see both more prominent and more varied, nuanced coverage of the island in the United States. But as our wish for more coverage was realized, it became evident that 50 years of sour foreign relations made an indelible impact on journalism. From a lack of historical, cultural and social context-informing articles to the seemingly unconscious perpetuation of loaded terminology and outmoded cliches, the gap between what we wanted to see and what we were seeing was wide indeed.

Friends urged us to stop complaining and, instead, to teach what we thought journalists needed to know. We did exactly that on May 1 during a workshop titled “How to Report on Cuba (Responsibly),” sponsored by The Center for Cuban Studies and hosted by The Graduate School of Journalism of the City University of New York. Approximately 20 journalists and students attended the full-day workshop. It was clear that there was deep interest in the subject, with questions and conversation continuing an hour beyond the scheduled end time.

We wanted to keep that conversation going, and to that end, we’re sharing five of our most salient tips here:

Take a crash course in Cuban history.

As Sandra Levinson, director of The Center for Cuban Studies, noted during the workshop, American journalism about Cuba tends to be informed by which interpretation of Cuban history a writer has accepted as fact. Often, however, journalists lack an objective, fact-based understanding of the highlights of Cuban history, especially the years leading up to and following the Cuban Revolution.

For journalists reporting about Cuba, filling in these blanks is crucial. An essential text I’ve found useful over the years is The Cuba Reader, an anthology published by Duke University Press. It includes essential texts by Cubans, as well as those by foreign authors, and is remarkably broad in both temporal and topical scope.

Avoid cliches.

Glance at almost any article about Cuba and you’ll see the same recurring cast of cliches: “frozen in time”; the use of “dictator” and “regime”; “forbidden island”; and “Cuba is finally opening up.” None of these phrases are accurate or precise, and all are lazy. Push yourself to describe the island and its people in other ways and you’ll distinguish your reporting.

Look beyond Havana.

Most reports coming out of Cuba are filed from/about Havana, the capital. As is the case elsewhere, one big, important city should never be a stand-in for the rest of the country. Besides, there are thousands of stories just waiting to be told in Cuba’s provinces and much less competition to tell them.

Collaborate with local journalists.

Teaming up with a local journalist or blogger can be an invaluable strategy for telling better, deeper \stories about Cuba. You’ll learn of subjects and sources that would otherwise be inaccessible to you, and you’ll be made aware of biases and assumptions that might otherwise go unnoticed. Consult our list of Cuban bloggers, all trained journalists, for ideas about how to make local contacts.

Try to exert influence over images.

The cliches about Cuba aren’t limited to text; some of the most persistent stereotypes are those found in photographs of Cuba published in the American media. Cuba is more than old cars and cigar-smoking locals hanging out by the sea. While writers don’t always have control over the images that appear with their articles, it doesn’t hurt to include photo and illustration suggestions to accompany your text. Again, local photographers can be a valuable resource here, with a wider range of images that may be available from usual suspect sources, such as stock agencies. Some of these local photographers and agencies include Cuba Absolutely Photography, Cuba-Photo, Sven Creutzmann, Michael Dweck, Lisette Poole and Robin Thom.

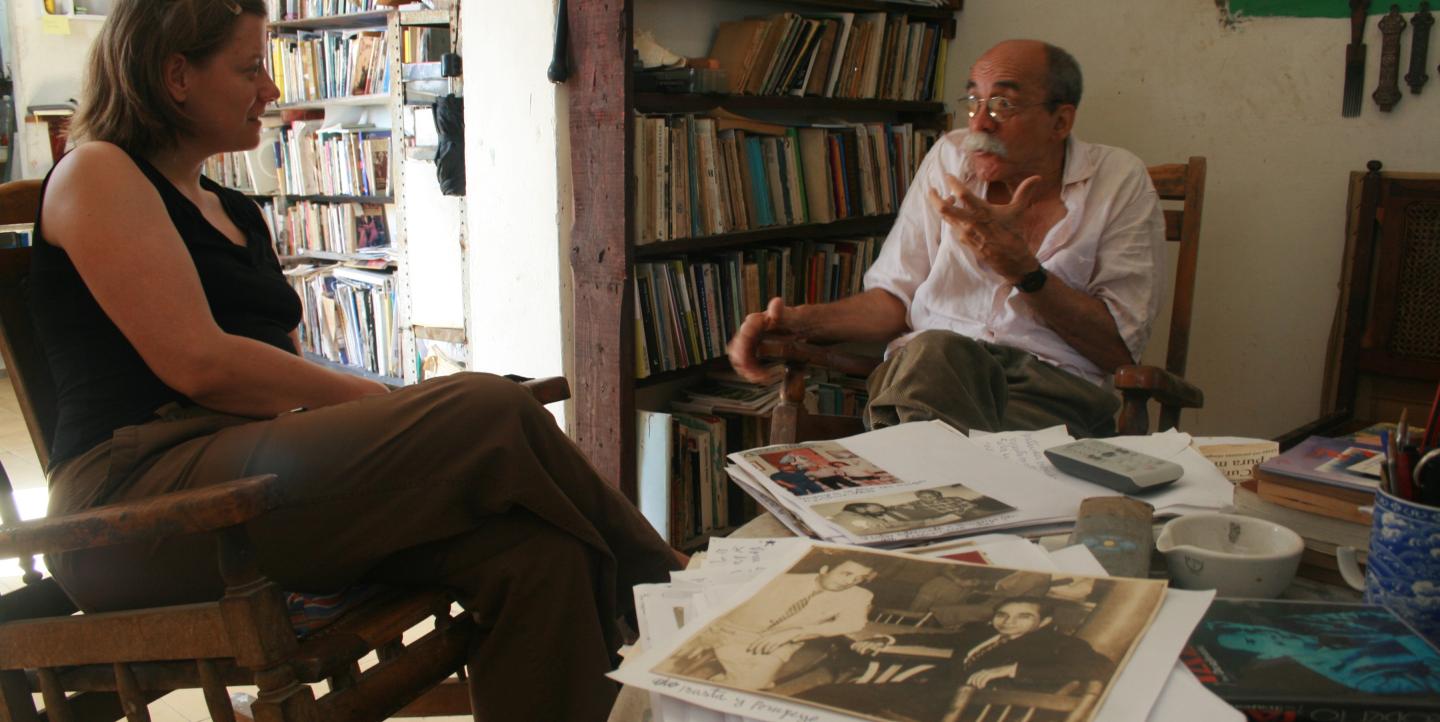

Image of Schwietert Callazo (left) speaking to musicologist in his home in Havana, taken by Brayan Collazo and used with permission.