Once a day, the @Quiztime Twitter account posts an image. It might show an empty street, rolling hills or a plane parked on a runway. It’s usually a photograph, sometimes a video — but it’s always mysterious. And that’s the whole point: By scouring the image for clues, the quiz players, many of whom are journalists, try to figure out precisely where in the world it was taken.

Quiztime began in 2017 when German journalist Julia Bayer posted a photo on her Twitter account showing a rainy intersection in Cologne and asked: “Where am I? Find the exact location.” She did this for the benefit of students in a training session that she was preparing to teach, but suddenly, she saw her Twitter mentions blow up. Her followers had started trying to solve the challenge.

Where am I? Find the exact location. #VerificationTraining #FunLearning pic.twitter.com/OvemUeIzFF

— Julia Bayer (@bayer_julia) March 6, 2017

“At first, I thought, ‘Oh no, the students in my class might see the solution!’” Bayer recalls. “But it was really fun to see people start working on the challenge together, and I thought, why not continue?”

Bayer started posting a quiz every Monday, and soon, she invited some of the players to pick up shifts on other days of the week. The current lineup of quizmasters includes several German journalists, an investigative journalist for Bellingcat and an OSINT expert. On Sundays, anyone from the public can post their own quiz, and Quiztime’s bot will relay it to the community.

“I travel a lot, and I always have my eyes open for pictures that I can take and store for future quizzes,” Bayer says. “I’ll see the sunlight hitting a specific building and think: I’ll ask players at what time I took the picture. I might also leave traces, for example by publishing something on my Instagram account that they can connect to the quiz.”

Bayer says the players usually include a mix of journalists and OSINT experts looking to hone their geolocation and verification skills, as well as people who are just plain curious and enjoy solving puzzles.

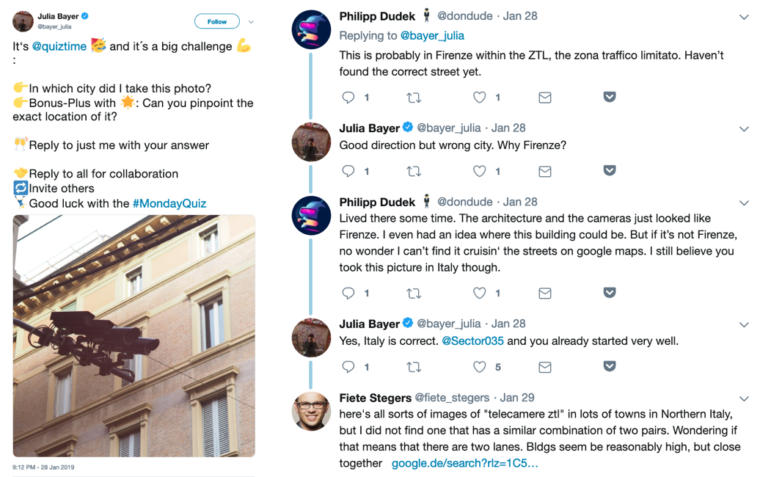

Here’s how Quiztime works: The quizmaster tweets an image, usually one they have taken themselves, along with one or several questions. Sometimes, it’s as basic as asking for the location, date and time. Often, however, the questions get more creative. The core crew of Quizzers is always tagged so that they can help others out.

It’s @quiztime! (A late #ThursdayQuiz) How are the location of this window and a British band connected? pic.twitter.com/QY3vDPHD5t

— Christiaan Triebert (@trbrtc) February 22, 2019

Players who want to discuss clues and collaborate on the challenge can “reply to all.” They might, for example, track down a store logo, identify a tower in the distance or examine the angle of shadows. Usually, it’s not just one clue but rather a combination of clues that will lead them to the correct answer. Along the way, the quizmaster often interacts with the players to let them know if they’re on the right track.

Those who have figured out the answer reply directly the quizmaster, so as not to spoil the game for everyone else. This means that players can start working on a quiz at any time, even after others have solved it. Meanwhile, those who don’t have time to do the quiz can peek into the conversation to read players’ explanations of how they solved it.

“Technique is much more important than tools. Many people know about tools, but not many people know how to use them well.” —Mohamed Kassab

Quizzes vary in difficulty. Some have been solved within minutes, others took hours or days and a few have never been solved at all. (Unsolved cases are listed here.)

“With some images, at the beginning, it doesn’t look like there’s anything in them,” Bayer says. “But there’s always something, a little hidden clue. It’s about training your eyes to see them.”

Mohamed Kassab, an Egyptian journalist who has been playing Quiztime since the very beginning, says that he and other players use all sorts of online tools — like Google Images (or, increasingly, Yandex) for reverse image searches, Suncalc to calculate the time of day, etc. — but cautions that tools will only get you so far.

“Technique is much more important than tools,” Kassab says. “Many people know about tools, but not many people know how to use them well. And when a tool doesn’t work, how else can you arrive at the answer? Through practice, and by summoning all your accumulated knowledge, you start spotting clues and pathways that you wouldn’t have seen before.”

Kassab now uses what he has learned to train other journalists in Egypt and the Middle East. He says these skills are much needed in order for journalists in the region to be able to verify videos and debunk cases in which images are circulating with false information.

“There’s such a collaborative, friendly spirit with Quiztime,” Kassab says. “I’ve learned so much by interacting with the quizmasters and regular players, who are very generous with their knowledge.”

Another regular is Polish journalist Beata Biel. She’s noticed that with Quiztime, there is rarely just one road to the answer.

“There was a quiz for which I used a rather surprising search query, ‘rock like elephant butt,’ and got a way better result that players who were using more elegant queries like ‘boulder with crack,’” Biel said. “And in other cases, I found the answer using descriptive search queries while others found it using a reverse image search. So I find that observing what approach others take can be really interesting.”

Hey, it's #TuesdayQuiz! 👇

— Marc Krueger (@kollege) June 12, 2018

1) What the h... is this?

2) Where is this?

3) Why is this there?

4) Anything spectacular about this?

🧐 Reply to all for collaboration

👉🏼 Reply to me with solutions

🔁 Retweet to invite others

🤘 Follow @quiztime for daily #verification pic.twitter.com/Qd6089uOUF

For Biel, Quiztime is about training her brain in a useful way: “I could be playing Sudoku, but that wouldn’t bring me additional skills I can use in my journalistic work.”

“The quizzes strengthened my belief that you can do a lot of good with these kinds of skills.” — Beata Biel

As an example, she points to a visual investigationpublished by BBC Africa Eye that looked into the killing of two women and two young children by Cameroonian soldiers. By analyzing footage of the scene, which had been dismissed by Cameroon’s government as “fake news,” the journalists established where the killing took place and who was responsible. They examined clues like the outline of mountains in the distance and the angle of shadows. During their investigation, they were helped by a number of Twitter sleuths, including members of Bellingcat and regular Quiztime players.

“A friend of mine asked me, ‘Why are you trying to discover where this video was taken? You’ve never been to Cameroon,’” Biel says. “And that was true. But I also knew that it’s possible to discover a lot just through various clues visible in a video, using even the simplest free digital tools. The quizzes strengthened my belief that you can do a lot of good with these kinds of skills.”

While these skills are often used to document human rights abuses, Quiztime itself never involves investigating violent or disturbing images. This, Bayer says, is by design.

“Some of us are working in daily news, which can be exhausting, so we want this to be about having fun,” Bayer says. “I think that’s also what our users appreciate: that they can be sure they won’t come across any traumatic images here.”

Quiztime is open to anyone who wants to play. All you need is a Twitter account. Biel has some final words of advice:

“Even if you’re too shy to suggest your answer publicly, that’s OK, you can keep it to yourself and look at how others tried to reach the solution. You’ll find that these skills may come in handy very quickly, like when a source sends you a photo or you see a photo online and you have to verify where it was taken.”

Further reading and case studies from the Quiztime blog:

- “Quiztime: The One That Got Me Started”

- “Shadows and Suncalc: Calculating Time Using Clues in a Photo”

- “Comparing the Same Geolocation on Different Map Services”

- “How to Tell the Geolocation of Places Based on Old Sources Using OSINT — A Case Study”

This article was originally published by GIJN. It was republished on IJNet with permission.

Gaelle Faure is GIJN’s associate editor. Previously, she worked for France 24, where she specialized in social newsgathering and verification. She has also worked as an editor for News Deeply and reported for Time Magazine.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Charlotte Butcher.