Когда группа журналистов из Латинской Америки начала расследовать деятельность коста-риканской компании Constructora Meco, их выбор сразу же пал на платформу NINA.

Просто введя название компании в поисковую систему этой платформы, они обнаружили информацию о сложной сети денежных операций и государственных контрактов в нескольких странах региона — не только в Коста-Рике, но и в Панаме, Колумбии, Никарагуа, Сальвадоре, Гватемале, Гондурасе и Белизе. Так родилось совместное расследование под названием Tras los pasos de Meco ("По следам Meco"), в котором приняли участие CRHoy, Foco Panamá и El Espectador в сотрудничестве с Латиноамериканским центром журналистских расследований (CLIP — аббревиатура испаноязычного названия).

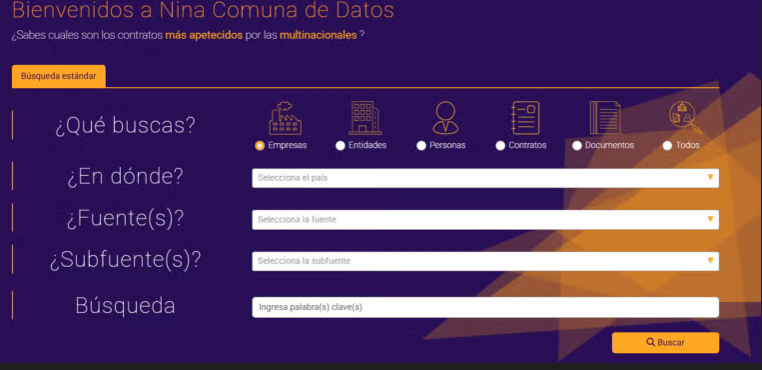

"Платформа NINA исследует различные открытые базы данных и находит связи между компаниями и частными государственными подрядчиками в Латинской Америке", — сказала в разговоре с LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) Эмилиана Гарсия, генеральный директор CLIP.

Команда платформы NINA заявляет, что их проект призван помогать журналистам-расследователям во времена, когда журналистика в Латинской Америке переживает кризис, среди причин которого, в частности, называют нехватку финансирования и ограничения, накладываемые на независимую прессу. Разработанная CLIP платформа дает журналистам доступ к открытым базам данных о контрактах, компаниях и санкциях из 21 страны мира и позволяет сопоставлять важную информацию, выявляя возможные коррупционные сети и другие нарушения и помогая репортерам экономить время и ресурсы.

"Мы советуем журналистам ежедневно использовать этот инструмент. То есть каждый раз, начиная расследование, стоит заходить на платформу и проверять, не найдется ли интересующей вас информации", — сказала Гарсия.

Например, директор и редактор гватемальского сайта No Ficción Освальдо Эрнандес рассказал LJR, что его команда все лучше осваивает поиск информации с помощью NINA и использует этот инструмент для поиска идей расследовательских проектов.

"В одном случае с помощью NINA мы смогли подтвердить, что у юридического представителя компании действительно были связи в системе муниципальных закупок, — сказал Эрнандес. — В итоге нам пришлось отказаться от этого расследования, так как мы не смогли подтвердить нашу первоначальную гипотезу. Но мы установили, что у этого человека действительно были такие связи".

Журналисты также использовали NINA в трансграничных расследованиях, посвященных конфликтам, связанным с добычей лития в Чили и Аргентине, и для подготовки расследования, посвященного "цифровым наемникам" — людям, распространяющим перед выборами мизинформацию на важные для региона политические темы.

Как использовать NINA

NINA опирается на базы данных таких организаций, как OpenCorporates, Open Sanctions, Poderopedia Venezuela, Центр по исследованию коррупции и организованной преступности (OCCRP) и других. Платформа также подключается к государственным реестрам и внутренним базам данных различных СМИ, например к базе данных государственных закупок, созданной Ojo Público в Перу.

Для доступа к NINA необходимо зарегистрироваться и указать информацию о СМИ, в котором работает журналист, страну проживания и гражданство. После входа в систему пользователи получают возможность просматривать данные о компаниях, организациях, людях, контрактах и документах. В настоящее время на платформе зарегистрировано 400 пользователей.

Инструмент позволяет просматривать структурированные данные, организованные в таблицы. Также доступны такие неструктурированные данные, как изображения, PDF-файлы, документы Word, электронные письма и другой контент.

Кроме того, NINA предлагает возможность использовать интерфейс прикладного программирования (API), с помощью которого пользователи могут выполнять поиск с собственных платформ. Однако для этого необходимо получить разрешение команды CLIP, так как доступ предоставляется только журналистам и исследователям.

Члены команды CLIP также бесплатно консультируют журналистов, которые хотят сверить имеющуюся у них информацию с данными NINA, но не обладают необходимыми для этого техническими навыками или финансовыми ресурсами.

Экономия времени и денег

Сегодня журналистика переживает невиданный ранее кризис устойчивости, сталкиваясь с принятием законов, ограничивающих деятельность независимых СМИ, низкими зарплатами, приостановкой иностранной помощи, тем, что многие журналисты вынуждены работать в изгнании, заниматься другой деятельностью и т. д. Поэтому инвестиции в технологии — одна из наименее насущных потребностей сегодняшних латиноамериканских СМИ.

В последние пять лет команда CLIP активно занималась усовершенствованием платформы NINA, следуя своей миссии — способствовать развитию трансграничного сотрудничества и обеспечивать доступность технологий для использования в интересах местной журналистики.

"Работа над первой версией проекта NINA была завершена в 2020 году, но с тех пор мы внесли много улучшений: например, добавили новые данные и усовершенствовали интерфейс проекта, — говорит Гарсия. — И это помогло продвижению многих расследований в Латинской Америке".

Проект CLIP создал NINA на деньги гранта, полученного от Google News Initiative. Разработка, создание и запуск инструмента заняли около года и обошлись в 150 000 долларов США.

Эта сумма не включает выплаты сотрудникам и последующее обслуживание. По словам Гарсии, для поддержания работы платформы требуется от 3 000 до 4 000 долларов в месяц.

"Разработка технологий — дело дорогое, потому что нужно платить за сервер, за память, за скорость, — пояснила Гарсия. — Чем больше пользователей, тем больше поисковых запросов. Иными словами, большее количество запросов требует других скоростей и нагрузок на сервер, а значит, приходится больше платить".

NINA также включает данные из базы данных Sayari, предоставляющей доступ к государственным реестрам, финансовой информации и структурированным данным о бизнесе миллионов компаний по всему миру. Для индивидуальных пользователей доступ к Sayari платный (платить приходится в долларах США), однако CLIP платит за ежегодную подписку и бесплатно предоставляет доступ сотрудничающим с ней журналистам.

NINA помогает экономить не только деньги, но и время. Одна из новых функций платформы — чат-бот на основе ИИ, который выдает более точные и проанализированные результаты. Это позволяет журналистам быстрее продвигаться в своих расследованиях, экономя время, необходимое для чтения документов.

Алехандра Гутьеррес рассказала LJR, что до появления этого инструмента ее команде приходилось заходить в каждую базу данных по отдельности. Теперь они могут за считаные минуты сопоставлять информацию из разных источников.

"Мы сэкономили массу времени, которое уходило на поиск документов, — сказала Гутьеррес. — Теперь, благодаря включению в проект данных по гватемальским организациям, все источники информации собраны в одном месте".

Фото: Markus Winkler с сайта Unsplash.

Эта статья была опубликована на сайте LatAm Journalism Review и публикуется IJNet по лицензии Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.