Depois de receber uma informação sobre atividade madeireira insustentável em uma plantação de palma de óleo administrada pelo governo, Low Choon, ex-bolsista do programa Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), deu início a uma investigação que durou um ano e revelou "o fracasso da plantação, os impactos ambientais e múltiplos empréstimos de um banco local".

"A investigação expôs a fraqueza estrutural da gestão de florestas na Malásia", diz. "Apesar dos vários compromissos ambientais e promessas feitas pela indústria local de palma de óleo, o caso provou que o mau monitoramento e fiscalização do governo, junto com as inconsistências entre diferentes ministérios, permitiu que infratores agissem com impunidade."

Em 2015, a estatal Perbadanan Kemajuan Negeri Pahang (PKNP) começou a plantar palma de óleo em Hulu Tembeling, Jerantut, Pahang, próximo ao Parque Nacional Taman Negara, uma área de floresta densa e madura com biodiversidade rica, porém frágil. Quando Choon Chyuan visitou o lugar em 2023, ele testemunhou a má gestão em larga escala — o projeto era usado majoritariamente para desmatar a floresta.

Neste artigo, Choon Chyuan explica como se preparar para produzir uma reportagem ambiental usando QGIS e imagens de satélite, monitorar movimentos com um aplicativo para celular, acompanhar a cadeia de suprimentos da palma de óleo e descobrir financiamentos de projetos.

Entendendo o projeto e seu entorno

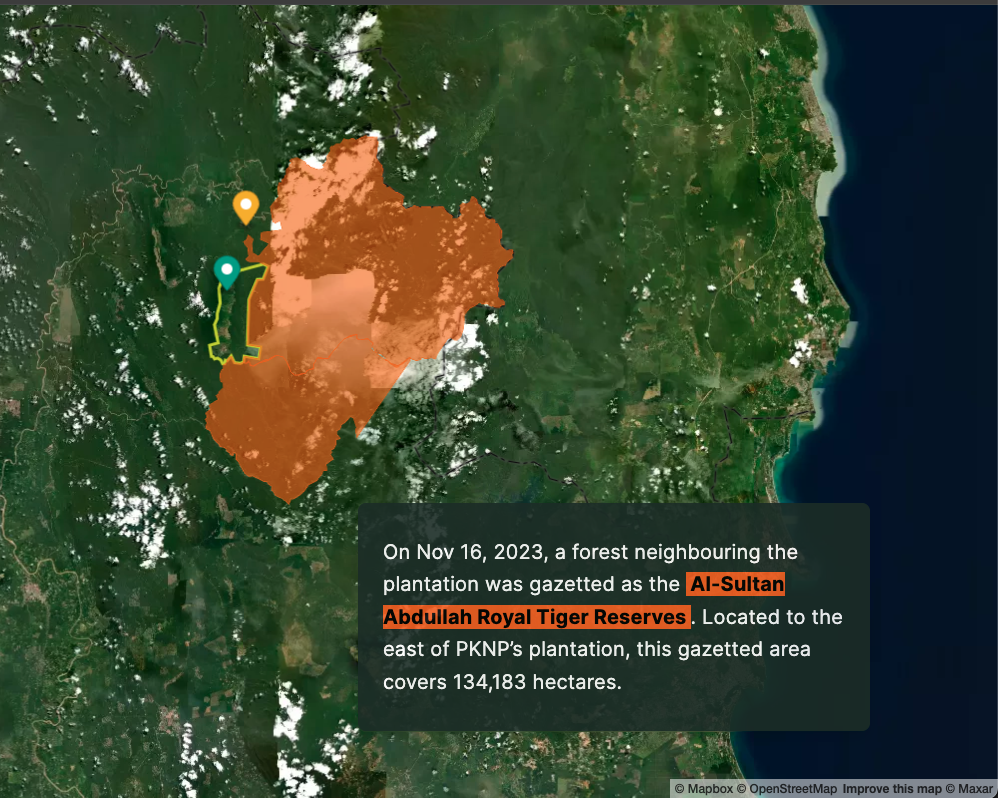

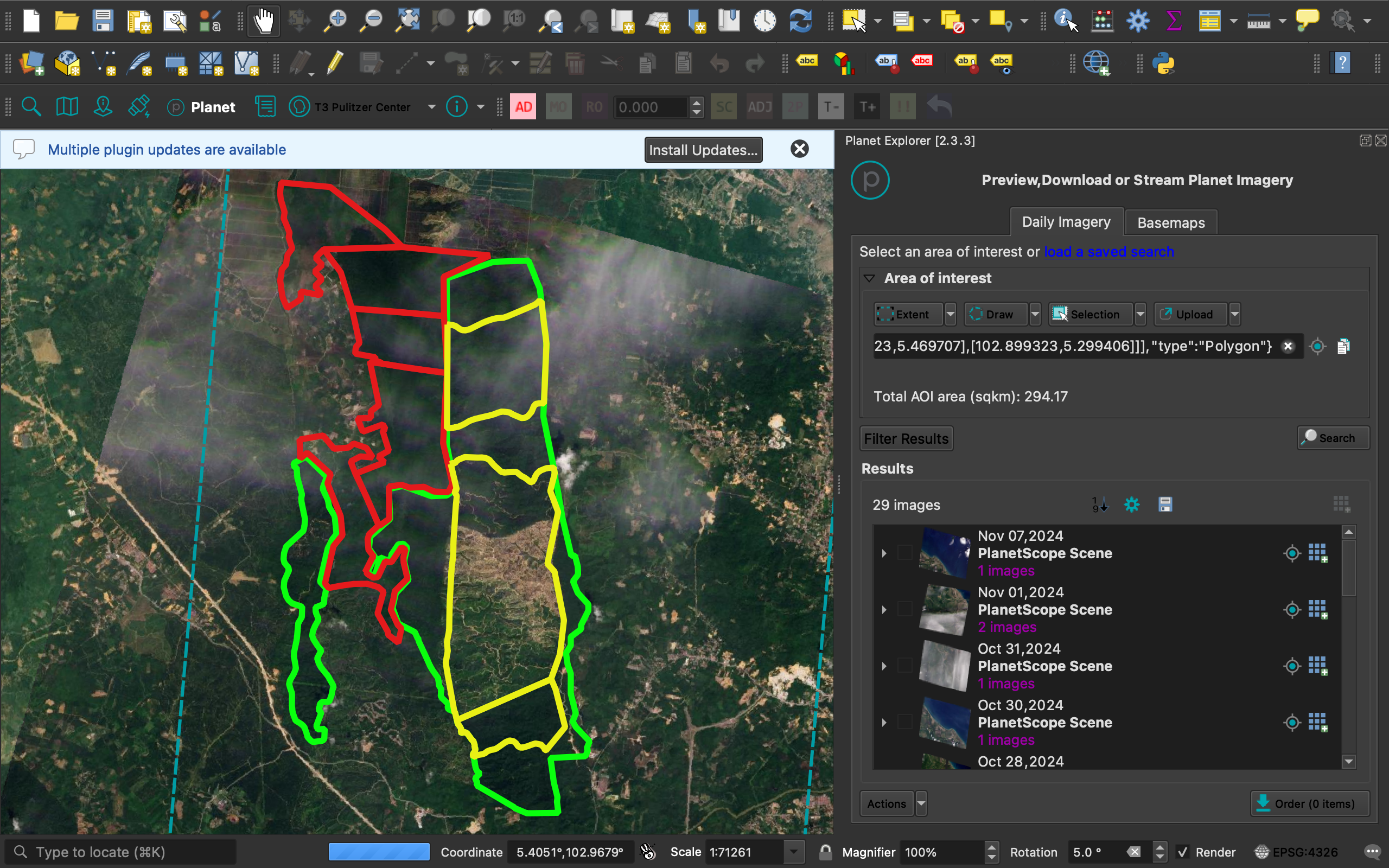

Antes de ir para campo, nós queríamos saber a localização e o tamanho exatos do projeto de plantação da PKNP. Nós descobrimos os limites geográficos do projeto no relatório de avaliação de impacto ambiental (EIA), que conseguimos através de uma fonte. Usamos o QGIS para georreferenciar a área do projeto e compará-la com imagens de satélite para ver se o desmatamento estava ocorrendo fora da área do projeto.

Para entender o entorno da área do projeto, eu pesquisei a existência de algum zoneamento federal, como uma reserva florestal, área de proteção, áreas ambientalmente sensíveis ou represas. A plataforma Rimbawatch, focada na vigilância do meio ambiente, publicou uma lista de dados contendo arquivos de mapas dessas áreas protegidas.

Nós descobrimos que o Parque Nacional Taman Negara e o parque estatal da reserva de tigres estão localizados bem próximos à área do projeto. A demonstração visual da proximidade do projeto com as áreas protegidas é muito potente. Eu usei o QGIS e o Google Earth Pro para analisar e mapear esses dados.

Pesquisa de imagens de satélite

Utilizando o plugin Planet Explorer no QGIS, nós mapeamos o desmatamento na área do projeto de 2019 a 2023. Escolhemos 2019 porque, caso uma plantação de palma de óleo malaia estivesse envolvida em desmatamento após 31 de dezembro de 2019, ela perderia a certificação Palma de Óleo Sustentável Malaia (MSPO), uma exigência para vender a palma de óleo legalmente.

Coleta de dados na viagem de campo

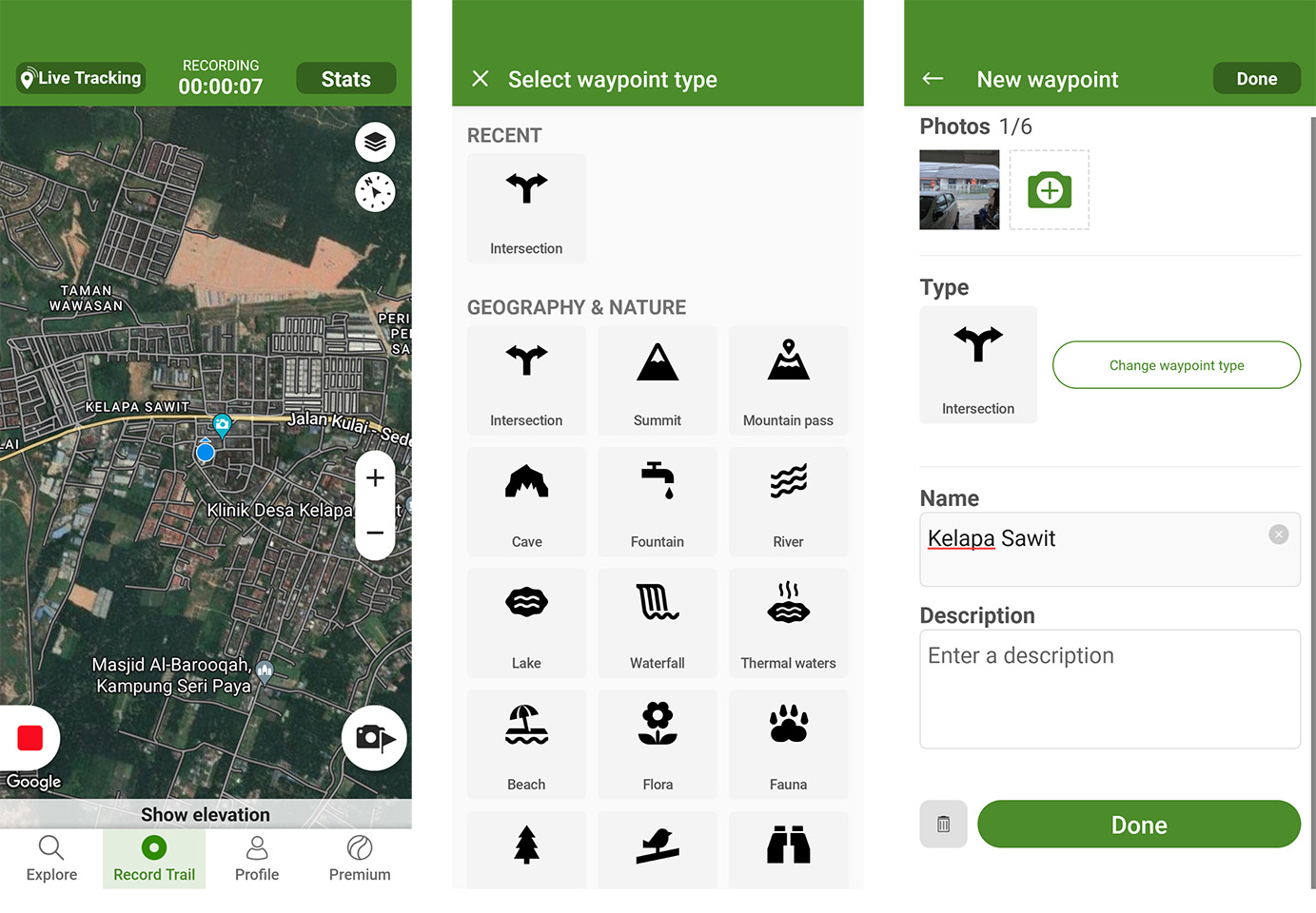

Depois de concluir o trabalho de pesquisa documental, visitamos a área do projeto. Alinhar a pesquisa online com reportagem de campo foi valioso porém desafiador, principalmente na hora de fazer a geolocalização de eventos e observações nos mapas digitais.

O Wikiloc é um aplicativo de navegação para quem faz caminhadas, mas eu o utilizei para registrar minhas rotas durante a viagem de reportagem mesmo quando meu telefone não tinha sinal ou Wi-fi. Na sequência, eu exportei os dados para o QGIS e comparei os lugares por onde passei com a área do projeto.

Eu cruzei os dados que obtive na viagem de campo com imagens de satélite. Por exemplo, um morador me contou que a exploração de madeira havia devastado a vida aquática de um rio. Usando imagens de alta resolução do Earth Genome, parceiro do Pulitzer Center, nós confirmamos que a plantação tinha devastado a região ribeirinha, violando o próprio EIA do projeto e padrões da indústria.

Monitoramento de mudanças na floresta usando o GFW

Eu também subi os dados do projeto para o Global Forest Watch (GFW) e habilitei notificações para alertas de incêndio e mudanças na floresta. Isso me ajudou a seguir acompanhando se a exploração de madeira continuava, ver a frequência e monitorar a área que tinha sido desmatada.

Rastreio da cadeia de suprimentos

Depois, eu pesquisei para onde ia a palma de óleo.

Descobri a Palmoil.io, uma base de dados de plantações locais, proprietários e informações sobre a cadeia de suprimentos. No entanto, não encontrei muitas informações sobre a PKNP porque a produção tinha um rendimento muito baixo.

O MSPO, organismo malaio de certificação, tem um site chamado MSPO Trace, cujo objetivo é oferecer a possibilidade de rastrear produtos extraídos da palma de óleo. Encontrei um relatório de auditoria sobre a plantação PKNP afirmando que a plantação tinha uma performance muito baixa em comparação à safra média de palma de óleo da região peninsular da Malásia.

De acordo com o relatório, "quase 90%" da colheita na área havia sido danificada pela invasão de elefantes. Isso estava alinhado com o que eu havia descoberto em campo: embora a empresa alegasse que queria desenvolver uma plantação de palma de óleo para impulsionar a economia local, ela demonstrava pouco interesse em administrar a plantação após extrair madeira das florestas.

Descobrindo quem financia

Na pesquisa sobre o perfil corporativo da PKNP, descobri que a empresa tinha um empréstimo com um banco malaio para apoiar a plantação em Hulu Tembeling, de acordo com a resposta dada a uma auditoria financeira em 2017.

Para descobrir mais informações, eu precisava dos relatórios anuais da PKNP. No entanto, na Malásia, relatórios de empresas ligadas ao governo (GLC) não são públicos. Os relatórios de empresas GLC federais ficam temporariamente sob poder do parlamento, enquanto relatórios de empresas GLC estaduais ficam sob poder da assembleia estadual.

Consegui os relatórios com um funcionário da assembleia e os documentos mostraram que o Banco Islam, da Malásia, estava financiando o projeto de plantação por meio da filial da PKNP, a PKNP Agro Tech Sdn Bhd (PASB), uma empresa de responsabilidade limitada.

Na sequência, eu comprei relatórios financeiros auditados da PASB em uma base de dados do governo chamada My Data SSM. Os documentos mostraram que o Bank Islam emitiu empréstimos totalizando o equivalente a US$ 11,650 milhões entre 2015 e 2023. Graças ao apoio do Pulitzer Center, eu tinha feito um curso online sobre finanças para entender documentos financeiros de empresas, que me ensinou como analisar relatórios financeiros e identificar sinais de alerta.

Foto por Feyza Bastık.

Este artigo foi publicado originalmente pelo Pulitzer Center. Esta versão editada foi publicada na IJNet com permissão.