In partnership with our parent organization, the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), IJNet is connecting journalists with health experts and newsroom leaders through a webinar series on COVID-19. The series is part of the ICFJ Global Health Crisis Reporting Forum.

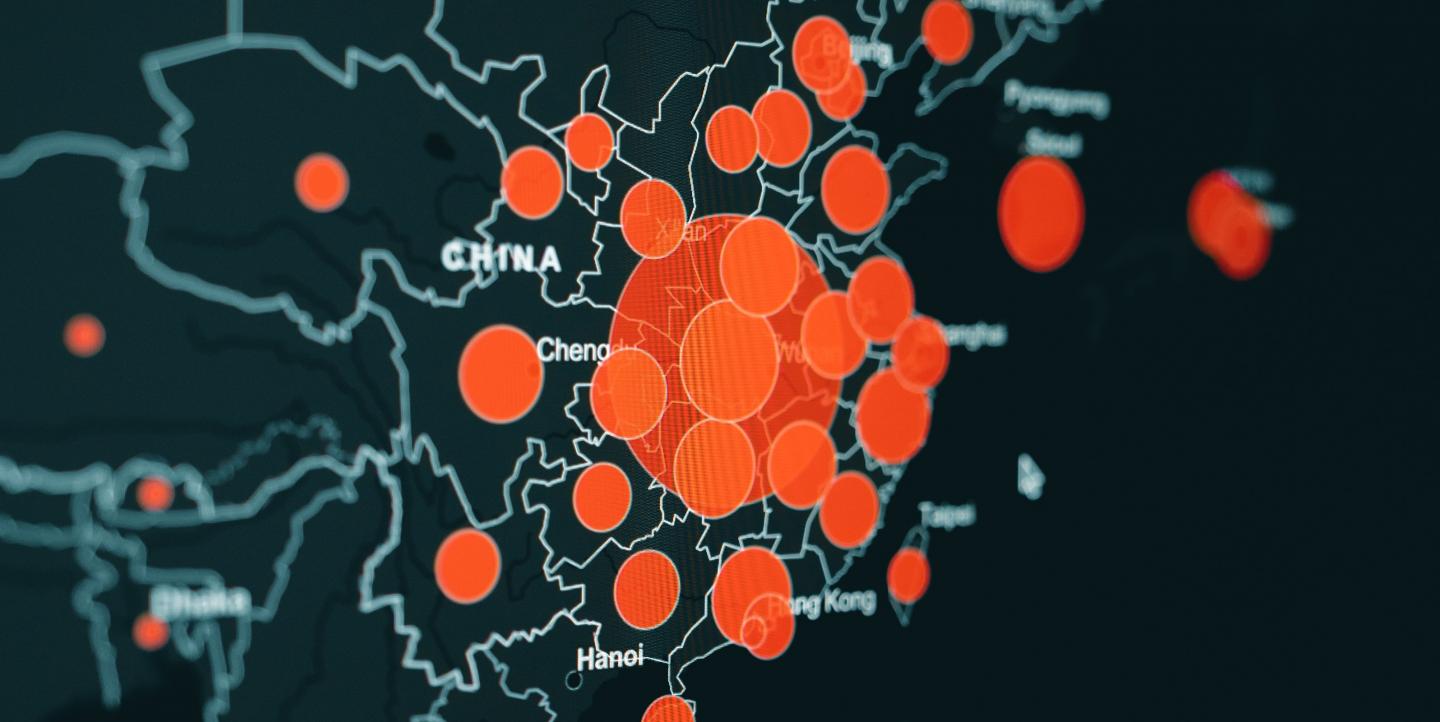

Reporting from China has long been a challenge, but with the country at the epicenter of a global pandemic, information control and censorship appear to be on the rise, South China Morning Post reporter Linda Lew said during an ICFJ webinar.

“I do feel that information control is getting stricter and stricter,” she said.

Lew has been covering the global health crisis since January, when she flew to Wuhan to cover the outbreak, then known only as “viral pneumonia.” After heading to a local hospital, she quickly drew the attention of a propaganda officer, who escorted her to a nearby police station. There, authorities forced Lew to delete her photos and notes from her phone, took down her personal information and warned her not to return to the hospital, she said.

“That was an illustration of how hard it is to get access to information and people,” Lew told ICFJ President Joyce Barnathan, who hosted the session, Lessons Learned Reporting on the Pandemic.

It’s extremely risky for Chinese sources to speak out, she said. “We've had a lot of activists and scholars in China called in for inquiries or holding people to account for the early mishandling of the coronavirus. And unfortunately, these activists and scholars have been detained.”

“We've also had a really worrying case where a group of volunteers who were only maintaining a GitHub database to preserve some of these sensitive reports. The volunteers behind that database were also detained,” she said. “So I think all of these events point to a really worrying trend that censorship is being stepped up.”

At the beginning of the pandemic, she said, even the World Health Organization was not challenging the limited data China was willing to share.

[Read more: Key quotes: At a critical time, reporters persist despite threats to press freedom]

Scientists are often afraid to speak with reporters, she said, especially on matters that could reveal mismanagement by the government. And with good reason. After a Shanghai lab isolated and sequenced the novel coronavirus’ genome to share with the world, the Chinese government shuttered the lab for “rectification,” she said. “We don't have any official explanation from the authorities, so we can't say for sure, but it does seem very likely that this may be linked.”

“This was so important because once this sequence was made available, scientists from all other countries can then study the sequence and make diagnostic tests based on the sequence so they could get testing underway in their own countries,” she said.

Despite the difficulties, she said some reporters on the mainland “have done a stunning job in uncovering what has happened behind the scenes of the coronavirus, [from] documenting health care professionals’ fight on the front line, to stories of patients and their families, how they dealt with tragedies.”

[Read more: COVID-19 and press freedom: A conversation with David Kaye and Courtney Radsch]

The public has also shown its hunger for this information. After the censors removed from the Chinese internet a story about outspoken Wuhan physician Ai Fen, Chinese readers translated the story into dozens of languages and then re-posted the “new” stories on the popular WeChat social media platform.

“It was like a relay race to try to make this one story live on on the Chinese Internet,” Lew said. “It was really inventive, and I think that's something that showed the government and the world that they are not going to let the censorship try to deprive them of trying to find out the truth.”

To overcome the lack of access, Lew works the phones and searches social media for tips, which she then does her best to verify the information. Verification isn’t easy. After seeing social mentions that the government had disbanded chat groups that had discussed an outbreak at a prison in northern China, she got in touch with knowledgeable people in the area who provided information on the situation. However, authorities would still not confirm the story, so she could only report all the details after the government later released the information.

In addition to refusing to confirm information, the government also denies facts. “It's very difficult to try to separate what the government may be saying is fake and what is actually misinformation online,” she said.

In this environment, journalism plays an important role, Lew said. “I think the principles of journalism are needed more than ever,” she said. “Any time I report on some of these new claims or some of these new scientific studies, I would have to talk to at least several scientists to basically get their take on this,” she said. “You need to verify, verify and verify.”

The Trump administration’s finger pointing at a Chinese lab could undermine efforts to hold China accountable for mishandling the COVID-19 outbreak, she said. “I don't see any merit in this claim at all. I understand why the U.S. is doing this, but I think they're going down the wrong road.”

While China did make mistakes,“these unfounded accusations really take away from legitimately holding the Chinese government to account,” she said. She said she has interviewed a number of U.S. and other scientists who have worked with the lab, the Wuhan Institute of Virology. “They think the accusations are completely without evidence, and they vouch for the safety of the Institute,” she said.

In the future, the situation is not likely to get easier, but she said she and her colleagues are working hard to uncover exactly what the Chinese government knew about the virus and where it originated.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Clay Banks.