This article is part of our online coverage of reporting on COVID-19. To see more resources, click here.

Despite years of suppression, investigative reporting has somehow managed to survive in China. But the COVID-19 outbreak has sparked a new wave of Chinese muckraking. In the few months since the pandemic began in the Chinese city of Wuhan, Chinese media appears to have produced more high-quality investigative reporting than it had done over the past several years.

This is partly due to a few external factors. A number of Chinese news organizations have made use of a short “window of opportunity” to produce and publish widely shared investigative reporting with the tacit consent of authorities. Chinese authorities use such “windows” to loosen their control over the news media while closely keeping track of public opinion in order to adjust their propaganda tactics. And unlike the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong last year — which concerned politics, one of the most sensitive topics in China — COVID-19 affects everyone, regardless of one’s politics. It’s often easier for people to reach a consensus on environmental and public health issues.

Yet above all, it is the extraordinary efforts of individual journalists that have created this sudden and vibrant revival of Chinese investigative reporting. Chinese journalists are working hard to produce stories supported by solid evidence, while at the same time circumventing censorship. While some stories were removed from the internet a few hours after being published, Chinese audiences — who can easily spot politically sensitive content after years of navigating official censorship — have a habit of archiving stories, republishing them on other platforms such as Notion and Evernote, and sharing them on social media, in a relay race against censorship.

[Read more: Do's and don'ts of reporting on COVID-19 — from a non-science background]

China’s best journalists found themselves plunged into an unexpected crisis, with an out-of-control, little understood infectious disease and a government prone to secrets. They have reported on COVID-19 as it has killed over 3,200 people in China, almost half the world total, with nearly all of those dying in the epicenter, Hubei Province. The journalists have worked amid extraordinary conditions: a virulent health threat, a lack of reliable data, widespread trauma, official censorship, and quarantines imposed on some 50 million Chinese.

As COVID-19 now spreads globally, what advice can Chinese journalists share with colleagues across the world from their experience? GIJN’s Chinese Editor Joey Qi interviewed several journalists who are on the frontlines of covering COVID-19. Nearly all asked to remain anonymous. Here is a summary of their tips for reporters worldwide:

Learn the Basic Laws and Regulations

If you are not a health reporter, make sure to acquaint yourself with the basic laws and regulations for infectious diseases, as well as prevention and control procedures, before you go out to report. For example, what are the diagnostic criteria for COVID-19? What are the procedures for disease reporting? What are the disease control methods? Going through this information will help you understand the system of infectious disease prevention and treatment. You’ll find this to be helpful throughout your reporting.

Scrutinize Policies

When every newsroom is covering COVID-19, it is important to come up with fresh story angles. Wu Jing, a reporter for Health Insight, an online publication focusing on the healthcare industry, says journalists can often find stories by examining policies for prevention and control of the disease. “For example, after Wuhan was placed under a lockdown policy, you need to think about what kind of problems Wuhan residents might encounter,” she said. “Will there be any shuttle services provided for patients who need to go to the hospital? When making triage policies, has the local government taken this into consideration?” By scrutinizing such policies you will be able to uncover unreported stories.

[Want to better serve your readers regarding COVID-19? Read these tips.]

Don’t Ignore Small Hospitals

When a new virus emerges, it is essential to ask two questions: What is this new virus, and where does it come from? Chinese scientists quickly found the answer to the first question, but the second remains a partial mystery until today. Huanan Seafood Market, a wet market in Wuhan, is currently identified as the place where the outbreak of COVID-19 started. Wu Jing of Health Insight says that while journalists often focus on major hospitals, small hospitals near this wet market should not be ignored, as they may be where you’ll find the most important leads.

In general, Wu said, rather than only focusing on large or specialized hospitals, or medical experts deployed by the government to tackle the disease, pay attention to small health facilities. Patients often visit them first before seeking treatment at a major hospital. “This is because people infected with the coronavirus usually show symptoms such as a cough or fever at an early stage — they are more likely to visit a nearby health center or a regional hospital, rather than a tertiary hospital or those specialized in infectious diseases,” she said. “Not to mention how long you have to queue up at general hospitals to get registered.”

Locate Yourself in the Community

Several Chinese reporters said that informal interviews with doctors, volunteers, and residents helped them with their reporting, enabling them to discover unexpected stories and interviewees.

It is therefore important to base yourself at a good location with accessible transport where you will be likely to meet people in the affected communities. Wu stays at a hotel that is near two different hospitals designated to treat COVID-19 patients and not far from the wet market. This makes it easier to carry out casual interviews with people in the area, Wu said, as well as to bump into doctors who have also been put up in hotels.

Look for Sources on Social Media

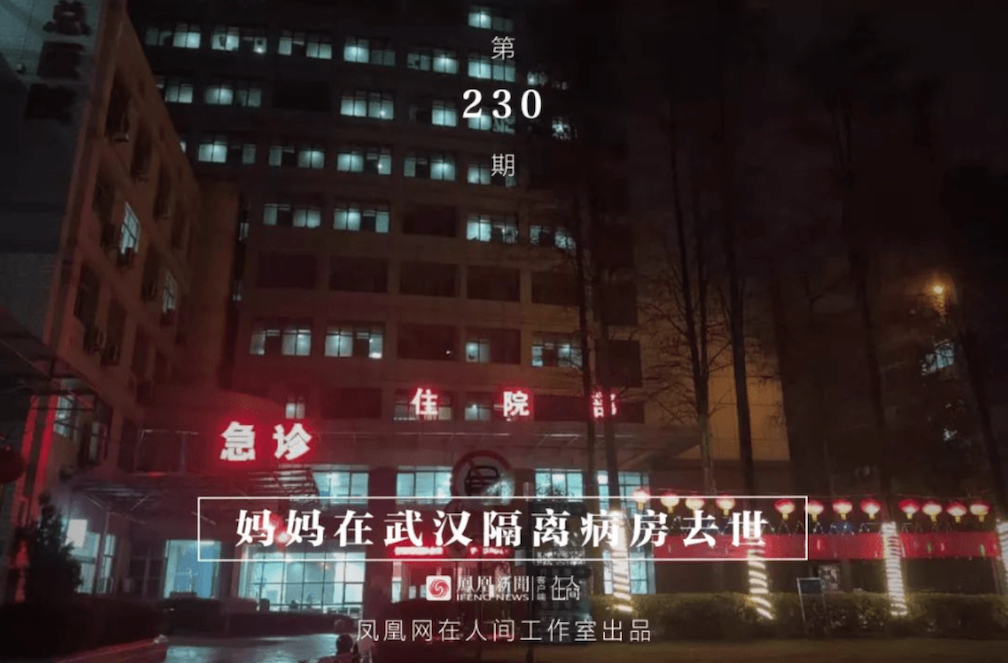

When COVID-19 broke out, there was a temporary shortage of medical resources and many patients hoping to get tested for the disease asked for help on social media, mostly on China’s Twitter-like platform Sina Weibo and social networking app WeChat. Some of the most widely read stories of the outbreak were discovered by journalists following these posts, such as Mother Passed Away in the Quarantine Ward, which was published by the Chinese site NetEase. Many people are also contacting news organizations directly with stories by messaging their official WeChat platforms.

Show Kindness, Build Trust, and Know When to Let Go

People are suffering from a lot of stress because of the disease. It is important to be kind to those who are willing to be interviewed, by showing empathy, offering protective supplies like surgical masks or alcohol for disinfection, and helping them contact aid organizations if needed. “In a word, provide what they need most at the moment as much as you can,” Wu said. Showing kindness lays the foundation for mutual trust and good reporting, by helping people to open up.

Be accepting when people decline to be interviewed or respond to your messages. Learn to let go. Says Wu: “You have to constantly remind yourself of the possibility of being turned down for any one of the interview requests.”

Work Closely with Your Editor

Producing a strong investigation or series depends as much on planning and collaboration with your editor back in the newsroom as it does on the critical work of the reporter on the front lines. As the reporter at the scene, spending so much time doing interviews and finding stories makes it easy to lose track of changes in public opinion or audience interests. This is when your editor can provide vital advice on where the story should go.

Editors should be able to look at the situation from a broader perspective. When working on a big project, they hand out assignments to reporters and organize the reporting for publication. On top of this, newsroom staff should provide practical and emotional support to reporters on the ground.

Provide Clear Explanations

Covering infectious diseases requires reporters to have some specialized knowledge in health and medicine. As well as providing information and evidence-based journalism, reporters need to be able to explain or translate scientific terms or other information for the public. Only then can the public get a better understanding of the entire situation.

Take Care of Yourself Emotionally

Covering a pandemic and keeping up with all the relevant news everyday can be a traumatic experience for journalists. You need to take care of yourself emotionally. A few of the reporters covering COVID-19 in Wuhan shared these tips on how they do self-care:

- Never shut yourself away in a room all day. Make sure to see and speak with your friends.

- Pick a hotel room with good lighting and a window with a view because your physical environment can have a significant impact on your emotions.

- Do not let yourself drown in disease-related news. Distract yourself by reading or watching unrelated content.

- It’s alright to cry when you are feeling stressed. Crying is a good way to release your emotions.

- Maintaining physical health can help when dealing with negative emotions. Try meditation, yoga, or other forms of exercise to help you stay healthy and well.

This article was originally published by the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN). It was republished on IJNet with permission.

Joey Qi is the editor of GIJN in Chinese. He has over seven years experience in journalism, including three years in media management. He is one of the founding members of The Initium Media, where he designed the daily news section and built the reporting team.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Dimitri Karastelev.