The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

France>U.K.>U.S.……at least when it comes to not sharing junk news, according to a memo from Oxford University’s Internet Institute’s Project on Computational Propaganda. The researchers measured “bot activity and junk news” on Twitter in the final week of campaigning before the U.K. general election (from May 27–June 2) and found that junk news (defined as “misleading, deceptive or incorrect information purporting to be real news about politics, economics or culture”) made up 11.4 percent of content shared…

compared to 12.6% during the first U.K. sampling period, 12.5% in Germany and 5.1% and 7.6% respectively in the two election rounds in France. We also found that U.K. users were not sharing as much junk news in their political conversations as U.S. users in the lead up to the 2016 elections, where the level of junk news shared was significantly higher. In the days leading up to the U.S. election, we did a close study of junk news consumption among Michigan voters [previously covered in this column] and found users were sharing as much junk news as professional news content at around 33% of total content each.

Substantive differences between the qualities of political conversations are evident in other ways. In the U.S. sample, 33.5% of relevant links being shared led to professional news content. In Germany this was 55.3%, and in France this was between 49.4% and 57% of relevant links across both election rounds. Similarly, in the current U.K.-based study we show that 53.6% of relevant links being shared led to professional news content.

So, um, maybe these European countries are learning from Americans’ mistakes? Adding insult to injury for those of us on this side of the Atlantic, “we are also able to show that individuals discussing politics over social media in the European countries sampled tend to share more high quality information sources than U.S. users,” the researchers write.

“Social contexts may impede fact-checking” Poor old fact-checking, there’s never any good news about it. Pacific Standard’s Tom Jacobs writes up a recent paper from researchers at Princeton, “Perceived social presence reduces fact-checking.” From the paper:

Eight experiments suggest that people are less likely to verify statements when they perceive the presence of others, even absent direct social interaction or feedback. The notion of perceived social presence draws from the literature on Social Impact Theory and social facilitation which has examined the influence of noninteractive others — whose “mere presence” may be real, implied, or otherwise imagined — on individual behavior.

Why is this? It doesn’t seem to be “diffusion of responsibility” or “social loafing” (i.e. everyone’s waiting for someone else to call it out: In one experiment, people were actually paid for each statement they fact checked, and still “participants flagged, or fact-checked, fewer statements in the group compared to the alone condition.” The researchers also didn’t find “a consistent effect of social presence on the number of statements identified as true.” But:

Our data provide some evidence for the third route—reduced vigilance—and suggest that social contexts may impede fact-checking by, at least in part, lowering people’s guards in an almost instinctual fashion. These contexts can take the form of platforms that are inherently social (e.g., Facebook) or can be cued by features of online environments such as “likes” or “shares” that a message receives.

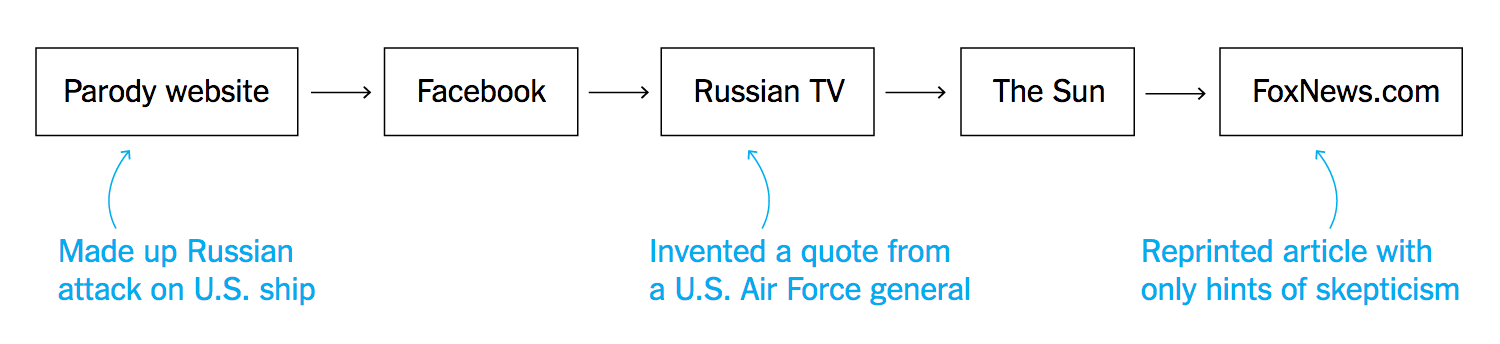

From “the shadowy reaches of the internet” to FoxNews.com. The New York Times’ Neil MacFarquhar and Andrew Rossback tracked how a fake story about a Russian attack on a U.S. ship spread from a Russian “opinion piece, apparently meant to be satirical” to FoxNews.com. The original fake piece was written in 2014 and traveled to Facebook, Russian TV, British tabloids The Sun and The Daily Star, and finally to FoxNews.com (it was taken down after the Times ran this story).

This article first appeared on Nieman Lab and is republished with permission.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via Live4Soccer(L4S).