The clip is heartbreaking. A CNN reporter is interviewing an obviously distraught woman who had just reached safety from Hurricane Harvey, and then the woman broke down and yelled at the reporter: “Y’all try to interview people during their worst times. That’s not the smartest thing to do. People are really breaking down and y’all sitting here with a camera and microphones trying to ask us what the f--- is wrong with us.”

It’s 13 days later now, and a bigger, more dangerous hurricane is in the news. But before journalists cover the eventual victims of Hurricane Irma, they should reflect on that Hurricane Harvey moment.

In his essential Reliable Sources newsletter, CNN’s Brian Stelter noted that the reporter had asked the woman if she would go on camera, and the woman had said yes. He added, “The exhaustion and the emotion in her voice conveyed just how dire the situation has become for some Houstonians.”

The clip does more than that. It makes a strong case that journalists need to rethink how they engage with the communities they cover, especially during times of trauma.

Because while this is relevant in the short term, for Hurricane Irma, it’s also relevant in the long term, as journalists work to regain public trust. And because this is not an isolated incident.

Every one of the 19 Oregon-area reporters who covered a 2015 mass shooting at Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon, and participated in the Reporting Roseburg project told a colleague and me that they felt a calling to bear witness to the tragedy, to make sure the victims weren’t forgotten, to honor the citizens and heroes who helped in the aftermath.

But the Roseburg community didn’t see that. A UCC student, speaking at a town hall organized by Oregon Public Broadcasting a month after the shooting, spoke for many when she said, “There was honestly a lot of harassment from the media for us to tell our stories. … It was rude, honestly. It wasn’t polite. Honestly, the media was probably the second trauma, almost, for us.”

There’s a disconnect there, and it’s an important one: These reporters, like the CNN reporter, were not doing anything unusual. They were deploying the basic reporting skills they’ve been using since j-school—or that they were taught on the job.

So what does it say about journalism’s fundamental information gathering processes that when they are tested in a high-visibility, high-importance situation, they can cause harm?

As we all know, public trust in the U.S. media is at an all-time low.

The conversation around this distrust tends to focus on the big picture. “Fake news.” Political views. Media literacy. They’re real problems, and difficult ones, but the narrative is actually convenient: It puts the onus on the public to better understand journalism. Fixing this narrative requires nothing of journalists.

With historic levels of distrust in media, that’s not OK. Journalists and journalism educators need to examine their own practice.

That’s harder work. It’s messy. And we might not like what we find.

Julia Dahl wrote recently about an interview with a sex offender and his father that she has been thinking about differently. At the time, she knew it had ruined their day.

“What didn’t occur to me until years later,” she wrote, “was how that interaction may have shaped the way they thought about reporters, and the entire news media, for the rest of their lives. Ten years later, when their president told them that journalists were ‘enemies of the American people,’ and ‘mainstream media’ was pumping out ‘fake news,’ might my daylight notebook-and-camera ambush have made it more likely they’d nod their heads and say, Hell, yeah?”

Re-examining what most of us call “basic values” but what educational psychologist Edgar Schein purposely calls “basic underlying assumptions” is a monumental undertaking. In his 2010 book "Organizational Culture and Leadership," Schein writes, “These tend to be taken for granted by group members and are treated as non-negotiable. Values are open to discussion, and people can agree to disagree about them. Basic assumptions are so taken for granted that someone who does not hold them is viewed as a foreigner or as ‘crazy’ and is automatically dismissed.”

Always interview witnesses to find out what happened. Always use names of those charged with a crime. Always interview victims of a disaster to make the consequences more real.

These are basic underlying assumptions of journalism, and I don’t hear too many serious discussions about whether we should always do those things. (An exception: No Notoriety has pushed an important discussion about naming the perpetrators of mass shootings.)

Journalism needs those discussions. Yes, journalists need to seek truth, and that means they need to ask questions during difficult times. That’s a moral imperative. But so is minimizing harm, and that is something that can be particularly difficult in the moment, on deadline, as news is breaking. That’s why I’m asking my students to discuss these issues now, in the classroom, where they have time to reflect.

Many of the journalists in the Reporting Roseburg project said they were cautious in approaching sources because, as one put it, “For me, it’s hard to even envision that I would want to speak with someone at a time like that.”

Yet none of the journalists questioned the idea that journalists must immediately interview victims and witnesses. If journalists wouldn’t want to answer their own questions, why are we asking them?

Lori Shontz is a journalism instructor at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication.

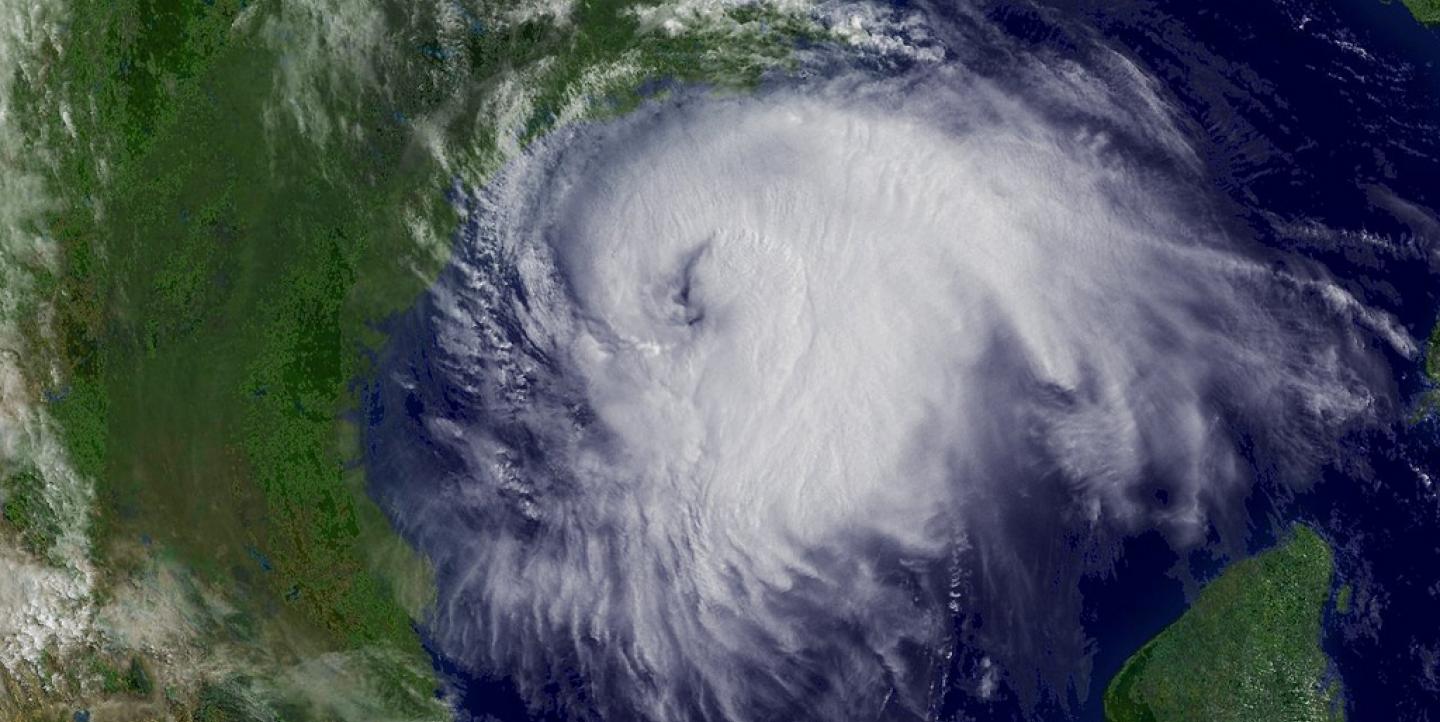

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via NOAA Photo Library.