As umbrellas opened in the streets of Hong Kong, one app was massively downloaded by protesters: FireChat. Engineered by OpenGarden, it allows people to chat on a public thread, even without an Internet connection.

Imagine a mix between WhatsApp and Twitter, with a possibility to access it offline if you are in the same place as other users. We wanted to know more about the app, so we video chatted with Micha Benoliel, CEO of OpenGarden, from Hong Kong.

What is FireChat?

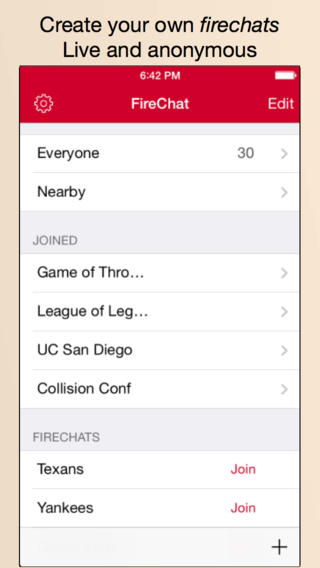

FireChat is a messaging app that enables you to communicate even when you don't have Internet access through your cellular data connection or if you are not connected to WiFi. When you are connected to the Internet, you can create big group of discussions and broadcast a lot of information to a large number of people, and when you are not connected, you can keep on broadcasting content and receiving messages through a technology called 'peer-to-peer mesh.' Your smartphone has a radio to connect you to a cell tower or a WiFi network, but it also has radios to connect you to other phones directly. FireChat creates 'daisy channel platforms' and your messages can flow from one phone to another. The range is about 250 feet [about 76 meters].

How do people use it in Hong Kong?

You can have thousands of people who are notified about practical information. On Sunday [October 5, 2014], there were so many people, the mobile cellular networks were all inaccessible: nobody could use messaging apps or connect to the Internet. But FireChat was working: I took screenshots of what was happening on the app, and people were using it to explain where the streets were blocked, where people needed some help, what kind of logistical elements were missing, like water, umbrellas, etc. If the police showed up, people could inform others. You have real-time interactivity with the chat application; that is what is really powerful.

Did you expect this much success?

When we launched the application in March 2014, it was a demo app, and it was already a success. Ten days after the launch, we were no. 1 in 15 countries and in the top 10 in 115 countries among social networking apps. It is half surprising what is happening in Hong Kong: We saw people using the application in the same context during the student protest in Taiwan, the 'Sunflower Movement' [in March-April 2014]. The government threatened to shut down the Internet, so the students installed the app to keep on communicating with protesters that were inside and outside the Parliament. In Hong Kong, half a million people created a FireChat account, a huge number for a city with a population of 7 million people. It was a complete surprise because we did not expect it would take such a big proportion. On Sunday, it was 25 times bigger than anything we have ever experienced in the past. Also, we saw people around the globe creating chatrooms to support what is happening in Hong Kong. We had a spike of installs in the U.S., Australia, Europe and even in China.

How about privacy for the users?

It is like other social networks: you can decide to reveal your real name or you can use an alias and remain anonymous if you wish. Everything is public: everything you say can be seen by anyone, and that is why it is so powerful. You don't need to actually know the people to broadcast information. We have been working to create verified accounts, and we accelerated the work on this. Due to the events in Hong Kong, we realized a lot of people were posting a lot of information, and [with] the feedback we got from some of the students, it made sense that we should verify some of the users who post a lot of content to make sure they are a trustworthy source of information.

Are you talking to the media industry about applications for journalists?

The first people we are contacting to get a verified account are journalists. Patrick Boehler, reporter at the South China Morning Post, is one of them for example. Also, journalists can observe and participate in the chats. But as students need support and reliable information and given the volume of messages in the chatrooms, it is important to keep the communication channels open. It could be counter-productive if many journalists from around the world were suddenly asking a lot of questions. So we make sure that the first people who are verified genuinely care about Hong Kong.

This post originally appeared on the Global Editors Network website and is republished on IJNet with permission. The Global Editors Network is a cross-platform community committed to sustainable, high-quality journalism, empowering newsrooms through a variety of programs designed to inspire, connect and share.

Laure Nouraout is the social media manager for the Global Editors Network. Follow her on Twitter: @LaureNouraout.

Image CC-licensed on Flickr via hurtingbombz. Secondary image courtesy of Open Garden's FireChat.