When covering elections and campaigns, online publications rush to publish fact-checking articles that analyze candidates’ most popular statements. But that’s the problem - these are just articles and not engaging platforms.

To develop an appealing platform that fact-checks and informs the public while engaging politicians, journalism organizations might want check out Agência Pública’s Truco for inspiration.

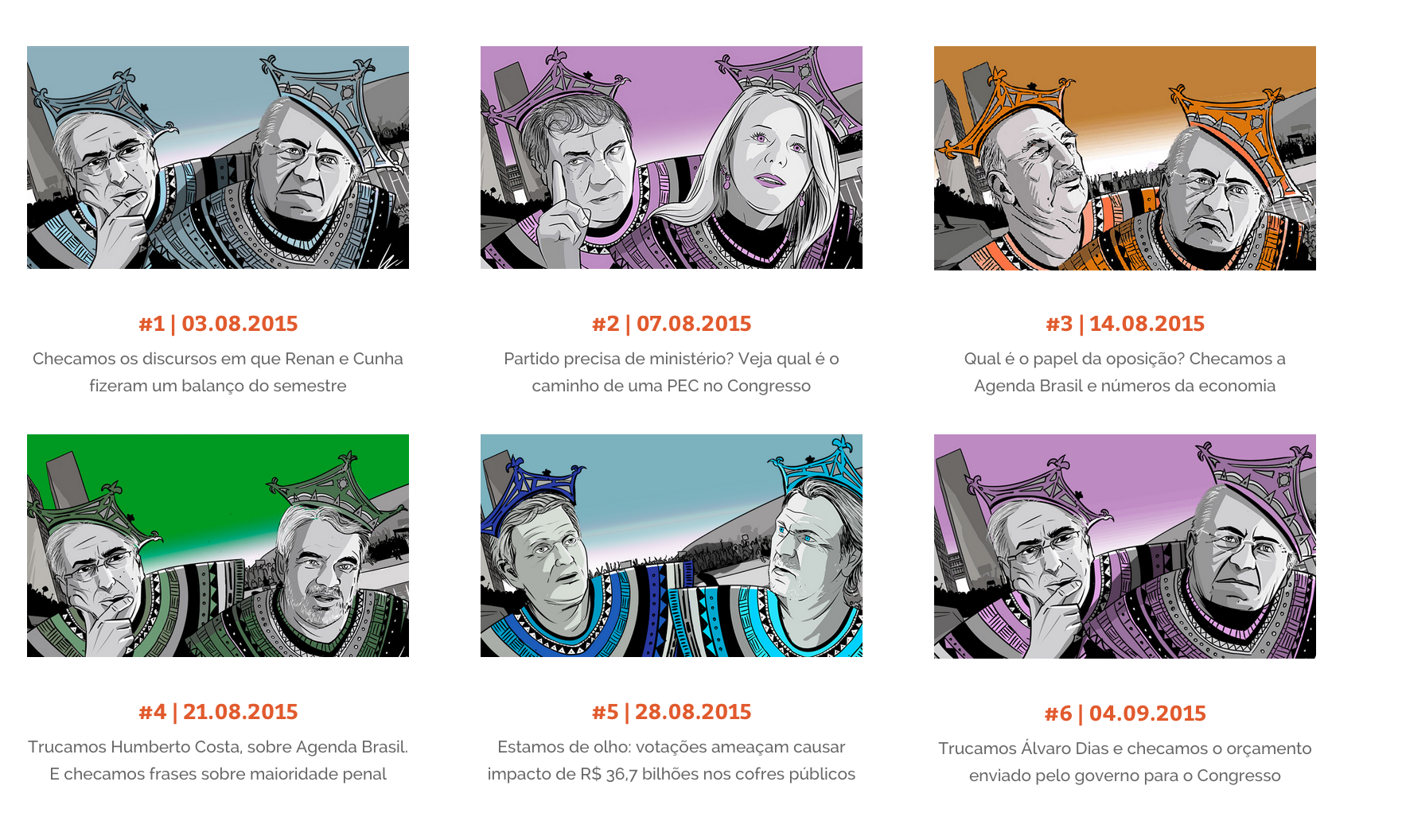

Agência Pública, a nonprofit investigative journalism organization in Brazil known for in-depth reporting, eye-appealing graphics and online engagement, launched fact-checking platform Truco during Brazil’s 2014 presidential elections, and this August the publication launched Truco No Congresso to focus on Brazil’s senate and congress.

The word Truco comes from a South American card game of the same name. Each player has three cards and the person that claims to have the highest card wins each trick. To double the stakes, a player can call Truco, and if the opponents accept it, they must show their cards. The Agência Pública team chose this name because for them a Truco is a challenge to politicians to show their cards. So when the team makes a Truco, it not only fact-checks what politicians say, but also challenges politicians to add more information or clarify statements.

"What we want is for people to tell the truth,” said Natália Viana, a director of Agência Pública. “We want people to bring in more documents and more information.”

The Âgencia Pública team realized early on that within Brazilian culture, nothing is as straightforward as just saying it’s true or not - there are different levels of truth. Thus, the team designed playing cards illustrated with colorful and vibrant designs that correspond to the level of truth in a statement. A Blefe, the lowest level, means that a statement is completely false. Que medo includes statements that would have a negative impact on human rights.

Não é Bem Assim means the information was exaggerated. Candidato em Crise! means that the candidate said something that contradicts an earlier statement. Tá Certo, Mas Peraí means that the information was correct but it wasn’t contextualized when it was presented. A Zap means that the statement was true and relevant.

“We decided early on that we didn’t want to congratulate politicians for telling the truth,” Viana said. “That is what they should always be doing."

The project ran everyday for three weeks leading up to the general presidential elections Oct. 5 and for two weeks leading up to the run-off between Aécio Neves and Dilma Roussef Oct. 26. During that time, 129 cards were distributed and 18 Trucos were made.

Truco’s impact was evident during last year’s campaign. Brazilian presidential candidate Aécio Neves claimed that he had an approval rating of more than 90 percent in Minas Gerais, the state that he governed for more than seven years. When Agência Pública checked this statement, the publication found that Neves had exaggerated the facts and declared his statement as Não é Bem Assim. From then on, media organizations stopped reporting this statistic every time they talked about Neves, Viana said.

A political and economic crisis is mounting in Brazil right now, so Truco no Congresso is focusing on an area of government that garners the most media attention everyday. Each day editor Maurício Moraes scans the congressional transcripts looking for two types of phrases - those that need more in-depth information for the public and those that include questionable data. Once Moraes chooses the phrases, he passes them on to the fact-checking team, which also includes members of the publication Congresso em Foco. With that information, Moraes edits and produces a weekly Truco report.

Moraes has found Congress to be a more difficult task to fact check than presidential candidates. Presidential candidates are trying to show off their accomplishments so tend to use facts to back up their statements, he said. Congress members don’t have to show off because they are already elected. So many of their statements are very subjective.

“There is less data and conversation tends to be more of a political conflict between government and the opposition, so it takes more work to find phrases to check,” Moraes said. "There is a lot of material, but it is less evident."

Perhaps that most unique element of Truco is the engagement of politicians. Agência Pública recently called Truco on Brazilian politician José Guimarães, who asked if it was reasonable for government ministers to vote against a government that is led by their own political party. Guimarães responded to Agência Pública’s questions within a week.

Images courtesy of Agência Pública