It all started with a recurring question in our newsroom: Why are so many older adults removed from the Pensión 65 social program without explanation? To understand this, we investigated the system that determines which households are considered poor in Peru: SISFOH. This system cross-checks administrative records with data collected in the field to estimate a household’s poverty level through an algorithm. But when information is incomplete or misinterpreted, it can exclude the very people who most need support.

Even though this isn’t artificial intelligence in its most advanced form, it is an automated system — and one with serious limitations. It often fails to identify extreme poverty in urban areas, overlooks the isolation and vulnerability of old age, and can deepen inequalities if it isn’t adjusted with fairness and context in mind.

None of us — except for Jason Martínez, our data scientist — had previously investigated an algorithm behind a social policy. We learned by doing: filing public information requests, interviewing experts, reviewing regulations, and reporting from the field. That’s how Invisibles was born: an investigation that combines technical analysis, human stories, and public service journalism.

Why this issue?

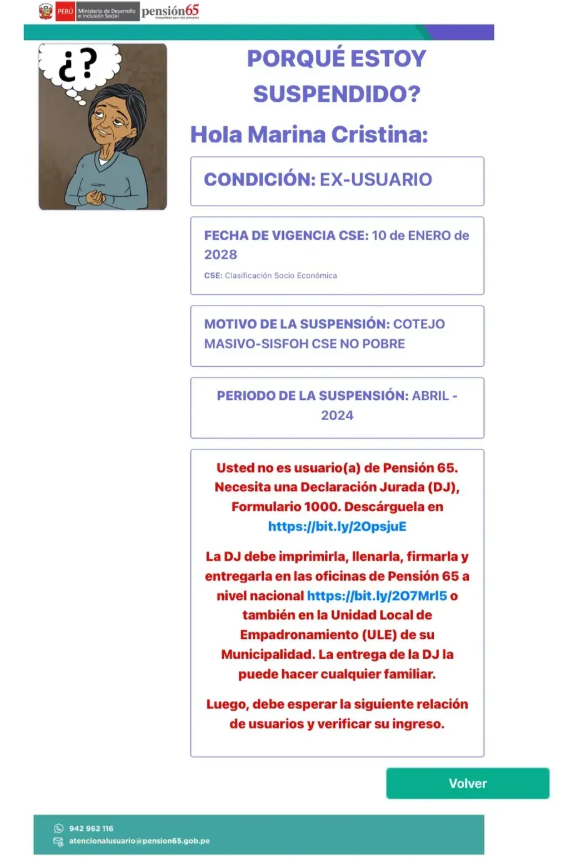

Over the past few years, more and more older adults in Peru have shown up at the bank only to find out — without warning — that their pension payments had stopped. “There’s no deposit. Check your status,” they were told. No one called. No one explained. They had simply been erased from the system.

We investigated and confirmed that many of these exclusions were not due to real improvements in people’s living conditions, but to structural flaws in SISFOH. This system, developed with support from the World Bank, uses a model called Proxy Means Test, which estimates poverty based on indirect data like housing, utilities, or household assets. But in Peru, especially in urban settings, the model fails to capture abandonment, dependency, or fragile family networks in which many older adults live.

The algorithm evaluates poverty at the household level. If an older person lives with relatives who have some income or assets, the system assumes they don’t need support—even if, in reality, they are neglected, without care, or left with no resources. On paper, they are not classified as extremely poor. But in real life, they are.

Our hypothesis

Peru’s poverty classification system has prioritized avoiding inclusion errors — granting benefits to those who don’t need them — but at the cost of making thousands of exclusion errors: leaving out those who do need help. This has worsened since the pandemic, which drastically changed living conditions, especially in urban areas. Yet the system has not been updated accordingly.

What we did

The core Invisibles team included three journalists from Salud con lupa: Fabiola Torres, Jason Martínez, and Rocío Romero. We worked with Ro Oré (illustration), Álvaro Cáceres (video), and Max Cabello (photography). From the start, we defined two goals: to conduct a rigorous investigation of the SISFOH algorithm and to create public service content for those affected.

Our methodology included:

Sixteen public information requests to access national datasets on Pensión 65 beneficiaries, those excluded, reinstated, and on the waitlist (2020–2025).

Interviews with experts such as Carolina Trivelli, Lorena Alcázar, and Angelo Cozzubo, who explained the system’s technical and operational limitations.

Review of regulations and academic studies, including key research by Jonathan Clausen (PUCP), who proposes a multidimensional poverty index for older adults.

Field documentation of real cases in Lima, Arequipa, and Ucayali, showing how a flawed classification can cut off an older person’s only source of income, affecting their nutrition, health, and access to care.

Verification of cases where people were wrongly excluded and only reinstated after confusing, drawn-out appeals. In some cases, the government had even wrongly declared them dead, as flagged by the national audit office.

Confidential conversations with SISFOH officials who raised concerns about data quality and local-level implementation. Untrained data collectors often make errors in interviews, which are then fed into the algorithm.

What we found

Between 2020 and June 2025, over 81,000 older adults were excluded from Pensión 65 and later reinstated — many after long and frustrating appeals. This shows they should never have been removed in the first place.

We found failures on three levels:

The algorithm and the household survey don’t detect urban extreme poverty, elderly abandonment, or contextualize electricity use (e.g., during pandemic lockdowns).

Local Data Collection Units (ULEs) often lack trained staff and resources, leading to inaccurate or inconsistent records.

The appeals process is slow, unclear, and inaccessible — especially for older adults who are alone, ill, or have no support.

We also found that 171,000 people are currently on the waitlist for Pensión 65, even though they meet all eligibility criteria. The reason? There is no budget to include them.

What impact are we seeking?

We released Invisibles at a key moment. Peru now has a law (Law No. 31814) promoting the use of artificial intelligence in public policy, and the World Bank has approved a $55 million loan to modernize SISFOH.

In this context, we aim to:

Make a structural problem visible: show how automated systems can unfairly exclude vulnerable people if the data is poor and the algorithm doesn’t read urban poverty well.

Fill an information gap: create practical guides to help older adults understand what happened with their pension and how to appeal.

Open a rights-based conversation about algorithms: share this investigation through media, public forums, and training spaces — because journalism can also help drive policy change.

We believe technology can improve social policy — but only when it’s applied with quality data, contextual awareness, and accountability. A system that decides who deserves help without fully understanding people’s lives is not just inefficient. It’s profoundly unjust.

We thank the AI Accountability Network of the Pulitzer Center for supporting this work.

Fabiola Torres is a former ICFJ Knight fellow.

Main image by Max Cabello/Salud con lupa. Peru.

This is article was originally published by the Pulitzer Center and is republished on IJNet with permission. The original methodology and story series were published by Salud con lupa.