Jane Lytvynenko and a colleague at BuzzFeed News got into the habit of practicing with one new open source tool every week during slow news periods. As she says, it was this habit that enabled the team to reveal that the US Capitol riot on January 6 had been planned by far right groups for weeks — just hours after the event.

In a GIJN webinar titled “Investigating the Radical Right: A Global Perspective,” a panel of four veteran journalists with experience in digging into extremist hate groups shared tips and practical insights on how to track their activities.

Their discussion follows an upsurge in the radical right around the world, as witnessed by phenomena like the rise of violent ultranationalist groups in Ukraine, the US Capitol insurrection, violence against religious minorities in India, and cross-border cooperation between far right gangs in various nations. Lytvynenko was joined on the panel by Vinod K. Jose, executive editor of India-based narrative journalism magazine The Caravan; Michael Colborne, a contributor to investigative nonprofit Bellingcat who focuses on far right groups in central and eastern Europe; and Will Carless, who covers extremism for USA Today.

While presenting a serious threat both to democracy and the media, the panelists agreed that the good news for investigative reporters is that far right extremists “really aren’t that smart” about covering their digital tracks. The bad news: coverage can unwittingly amplify their message, reporters are at risk of harassment or violence, and official data on these groups is generally so poor that reporters need to become their own experts.

“It’s actually quite easy to investigate the far right online, because they’re not very sophisticated actors,” said Lytvynenko. “For instance, you can use tools to find Telegram channels that these groups consider hidden, but are not. What’s [surprising] is how willing people are to use their real names.”

“These groups really span the globe, ranging from white supremacists and neo-fascist gangs to religious fundamentalists, even to so-called fascist drinking clubs and fight clubs,” observed Carless, who also served as moderator. “And these are growing — digitally, ideologically, financially — but their networks are poorly understood, and investigative journalism in this area has really lagged behind.”

[Read more: 6 must-know hacks for investigative journalists]

Carless’s tips include:

- You need to be the expert. “Be very careful relying even on established sources for defining the groups and individuals you’re tracking,” he said. “A lot of the information out there about these people is simply wrong. The only way you can truly understand extremist groups is by knowing them well enough to create your own definition of what they stand for, and how far they will go to accomplish their goals.” One valuable source he did point to: The International Network for Hate Studies.

- Be deliberate about your digital safety. Given the heightened risk of harassment and doxxing (the malicious publication of information such as home addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses) from far right groups, it’s important to actively follow digital hygiene protocols, like those listed on Carless’s Digital Safety tipsheet.

- Don’t be scared off by critics. “I primarily cover the far right, but I can honestly say that most of the abuse I get is from the far left — harangued on Twitter for interviewing extremists; decried for suggesting that even terrorists are human beings,” said Carless. “Our ability to accurately and fairly pass on information to our audiences becomes cramped the moment we give in to any one political pressure group that seeks to ridicule or minimize us. And that will happen.”

Far Right by GIJN

The Caravan’s Jose neatly summed up the characteristics that unite the seemingly disparate right wing groups around the world: “In a nutshell, the far right hates democracy. They are hostile to diversity and consensus. They often have civilizational goals, rather than temporary political goals.”

The magazine has covered, in-depth, the rise and violent impact of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the nation’s most powerful Hindu-nationalist organization.

“It’s probably one of the most difficult beats to cover in terms of safety,” said Jose. “I lost an editor friend of mine a few years ago, and within Caravan there was a woman colleague who was harassed, and two other colleagues attacked. When the far right is in power, it multiplies the forces.”

[Read more: Tips for covering anti-democratic extremism in the U.S.]

Jose’s tips include:

- Follow the web beyond the organization. Jose noted that RSS has at least 60 affiliated organizations, as well as links to far right groups in eastern Europe and the US.

- Archive legal documents and personal papers. “This will help later, for legal defense if nothing else,” Jose remarked.

- Don’t forget the history of the group. “It might sound like an academic exercise, but it is necessary to understand the histories and the context of these groups to gain an idea of their long-term goals,” he said.

While disinformation is used by all ideological groups, BuzzFeed’s Lytvynenko said it had been “weaponized” by right wing groups.

“Disinformation is used to recruit and radicalize across the globe,” she said. “Spaces where disinformation spreads are often the same spaces where planning and recruitment takes place — often semi-private spaces like Facebook groups or Telegram chats. The reason we look at disinformation as a part of far-right groups is because of information laundering. Narratives become justification for violent action.”

Lytvynenko said her team uses any open source tools that work, even if they are designed for industries like marketing or security.

“That allows you to not only debunk false information, but also to map out how the information was spreading, where it may have originated, who may be behind it, and what else that group could be doing,” she said.

Lytvynenko said her top tools for far right digging include:

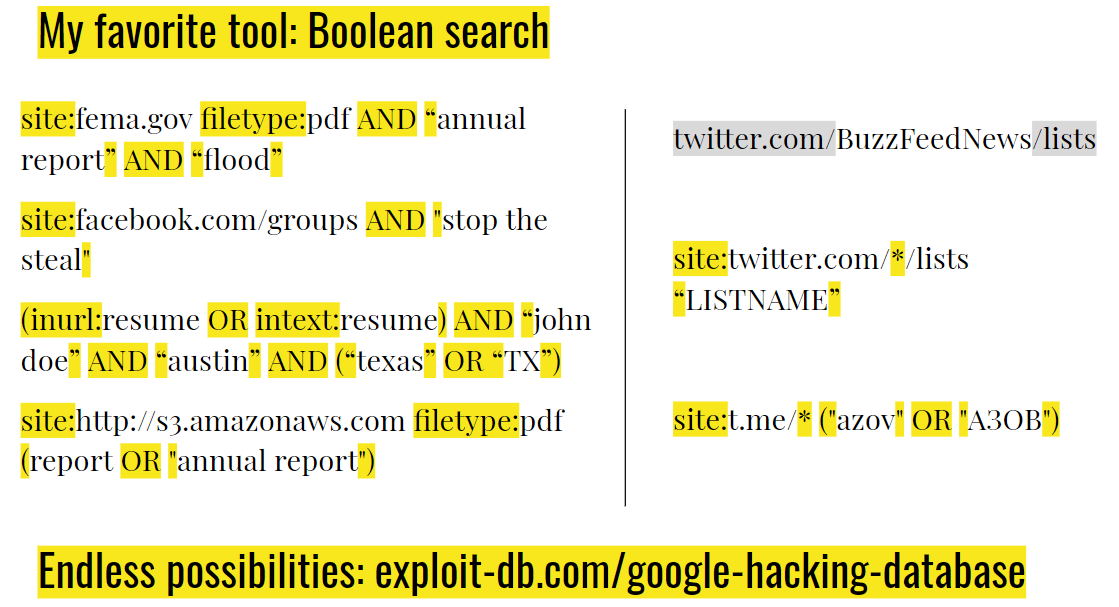

- Boolean search (word and symbol modifiers to sharpen online search). “My favorite tool is using search operators within search engines to zero in on the type of information you need, whether it’s government reports, contact information on your targets, or Facebook groups which are difficult to search via the platform itself,” she said.

- Interrogate Telegram. “Site:t.me with the asterisk wildcard (Site:t.me/*) is a great way to search Telegram, which is where the large chunk of far right activity is located,” she said. “For instance, you can find a lot of channels related to Azov, one of the far right movements in Ukraine, that you couldn’t find with other tools. If you use this to search for the Three Percenters — a far right group in the US — you’ll get some really interesting insight into how they vet new members, and where those members go from there.” Earlier, Lytvynenko told GIJN that tgstat.ru was another useful tool for tracking Telegram channels.

- Go Back In Time Chrome extension. “This and the Wayback Machine extension are my all-time favorites, because they allow you to, with two clicks, look for removed content,” she said. “You can search caches of the pages you’re on. A lot of people we look at remove content ex post facto.”

- OSINTCurio.us. “I check in with OSINTCurio.us almost every week — it frequently publishes tutorials on how to conduct online investigations; new ways for tackling the same problems,” she said.

Now focusing on transnational right wing extremism, and on militias in Ukraine, Bellingcat contributor Colborne said one effective strategy is to search for differences between group propaganda and private messaging, and in organizational support for individual members over time.

“The starting point is to look at the official output of their official social media channels, and to also get a sense of what the rank and file members think,” said Colborne. “I try to pierce through the distinction of the front stage — the way a far right group wants to present itself to the public through its social media channels — versus the backstage: what they don’t want publicly known.”

“The key with a movement like Azov in Ukraine is where individuals almost seem to fall out of favor with the leadership, and their stuff suddenly isn’t being re-posted, Colborne added. “What’s useful for me with open source is to understand changes in the subgroups associated with a far right movement.”

Colborne’s tips include:

- Browse Instagram profiles. “I especially use Instagram, in terms of trying to get a sense of what individual members or adherents in a movement might think,” he said. “Instagram is more effective than people realize — it can sometimes be clear just from Instagram profiles what these individuals feel, and how they relate to the movement.”

- Be cautious about focusing on individuals. “I don’t often write about specific individuals on the far right because I worry that it gives them a platform they can benefit from,” he said. “But sometimes you can.”

- Collaborate to geolocate social media images. Last year, Colborne was able to locate a leader of America’s far-right Rise Above Movement by sharing his social media images with OSINT experts at Bellingcat. Using unique rock formations in one image, they were able to locate the man to a particular spot in Serbia. Colborne then used local company registry records to show that the man — under intense legal scrutiny in the US — was attempting to set up a new base in Serbia.

Additional Reading

How Open Source Experts Identified the US Capitol Rioters

My Favorite Tools with BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman

The Forensic Methods Reporters Are Using to Reveal Attacks by Security Forces

This article was originally published by the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN). It was republished on IJNet with permission.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via little plant.