Before heading to Bangladesh in January, I studied reports on the challenges local journalists face. Terrorism was high on the list.

During meetings in the sprawling capital of Dhaka, a question often was raised: How do we cover the rise of Islamic extremism in our own backyard? Their concerns had a familiar ring.

What are the do’s and don’ts of reporting on terrorism and militancy? Are there any guidelines that can help? What are the hazards of dealing with groups that espouse violence to achieve their goals?

The journalists described escalating attacks against the press. A veteran reporter was disabled for five months after a vicious beating by extremists. Several others told of threats and intimidation. One still was wearing a cast on his arm from an assault.

On Feb. 2, Abdul Hakim Shimul, a correspondent for the daily Samakal newspaper, was shot in the head and face while covering political unrest. He died a day later. Journalists speculated: Was he targeted or caught in crossfire when shooting started?

“Bangladesh has become a dangerous place for anyone who dares to cross an invisible line set by Islamic extremists intent on silencing dissenting voices with knives and guns,” CNN reported in April 2016. Many journalists still take the risk.

For months, Dhaka Tribune reporter Adil Sakhawat courted sources in the hope they would lead him to a militant group responsible for the October 2016 attack that killed nine guards along the Myanmar-Bangladesh border.

Finally, he got the green light. Driven by motorcycle to a remote spot, he was searched and blindfolded. A two-hour hike through the jungle led him to the group’s second-in-command.

The reporter learned that border guards were targeted in order to “loot their arms and ammunition for our guerrilla training.” The group’s motive, the leader said, was to protect Rohingyas, an oppressed Muslim minority in Myanmar.

The story ran on Jan. 11 with the headline, “We will fight until the last drop of blood.”

Why did Sakhawat, 28, married, with two children, take the risk? “Militancy and radicalization are main concerns around the world. We have to cover not just the leaders, but the roots of these groups, their followers and their motives,” the denim-clad reporter said. “I trusted my sources.”

The resources on covering terrorism I gathered for Bangladesh are applicable anywhere in the world. Here are three that can be helpful in planning reporting strategies:

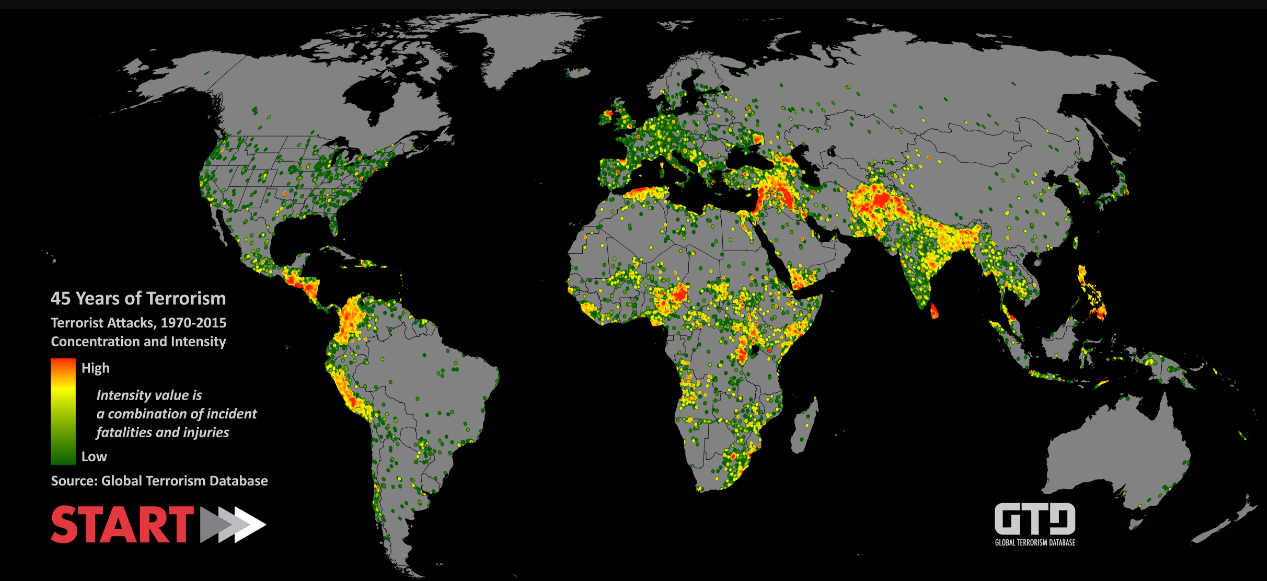

The University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database (GTD) offers one-stop shopping for researching terror attacks. According to its website, the list of more than 150,000 incidents is the world’s most comprehensive unclassified database on terrorist events.

For each one, there is date and location, weapons used and nature of the target, the number of casualties and — when identifiable — the group or individual responsible. GTD operates as part of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START).

“GTD has gotten a lot of media traffic in recent years – millions of pageviews per month,” says START director Gary LaFree. On the afternoon we talked, he fielded a call from The Wall Street Journal seeking information about the seven predominantly Muslim countries — Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Somalia, Libya, Iran and Sudan — named in President Trump’s travel ban.

LaFree noted that GTD’s database shows that there is not a single case of a terrorist attack involving a perpetrator from one of the seven countries where an American has been killed on U.S. soil.

Another user-friendly source: “Handbook on Reporting Terrorism,” funded by International Media Support, Denmark. On the list of do’s and don’ts:

Provide context and don’t oversimplify. Such events don’t happen in a vacuum.

Don’t speculate on anything! Deal in facts only and what is known and can be verified.

What we report should not jeopardize human life and in many of these cases we need to cooperate with security forces/government officials to avoid putting others in harm’s way.

Don’t use panicky and sensational headlines

Don’t use inflammatory, inappropriate or derogatory words

Ensure your story includes input from multiple sources.

Promote social cohesion, peace and patriotism without being the voice or mouthpiece of any actor/agent

Tell stories about communities’ resilience, good intervention and other positive angles.

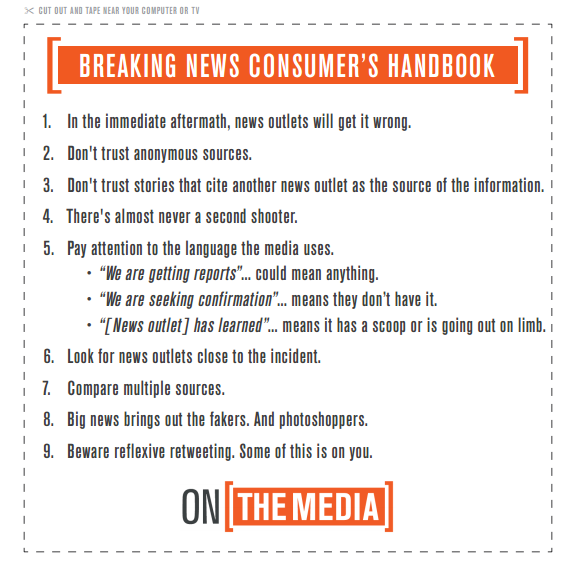

The “Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook,” by Alex Goldman, offers advice to journalists driven by 24/7 deadlines and competition.

“Rushing out unconfirmed or early information or social media rumors is risky. The information can be inaccurate or foster myths about who is responsible for the violence,” writes Goldman, a producer for On the Media.

Among guidelines from the handbook’s terrorism edition:

For safety tips, journalists should check Committee to Protect Journalists, International News Safety Institute, Reporters without Borders and Rory Peck Trust, which provides materials to help reporters assess danger.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via DVIDSHUB. Second image courtesy of the Global Terrorism Database. Third image courtesy of On the Media.