In its two years of existence, Peruvian news site OjoPúblico has earned a well-deserved prestige in the Latin American media landscape by combining investigative journalism, innovation, good writing and an overall quality that has not gone unnoticed by international organizations and colleagues. In 2015, OjoPúblico won the Best Investigation of the Year award in the Small Newsroom category of the Data Journalism Awards for its Sworn Accounts application, which allowed users to analyze the evolution of the wealth of dozens of Lima’s mayors ahead of the municipal elections.

OjoPúblico was also one of the media outlets working with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists to report on the largest massive data leak so far: the Panama Papers. The site features a special section revealing the links between the Panamanian law firm Mossak Fonseca and Peru's political and corporate power.

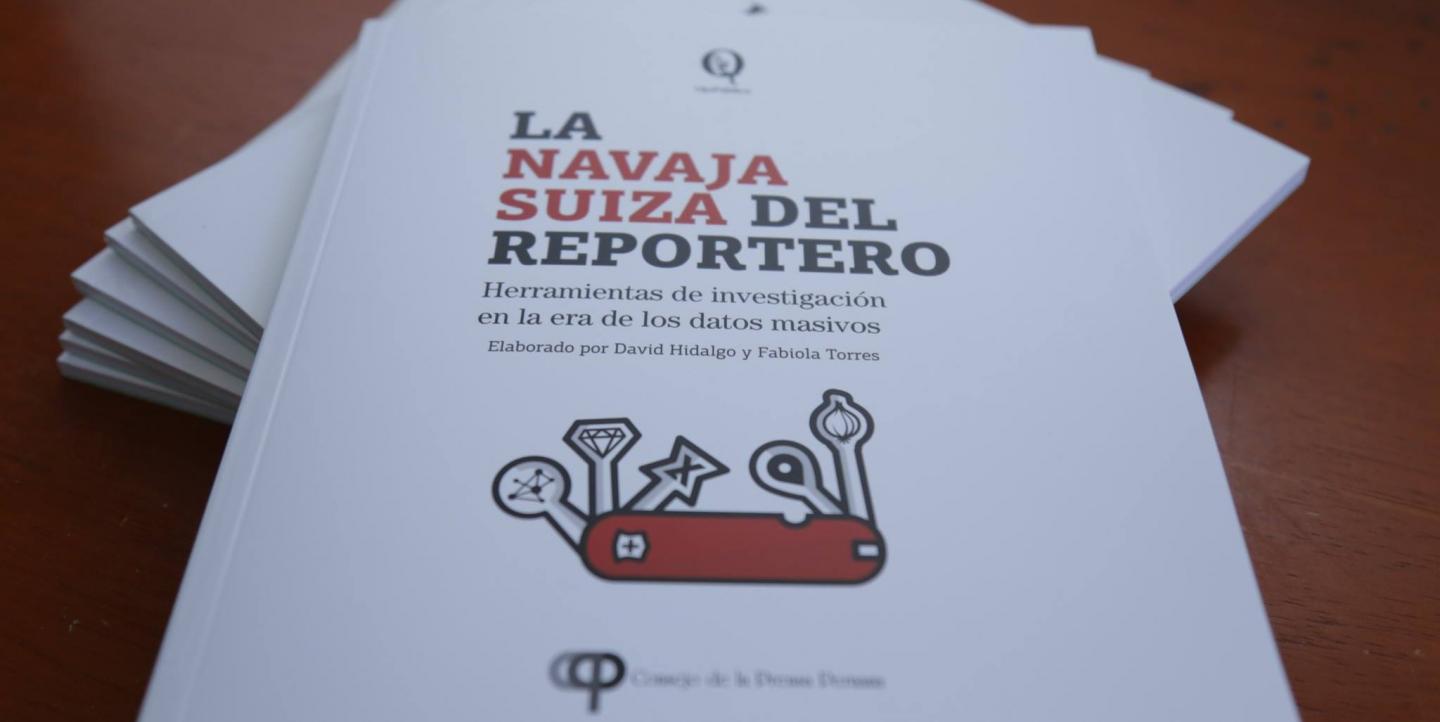

And now, with the aim of contributing to the promotion of data-based investigations and asserting its vision of journalism as an essential service to democracy, OjoPúblico has published “La navaja suiza del reportero. Herramientas de investigación en la era de los datos masivos” (“The Swiss Army Knife Journalist: Digital Research Tools in the Era of Big Data”), a resource for Hispanic reporters who want to become familiar with the world of data journalism and, above all, to understand its meaning and relevance in Latin America and the world.

The book, backed by the Peruvian Press Council and supported by Hivos Foundation and IDEA Internacional, is being launched today and will be available in print and PDF. It is divided into three parts: “The new alphabet of journalists: How a hacker accelerated the reinvention of journalism”; “How to trace crimes in a database? Twenty investigations that changed the way journalism is done” and “The path to a culture of innovation: Digital investigative journalism labs in Peru."

IJNet talked to authors David Hidalgo, OjoPúblico’s director, and Fabiola Torres, data editor.

IJNet: What gap do you intend to fill and how do you expect reporters to use The Swiss Army Knife Journalist?

In 2014, 19 Latin American countries already had access to information laws or statutes. With the investigations these laws allow, do you think the trend will always be toward more access, or that it will increasingly become a territory of dispute?

We can infer the answer based on the Peruvian experience. Despite the transparency laws and the Open Government official initiative, public institutions apply restrictive measures to access information, as is the case of politicians' affidavits. Civil society and journalists are in an ongoing effort to make the state understand the need for open data as a foundation of democratic life. The strategies of various governments, especially in societies such as Latin America, still tend to restrict access, sometimes with delusional arguments — like when Costa Rican authorities delivered their information with a password so journalists would receive it, but could not use it. Their argument was, basically, that they had no obligation to make things easier.

What do you think are the major resistances of Latin American journalism schools and traditional media to enter the world of data?

The main challenge is that we actually do not understand the meaning of data journalism. Some take it as a new and revolutionary specialty and others as a simple variation of the tools available. It’s not one or the other. What we need to understand is that we are at a unique moment in history in which journalism can approach reality in ways that, until recently, were completely unknown. It’s not about learning how to use digital tools, but about thinking differently about the same problems. It’s about building new ways of questioning, new ways of raising hypothesis and new working methods. It is not a question of scale, but a new type of intuition to pursue the truth.

There are colleagues for whom words like "data" or "scraping" sound strange, difficult and involving abilities they believe are beyond their reach. How can we bring data journalism and digital tools to someone who received their training 10 or 15 years ago?

The way we did: by trial and error. The only difference is that the members of our team have a tremendous voracity to try everything, to discover, create, innovate. We're like a kid who received a PlayStation 10 years before it went on the market. From the beginning, we felt that we were changing when our language changed. Now we know that a news team of the 21st century is a task force that includes developers and reporters in a technological environment. Our recommendation is to take the decision to engage in a culture of innovation and, as indicated by the historical fundamentals of journalism, ask all the time.

Main image courtesy of OjoPúblico.

Secondary image: Fabiola Torres and David Hidalgo. Photo by Audrey Cordova.