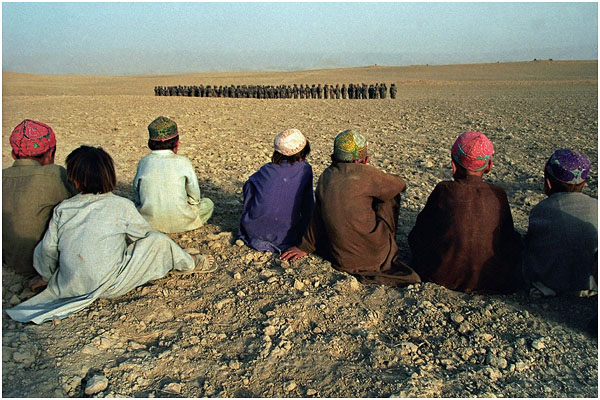

Two-time World Press Photo winner Sergey Maximishin tells IJNet what he thinks about citizen journalism, the role of post-production and how bad photos can sometimes lead to great ones.

Maximishin teaches photojournalism at the School of Modern Photography Photoplay in Moscow and Zekh Photography School in St. Petersburg. His photos have appeared in Time, Newsweek, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Stern and BusinessWeek.

IJNet: Where do you find your stories?

Sergey Maximishin: How do I find stories? I am always looking for them. I read the web, talk to people. I often look at amateur photos, because bad photos often lead to good ideas. There is no better way to meet people than to approach them and say: "Hello, my name is Sergey. I am a journalist." That’s my only way.

IJNet: What’s the story behind the "Tea Break" photo?

SM: At first, I thought I was doing a story about a theater where the actors had Down Syndrome. Then I shifted the accent a little -- I noticed that the two actors from the studio, Yasha and Masha, were affectionate toward each other, and I asked Yasha whether he loved Masha and he said "yes." Then I asked Masha if she loved Yasha and she said “yes.” So I shot a love story.

This photo is one of a series taken at the Psychoneurological Institution no. 7. It became famous because it won the World Press Photo competition. It's like a frame from a film.

IJNet: Do you manipulate your images?

SM: Of course, any photographic image requires some post-production. Another thing is that a photojournalist has very rigid boundaries of what he can and cannot do with an image. I can add a little more contrast to an image, crop it slightly, dust it off, but I cannot intrude on the informational component.

IJNet: What distinguishes a photojournalist from a citizen reporter?

SM: Sometimes there is more truth in their pictures than those of professional photojournalists. A professional journalist always knows what is expected. A blogger is like a mirror; what he shoots reflects everything that gets into it. Citizen journalists can often shoot something that cannot be shot by a professional journalist. We would never have seen what was happening at Abu Ghraib prison or Saddam's execution if it were not for people with mobile phones who were there.

But there are things that citizen journalists would never do – an aftermath story, for example. They will not return in half a year to an earthquake site to see what happened there since and how people live, because it requires special journalistic skills. That’s why citizen journalists do not interfere with the work of news journalists. But thanks to them, often we find out the truth only because a person with a mobile phone happened to be in a certain place at a certain time.

This is the first part of a two-part interview with Maximishin.

All photos copyright Sergey Maximishin