This is part one of a two-part series on combating biases in Generative AI. The second part can be found here.

“You don’t need a PhD from MIT to make a difference in the fight for algorithmic justice.

All you need is a curious mind and a human heart.”

Joy Buolamwini, PhD, “Unmasking AI”

In 2023, English-language global media quoted five male figures in artificial intelligence (AI) – Elon Musk, Sam Altman, Geoffrey Hinton, Jensen Huang and Greg Brockman – eight times more frequently than all 42 women AI experts highlighted in Time Magazine’s top 100 list of AI influencers, which includes names like Grimes, Margrethe Vestager, Timnit Gebru, Margaret Mitchell, Emily Bender and Joy Buolamwini.

This gender bias, uncovered by AKAS’ analysis of 5 million online news articles in 2023 that reference AI on GDELT global online news database, has flown under journalism’s radar. Mitigating gender bias in discussions around AI is an important way to ensure that news reflects the diversity of our world, and is relevant to as wide an audience as possible.

I spoke with several experts about biases in generative AI, including gender bias, and the role of journalism in breaking these biases.

The three man-made biases created by generative AI

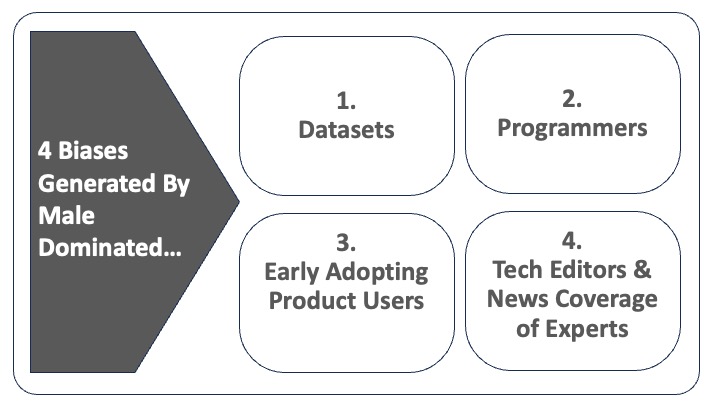

The existence of biases baked into generative AI (GenAI) – which includes ChatGPT, Google’s Bard, and image generators like Midjourney – quiets, distorts, and silences if not outright erases the voices of certain underrepresented groups. This is because generative AI amplifies societal biases through the datasets it uses in algorithms to generate text, images and video that use an unrepresentative small group as a default for the whole global population.

Programmers’ own perspectives of the world also inform the algorithms they develop, adding further bias to generated content. For example, facial recognition technology, used in policing, is disproportionately based on data from white (80%) and male (75%) faces. While the accuracy is 99-100% in detecting white male faces, it falls sharply to 65% for black women. Similarly, GenAI-assisted news articles are heavily reliant on a historical pool of articles in which men’s share of contributor/protagonist voices is multiple times higher than that of women.

Algorithms created with these biases become what Joy Buolamwini refers to in her new book, Unmasking AI, as “the coded gaze” (i.e. the priorities, preferences and even the prejudices of coders reflected in the products they have shaped). The groups who are underrepresented become “the excoded” (i.e. individuals or communities that are harmed by algorithmic systems). The “coded gaze” deepens biases that exist in the datasets.

A third layer of bias comes from product users, for instance the early adopters of GenAI text generators like ChatGPT or image generators like Midjourney, DALL-E and Stable Diffusion. In the words of Octavia Sheepshanks, journalist and AI researcher, “What often doesn’t get mentioned is the fact that it’s the people using the images that have also shaped the image generator models.”

These early product users further shape the AI-generated content through the way in which they interact with the products, with their own biases being fed back to the self-learning algorithms.

Global-Northern-white-male dominated perspectives

What do these datasets, programmers and product users all have in common? They are overwhelmingly more likely to represent the perspectives, values and tastes of English-speaking white men from cultures in the northern hemisphere.

In an August 2023 content analysis of ChatGPT, which explores how gender and race influences the portrayal of CEOs in ChatGPT’s content, Kalev Leetaru, founder of the GDELT Project, concluded that “the end result raises existential gender and racial bias questions” about large language models (LLMs).

For example, while ChatGPT had described successful white male CEOS in terms of their skills, successful female CEOs and CEOs of color were described in terms of their identity and ability to fight adversity, rather than their competency-based skillset.

Libertarian views that value defending freedom of expression and protecting innovation online over interventionism pervade Big Tech and engineering schools. They present a roadblock to addressing bias in AI.

Hany Farid, a computer science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, worries that these views mask ethical ignorance at best, or an underlying apathy and lack of care on the part of the AI sector at worst. They represent, he argues, “a dangerous way to look at the world, especially when you focus on the harms that have been done to women, children, and under-represented groups, societies and democracies.”

Journalism adds a fourth impediment to tackling the problem of GenAI bias

There is a danger that journalists are also helping write women and other underrepresented groups out of the future of AI. Currently, only a small minority of tech news editors in the U.S. (18%) and the U.K. (23%) are women. Furthermore, in AI news coverage women are featured as experts, contributors or protagonists four times less frequently than men, according to our GDELT analysis.

When we overlay the race dimension onto gender, the problem is compounded in several ways. Firstly, women of color are significantly more likely than men or white women to be left out of editorial decision-making and as contributors to stories. Secondly, when they are interviewed, women of color are much more likely to be asked questions based on their identity rather than their expertise.

Agnes Stenbom, head of IN/LAB in Schibsted, Sweden warns that news organizations must be mindful of their use of gendered language – for example, not assuming that doctors are men and nurses women – as this can “further cement” gendered biases.

Lars Damgaard Nielsen, CEO and co-founder of Denmark’s MediaCatch, warns that women of color are especially underrepresented in the news in Denmark. This is reflected in how people of color are portrayed in the news, according to an analysis last year using MediaCatch’s AI-based tool DiversityCatch, which showed that “non-Western individuals are often not there because of their professional expertise, but because of their identity.”

Journalism must act as a watchdog for GenAI technology to mitigate existing biases

The most effective way to mitigate homogeneity-related biases is to create more inclusive datasets, as Buolamwini argues in her book. However, regulators and journalists face a significant challenge that they should push back against – they do not know the exact data that AI draws from due to the AI industry’s lack of transparency.

“Transparency is becoming more and more limited. As profit has entered into the equation, companies have become more proprietary with their models and less willing to share,” argued Jessica Kuntz, policy director at Pitt Cyber. This absence of transparency prevents algorithmic audits, making it difficult for journalists to build guardrails to protect against biases.

If the GenAI space is left to develop unchallenged, as Big Tech currently stipulates, a future AI-rich world will find itself increasingly lacking a diversity of perspectives, such as those of women, ethnic minorities, publics from the global south and other cultures.

In a follow-up article, I’ll explore two sets of solutions for newsrooms to mitigate the dominance of male voices in GenAI news coverage.

Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on Unsplash.