Indigenous communities are often underrepresented in news coverage, and on the stories they do cover, reporters can struggle to provide accurate reporting.

In an effort to address this, the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication (UO SOJC) and the university’s Many Nations Longhouse convened a panel of journalists to discuss reporting in Indigenous communities.

Based on that discussion, and further research, below are eight ways non-Native journalists can accurately and effectively report on Indigenous communities.

(1) Understand the past, as well as the present

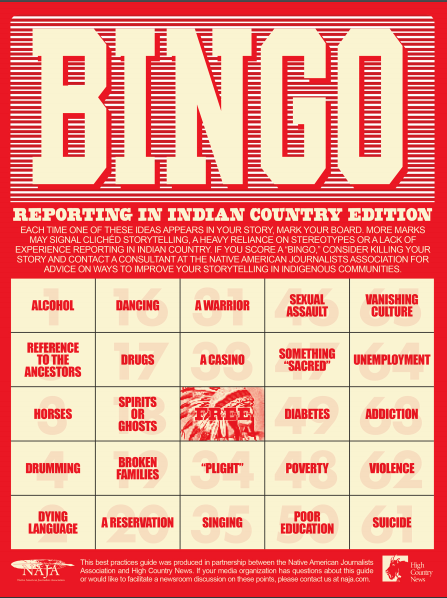

Local and national reporters alike should review previous coverage to identify overused narratives or misreported topics. Stereotypical historical portrayals and other inaccurate representations of Indigenous people negatively impact these communities. They also perpetuate harmful journalistic practices.

In 2017, a member of the Nipissing First Nation found thousands of stories with racist and stereotypical media portrayals of Indigenous people in the Toronto Star archives.

Identifying coverage gaps or negative experiences that might have caused a problem between reporters and members of a community is critical, as these experiences could impact future reporting and relationship building.

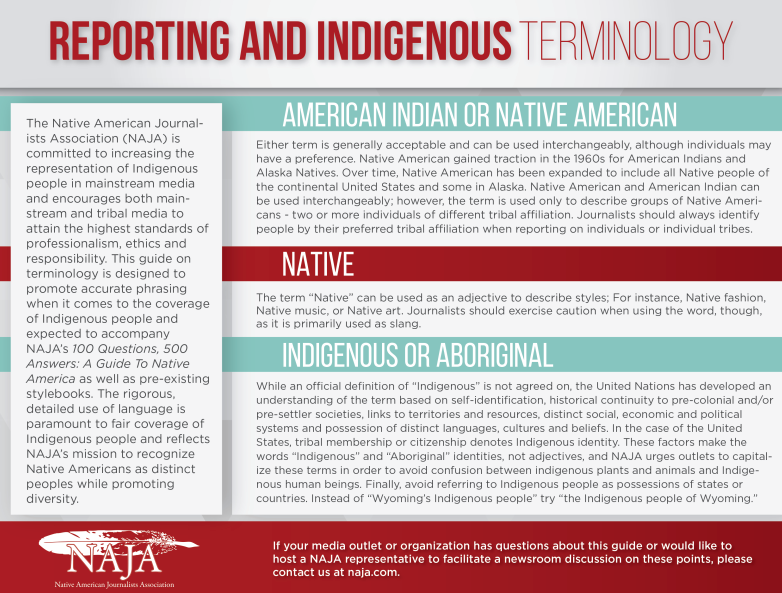

To help prevent this, journalists should explore resources from the Native American Journalists Association (NAJA), Indigenous Reporting and the International Journalists’ Network to help journalists create fair, accurate and effective coverage of Indigenous communities. These platforms also provide resources for finding experts, AP style guides and specialized tips for reporting based on story content.

(2) Check your ego, as well as your sources

“Just because it’s new to you, doesn’t mean it’s a new story,” said High Country News assistant editor and SOJC alum, Anna Smith.

There may seem like an obvious arc for a story, but too often this results in furthering negative stereotypes, coverage gaps, and engendering distrust between Indigenous communities and journalists.

Journalists need to take action and do things differently, such as seeking out Indigenous sources to fill coverage gaps. Indigenous people made up only 0.6% of people portrayed in stories in the top 20 internet news sites by traffic, as discussed in this Nieman Report.

The report also addresses how editors are often hesitant to give reporters stories focused on Indigenous communities for fear of portraying the over-told poverty, disease or alcoholism narratives. Journalists should dig deeper and look at the real issues and injustices these communities are facing, not just the assumed narratives.

Tristan Ahtone, High Country News’ associate editor for Indigenous Affairs, president of NAJA and a member of the Kiowa Tribe cautions about creating predetermined narratives for stories. Just because a reporter thinks they know the story, doesn't mean it’s the right one.

“Sometimes someone will tell you there is something better, and you need to listen,” he said.

As with any story, journalists covering Indigenous communities should double-check their sources for legitimacy. Making sure a quoted expert is actually from the community, and is not furthering inaccurate information, is arguably even more important in this space.

(3) Do a self-assessment and ask for help

Covering Indigenous communities takes a lot of work and careful judgment. While many journalists may feel confident that they’re objective in their reporting, and careful to respect sources, it’s important to identify implicit biases that you may not even realize you have.

As journalists choose sources, and research and discuss stories with their colleagues, they can become influenced by implicit biases and prejudices, according to a recent Nieman Reports study.

Recognizing potentially harmful reporting techniques — such as how journalists take notes, observe cultural events or talk to sources — and redefining those reporting routines into more respectful practices can help all journalists to do their job better. In doing this, journalists need to forget what they think they know, and actively listen to — and observe — their sources.

Journalists should also consider reaching out to sources and other members of Indigenous communities to ask for help ensuring accuracy in their work.

(4) Invest more time than you think you need

Deadlines put pressure on journalists to get information quickly. However, being flexible and allocating more time for interviews, especially with under-reported communities, is important. Journalists need to make time to connect with their sources, and to understand issues that are often complex.

“Get to know us,” said Rebecca Tallent, a member of the Cherokee Nation and University of Idaho associate professor emeritus. “Do not just parachute into a tribe to do a story and leave.”

KLCC reporter Melorie Begay also noted that Indigenous people may have a different understanding and concept of time. Understanding and respecting this is one of the most important things when building relationships with sources from Indigenous communities.

“These are people who have never been given the opportunity to talk about their lives,” said Begay. “Take the time to listen.”

(5) Learn from your peers

No matter how much research or previous reporting a non-Native journalist has conducted on Indigenous communities, there is still a chance to get it wrong.

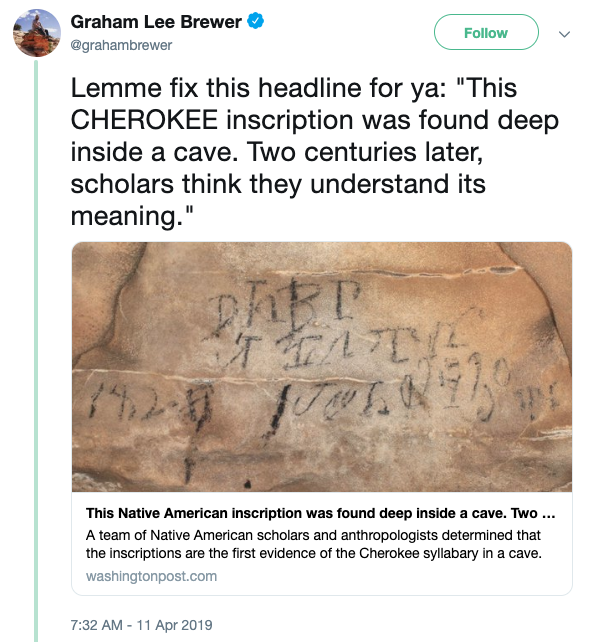

One way to avoid this is to learn from Native journalists. Begay recommended following Indigenous reporters on social media.

“Read their work and watch their comments,” she said. “They comment on stories that are bad or wrong. It’s a good way to check if you’re falling into the same negative areas of reporting.”

(6) Recognize diversity

Journalists should actively name tribal nations instead of using blanket terms like “Native American.” Every nation is different, and journalists need to actively appreciate the differences between Indigenous communities.

Tallent said it is incredibly important to use the names of the people being interviewed, and to ask how they would like to be referred to in the story. Doing this is simple, but important, and she argues that it will help to humanize people and nations.

“We are not children, mascots, mystical or history,” Tallent said. “We are real people here, and literally in your backyard.”

(7) Build relationships within Indigenous communities

Journalists need to be hyper-aware of their surroundings and respect the cultural protocols that each individual community might have.

Media organizations have their own role to play, especially in local communities. Instead of relying on resources from national organizations like NAJA, they can reach out to the Indigenous communities they regularly cover, and work with them to develop a set of reporting guidelines and protocols for each individual tribe and nation.

“We have been lied to and mistreated for generations,” Tallent said. “Do not expect us to welcome you with open arms. You need to do some active work.”

Journalists are there to report on and for these communities — not to open a window into them, said Ahtone and Smith.

“They want to know you’re not going to rush into their history and create a snapshot,” said KLCC reporter and member of the Nez Perce Tribe Brian Bull said access to these communities starts with respect.

As journalists, it’s important to recognize that Indigenous communities are not just groups of people to be reported on like they’re exhibits. While including these communities in coverage, it’s important to recognize that they are part of the audience, and journalists’ reporting should appeal to them as well.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Etienne Boulanger.

Destiny Alvarez is a journalist based in Portland, Oregon. She graduated from the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC) with a Master’s in Journalism in 2019 and from the University of Idaho with a B.S in Journalism in 2017. Alvarez was the 2019 Editor-in-Chief of the award-winning student-led SOJC publication Flux Magazine. Alvarez served as the Spring 2019 Demystifying Media Intern and the 2019 Charles Snowden Program for Excellence in Journalism intern for The Register-Guard in Eugene, Oregon. She is a happy plant mom, journalist and coffee enthusiast.

This article was reported with help from Damian Radcliffe, the Carolyn S. Chambers Professor in Journalism, and a Professor of Practice, at the University of Oregon. He is also a Fellow of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, an Honorary Research Fellow at Cardiff University’s School of Journalism, Media and Culture Studies, and a fellow of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA).