The spread of mobile phones and connectivity across Africa offers opportunities and challenges for the way citizens discover and use information. If people have the skills and knowledge to harness them, open data and new technologies hold the keys to the media’s future.

Code for Africa is the continent’s largest network of civic technology and open data labs. We work with media partners to create actionable information for citizens that helps them in their daily lives. From checking if their doctor is dodgy to seeing if they are registered to vote, Code for Africa’s tools have been used in dozens of countries to help empower people.

How might technology be used in the coming years to further democratize the use of information and news across Africa? Our experts from Kenya and Nigeria set out their predictions:

Media freedoms in Kenya

Media freedoms in Kenya

by Catherine Gicheru, ICFJ Knight Fellow at Code for Kenya

Computers, the internet and mobile phones continue to change the way the world works, plays and communicates. In Kenya, there has been an exponential growth in ownership of mobile phones, reaching 88.1 percent penetration in September 2015. With 21.6 million internet subscriptions, about 74.2 percent of Kenyans now have access to internet services.

The advance of new media and technology has changed the way journalists work as well as how information is obtained and produced. The business of news is more of a dialogue between news providers and receivers of information. Citizens have much greater control over how and when they receive information. Audience involvement, either through cellphones or social media, has fostered a culture where more people value press freedom more broadly.

These technologies have also introduced new threats to media freedom. Mobile companies are obliged to give up cellphone records when ordered by the courts, presenting journalists with the challenge of keeping their sources secret. The Security Laws Amendment Act 2014 safeguards and widens the powers of police and undefined ‘national security organs’ to surveil and intercept communications, restricting media freedom. It also restricts citizens’ ability to point out and demand action on government failures. That is where whistleblowing platforms like Code for Africa’s AfriLEAKS come into play, as they provide citizens and journalists alike a platform where they can share information on stories and tips.

Digital technologies have provided journalists with opportunities to be innovative, ethical and inclusive, and to collaborate to solve problems and improve people’s lives. An example is GotToVote, which not only provides citizens with information on elections which was previously not easily accessible, but also gives journalists information that adds nuance and depth to their reporting. These tools will become even more crucial in the future, as not many journalists have the skills to analyze, synthesize and interpret the vast array of statistical information being made available on the internet.

Fighting for good healthcare in Nigeria

Fighting for good healthcare in Nigeria

by Temi Adeoye, ICFJ Knight Fellow at Code for Nigeria

The desperate need for affordable healthcare in Nigeria’s poorly funded, understaffed health sector has driven many — especially the poor and vulnerable — into the hands of persons not qualified to treat them. Quacks. The impact of quackery is very difficult to measure, but nonetheless extremely severe. Its cost is measured in human terms — agonizing disillusionment, temporary or permanent deformation, complication of existing ailments and, in some cases, needless deaths.

Public medical institutions are not insulated from this cancer. The complicity and culpable negligence of recruiters at public health service commissions paves the way for quacks to infiltrate the system. It is a major headache for health regulatory authorities in Nigeria. The MDCN has over 40 cases against accused quacks in several courts across the country, but convictions are rare.

Code for Nigeria has therefore partnered with West Africa’s largest online news outfit, Sahara Reporters, to deploy a data-driven tool called Dodgy Doctors to empower citizens to fight quackery from the comfort of their computers and mobiles.

Dodgy Doctors is one of a set of tools in the SaharaHealth initiative that uses official MDCN data to help citizens quickly and easily check whether their doctor is properly registered. All they need to do is type a doctor’s name and the service cross-checks it with the MDCN’s master register.

Other apps in the suite include Hospital Finder and Medicine Prices. Hospital Finder is a geo-located service that helps citizens reduce the critical time it takes to locate health facilities around them. Medicine Prices helps citizens check how much the government expects them to pay for medicines.

Data-driven tools like SaharaHealth are changing how media affects our lives. It is no longer sufficient to talk about what is wrong in our world: the media should give citizens simple, actionable and easy-to-use tools to solve their own problems.

This article is an adaptation of a piece that originally appeared in the African Free Press, a Media Institute of Southern Africa project, published to mark the 25th anniversary of the adoption of the Windhoek Declaration. It was originally published at whk25.misa.org under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license and is republished on IJNet with permission.

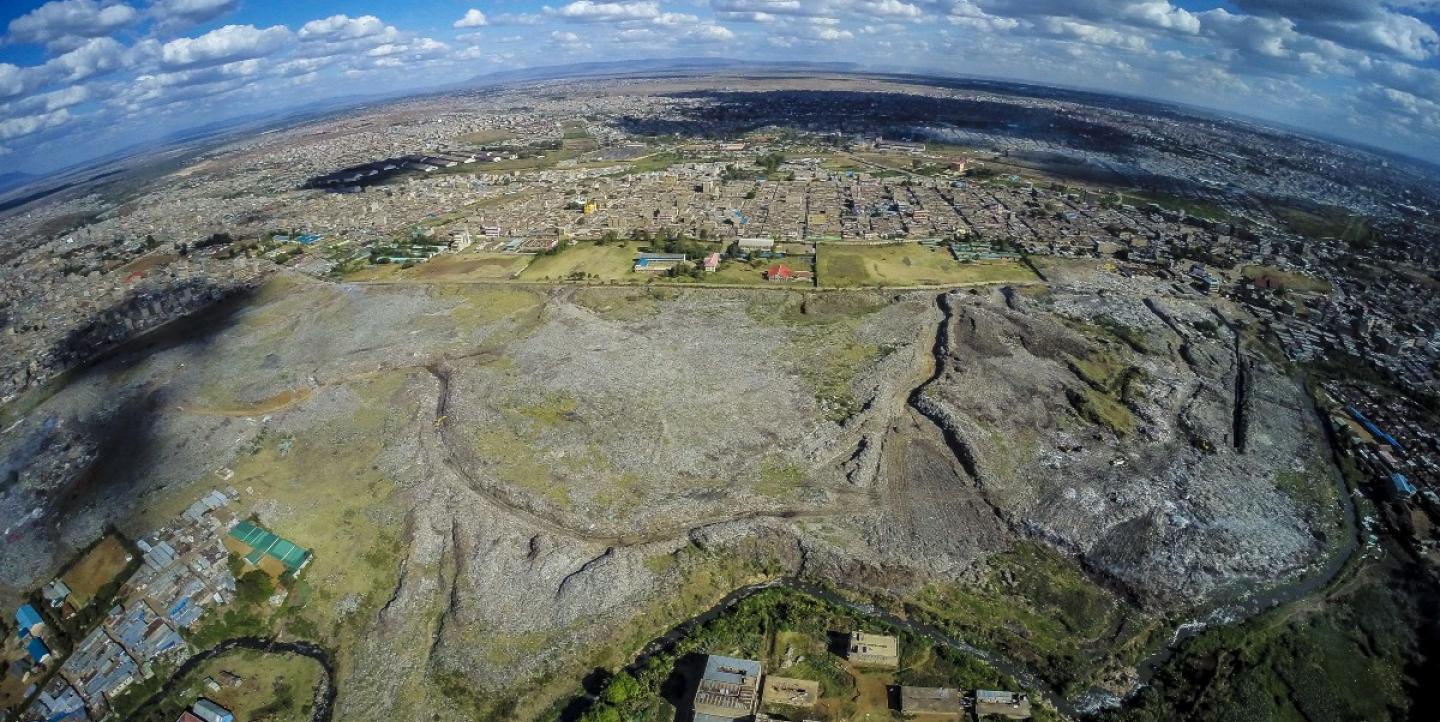

Main image courtesy of African skyCAM.