Johnny Miller is a Code for Africa News Fellow who specializes in drone photography and reporting. Here, he shares his top six pieces of advice for crafting effective drone shots to complement your storytelling:

1. Film something you can’t film from the ground.

The cardinal sin of drone journalism is flying when unnecessary. Drones are annoying, they’re expensive, and risky. Why would you want to fly when you don’t have to? There are plenty of other options that you should attempt to use first — satellite images, Google Earth, even standing on tall buildings or on hills.

But there are legitimate reasons to use a drone, and these are the key to using the drone as a tool, and not just a gimmick. Think immediacy and access — is the thing you’re trying to film happening now? If an image is not available on satellite imagery, drones may be the only way to see it. Ditto for flat terrain, and anywhere with restricted ground access.

2. Know the laws.

Most countries now have some version of laws regarding drone use on their books, and it’s imperative to know the law before you fly. Here is a partial list of worldwide drone laws. General guidelines are: Do not fly over buildings, roads, or people; stay below 400ft altitude, and stay well away from airports, helipads, and sensitive installations. There may also be special regulations depending on what you want to do with the footage — commercial operations (flying for money) is different than flying for fun. How you will be operating as a journalist is probably a gray area between the two…so be as careful and as knowledgeable as you can!

Flying in wide open areas like a dam are safe, and usually legal. ©Johnny Miller / Code For Africa

3. Map where you’re going to fly before you get there.

Just like flying an airplane, its important to create a flight plan before you send the drone up into the air. You don’t have to use anything too fancy: Google Earth is an excellent resource to see elevation, terrain, roads and buildings. Knowing where you will take off and land from, as well as secondary landing zones in case of emergencies, is also important.

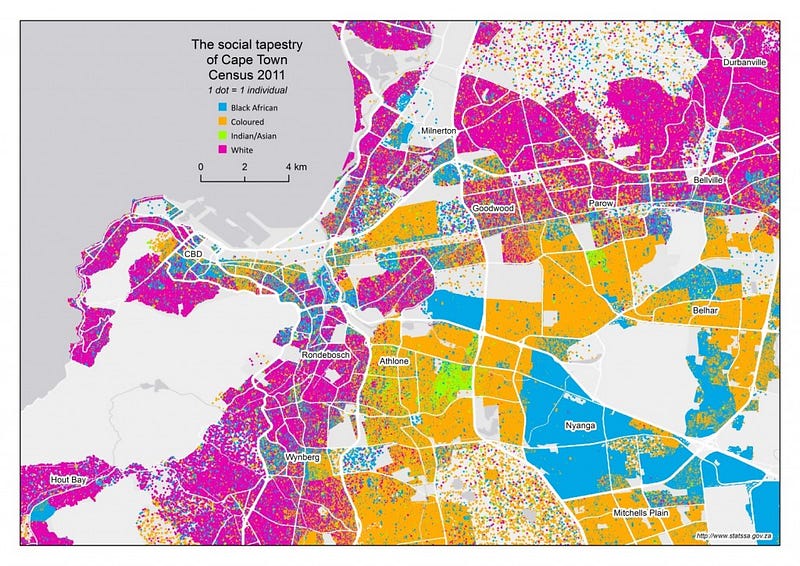

You can also use a variety of mapping data to plan what you want to look at with the drone. Depending on your location, there may be maps that show environmental data, census data, or previous survey data to help you plan your flights. You may find that it’s easier (and cheaper) to just use satellite imagery that’s already been created!

4. Long, steady shots work better.

The easiest way to tell if someone is an experienced drone pilot is by looking at the length of the steady shots they take in their video. Aerial videography is exciting, interesting, and can contain a lot of visual information. You want to give your viewers the longest possible time to absorb that information before making a cut, or adjusting the direction of the drone. So when you hold a shot, don’t touch the yaw! The yaw turns the drone from side to side, and will immediately ruin a long tracking shot. If you find yourself drifting slightly off course, continue to hold the shot as-is, and then come back and repeat it. You might find the original, “off-center” shot works better!

Generally you are looking at reveals, pushes, tracking, and point-of-interest style shots. These four types of shots will be your bread-and-butter, and its important that you practice them again and again in a controlled environment, before you take the drone out into the field.

5. Your footage won’t stand alone.

Drones are an incredible tool for a journalist, but they RARELY can tell the whole story. You will inevitably be creating additional resources to build a great story, including written work, stills and video from the ground, and data visualizations. Don’t oversell your ability to tell a story only from the air. Package the drone concept to your editor as a valuable tool that can give your viewers a new perspective, but one that works best as an adjunct to your original skill set. Tools like Shorthand can create amazing, immersive storytelling like this.

6. Know when to say no.

Drones are dangerous, and can be ethically ambiguous. There is not a good set of precedents for how drones and drone footage can be legally used, which means operating them sometimes falls into a gray area. Use your intuition. Think of how you would react if you were witnessing someone else flying the drone in the same way. And crucially, don’t be bullied by someone who is overselling the drone as a gimmick, or wanting you to use it in unsafe conditions. Remember to only use the drone as a last resort — using satellite images or taking photos from the ground is a much safer option. And finally, know that legally, the operator (You!) is the one responsible for anything that goes wrong…not your editor.

For more information on great drone journalism check out the Slumscapes package by Thomson Reuters Foundation here.

Johnny Miller is a Code for Africa News Fellow who specializes in drone photography and reporting. This article first appeared on his Medium page and is republished with permission.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via Peter Linehan.